[Summer 2007]

by Henry Lehmann

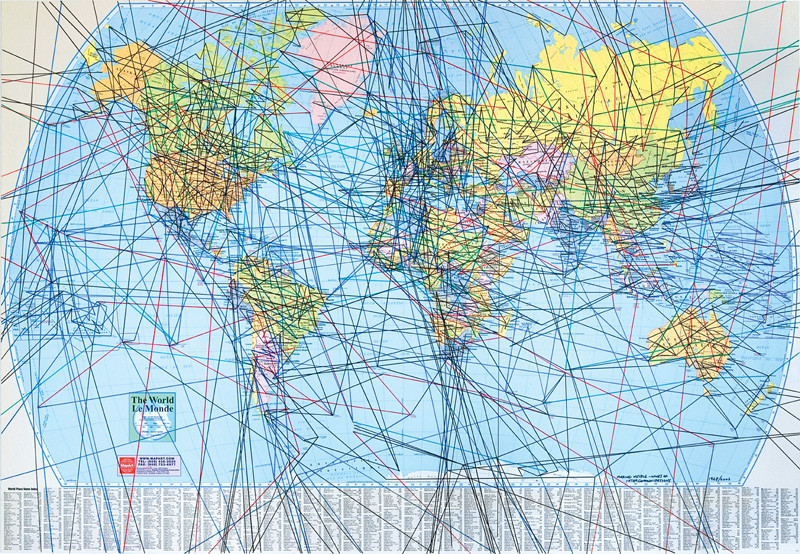

The title was as brief and streamlined as the piece itself, called simply Worldline. With this unearthly 1971 project, based on the ultimate invisibility of pure line and on its infinite conceptual reach, Montreal artist Bill Vazan truly launched his career.

Of course, most of this line, tangibly linked up at assorted art spaces around the world, had to be imagined, but so do other lines, such as the equator and longitudinal grids. Certainly, Worldline, with its economics of means to put all of NASA to shame, sets out in no unclear terms the thrust of Vazan’s entire career. It was just a matter of time before the notion of line and the points from which it is theoretically constructed would begin, in Vazan’s hands, to metamorphose, and to assume metaphorical dimensions.

Vazan’s essential approach, like that of countless cutting-edge artists in the late 1960s and 1970s, played on dramatic counterpointing or dovetailing of the tangible and intangible. What came to distinguish Vazan from other land art practitioners was the intensity of his obsession and the unceasing persistence with which he revisited and revised his conceptual geography (activities that he pursues to the present day). However, he never subjects it to division; instead, he multiplies and expands it to attain cosmic proportions, in which even our planet seems a tad shrunken and small.

If one of Vazan’s preoccupations has been with invisibility and logical certainty – we trust that his world line is precisely that – another focus has been on physical reality that is not altogether a function of belief, knowledge, or pure theoretical geometry and cartography. For all its majestic vastness, Worldline consisted in fact of no more – or less – than sequences of Platonic dots and an almost aesthetic flourish of pencil markings and elements of collage from the other art spaces around the world participating in the overall project.

But Vazan’s best-known “medium,” his all-time trademark, are small boulders, the artist’s preferred “objets-trouvés”, theoretical geometric points so swollen and overgrown that they go from the infinitely tiny to ponderous, time-stopping physical presence. The whole Worldline notion can easily be physically contained in a pill casing; for the rock pieces, a large dump truck might be necessary, as it was for Mayor Drapeau’s demolition of Vazan’s 1976 Corridart work.

Assembled in rows, Vazan’s rocks suggest lines and line theory, while they also refer even more strongly to massive fortifications, not only of the military sort but, above all, of a religious nature. Indeed, on at least one level, Vazan’s work is about religion, in the larger sense of sacred synchronicity with the highest cosmic forces. Perhaps it is in this celestial clock, both logical and mythical, that reason and eternity intersect.

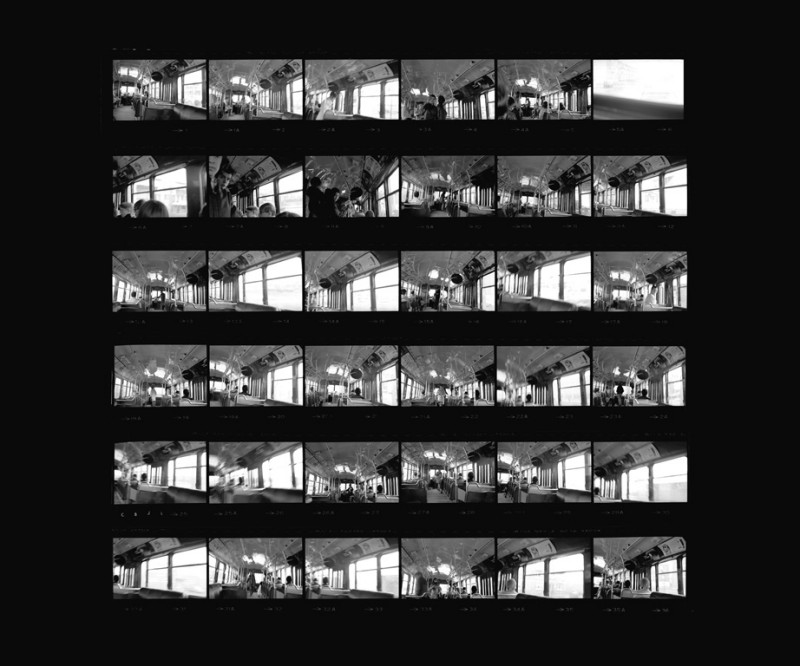

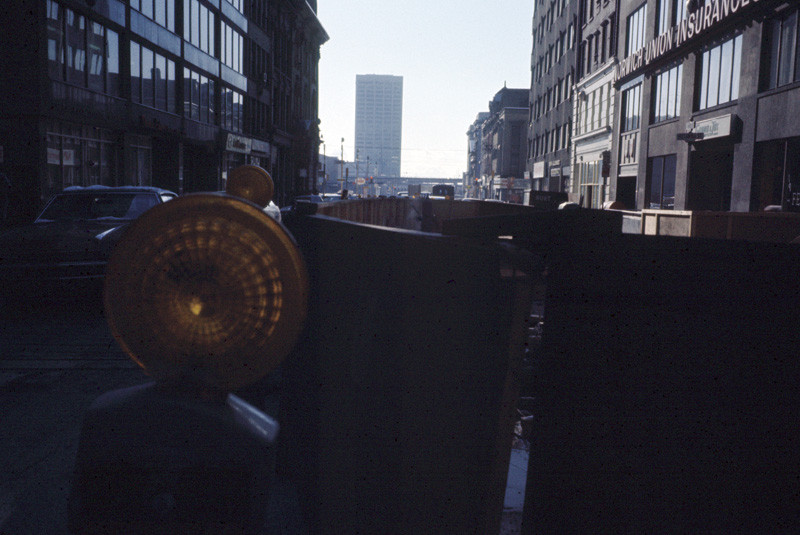

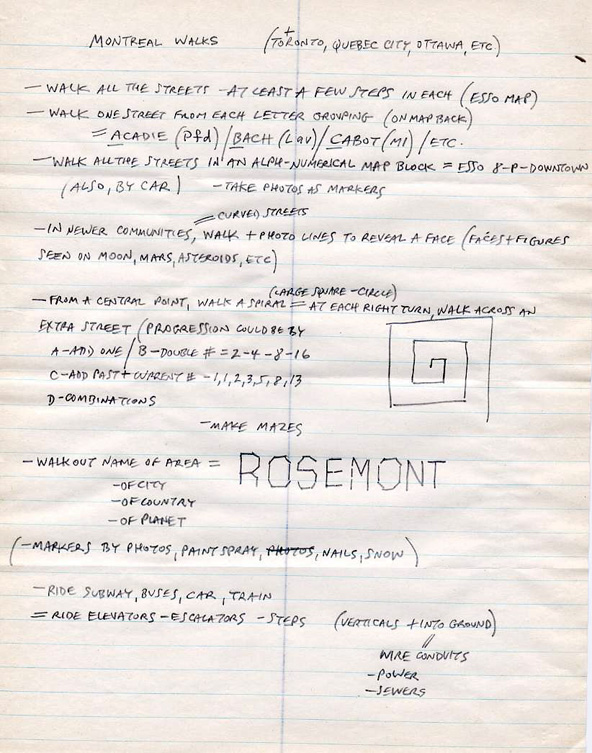

Indeed, Vazan came to know precisely how to situate imagined eternity – something by definition unknowable – in a contrasting three-part framework of a type of time that is conceivable – beginning, middle, and end, or prologue, action, and conclusion. Many of Vazan’s land-works physically include written records of their earlier planning stages, with build-ups of smudgy numbers, letters, and graph lines; the sketching out of concepts and the so-called finished art are intentionally spliced together. In conceptual art in general, all items somehow attached to the planning, making, dissemination, and, possibly, dismantling of a given work of art are theoretically encompassed within it. Ultimately, an art form becomes “everything” in a conceptualist worldview alert to all types of ecology and relatedness.

Like some other conceptual artists of his generation – Hans Haacke and Michael Heizer – Vazan dramatized the notion of inter-connectedness, and of open systems and open forms not delineated by a clear outer edge. Vazan’s art, however, is characterized by a sense of here-ness, as opposed to there-ness; Worldline is spellbinding even if we can’t imagine its extension around the globe. As well, Vazan gives us the sense that “invisible” elements, such as pure space, are in fact arranged according to a preordained order, a possibly secret language demanding to be cracked wide open.

Certainly, it is in the give-and-take between physical and conceptual notions that we arguably discern an individual style in work such as Vazan’s. On the other hand, the inferred – or perceived – presence of a higher order, logical or other, tends to de-individualize conceptual art, land art, and other forms of art. Ironically, that leaves us with the artist’s actual name, a last vestige of the “artist’s touch” and certificate that the work is, indeed, original, one of a kind.

Achieving perfect balance between idea and form – information to be read and mass to be felt, as in the inherently attractive, textured surfaces on the stone – is, of course, Vazan’s first aim. That this balancing act might lead through a time warp into a transcendent felt realm of immensity and sacredness is, no doubt, the next step. The third is, arguably, getting the viewer to “grab hold” of any number of usually available lines in a given Vazan piece and to metaphorically follow it into an imagined labyrinth of prehistory and an age blessed by strict faith in the “basics” such as time, interval, space, sun, stone, and fire. For example, where do the wriggly intaglio lines in some of the boulders lead? Back to human beginnings or forward toward a heightened sense of the artist’s personal, moment-to-moment involvement in his work?

In a way, the organic-looking, curved markings reiterate both the role of nature in Vazan’s work and the artist’s equally strong allegiance to culture – and the man-made. Furthermore, the drilled lines, cruelly “burned” into the stone, announce the very real role of time in the making of his work. Obviously etched with a power drill, the lines pit modern, fast-forward mechanical time with the seeming endless time that it took for the rock to be made. Such temporal contrasts and frictions abound in Vazan’s personal psychic “quarry.”

Certainly, for all the visual and conceptual economics of a typical Vazan piece, it becomes clear to anyone scanning the artist’s long career that lines have as many shades of meaning as the whole colour scale. Line functions as information, as guiding thread, as visual expressionist gesture, as time, as decoration, as scientific tool, as a link to craft traditions, and as Platonic symbol.

This magical mixture of themes and psychological sequencing does not deconstruct into its simple ingredients because the final resonance of any given Vazan piece includes a sense of the artist’s presence, if only as the shadow that we see in some of his photographs. He, too, is an object, just as the inert stones or shallow edges of sand are in his celebrated footprints in the beach. Of course, also separating Vazan out as original is his apparent need to cause things, people included, to materialize – to have a sense of identity, one that continues to grow. This is in contrast with the “dematerialization” obsession of many conceptual artists. As well, it is opposed to, and in conjunction with, that lowest common denominator of all forms, the single point, so utterly conceptual, yet so crucial to the whole psycho-conceptual act of seeing shape.

Known internationally for his Land Art works, Bill Vazan (Toronto, 1933) has played an important role in the Canadian art world. His works have been exhibited throughout North America and abroad. In 2001, the Musée national de beaux-arts du Québec mounted an important exhibition titled Bill Vazan. Ombres cosmologiques. This exhibition was also presented at the Kelowna Art Gallery in British Columbia (2002), the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography of Ottawa (2003), the Nickel Arts Museum of Calgary University in Alberta (2004), the Centre d’exposition de l’Université de Montréal (2004) and the Musée régional de la Côte-Nord (2005).

Henry Lehmann teaches art at Vanier College in Montreal and writes weekly art reviews for The Montreal Gazette.