[Fall 2007]

Kassel, Germany,

June 16 – September 23, 2007

“The big exhibition has no form.” This statement, the first sentence of a preface to the catalogue by curators Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack, set the tone for this year’s Documenta. This exhibition was indeed formless, sprawling from the heights of the Cascades at Park Wilhelmshöhe to an enormous, tent-like temporary building, the Aue Pavilion, that was erected on the vast lawn of the Orangerie. On its path it filled the Museum Fredericianum, the Documenta Halle, and the Neue Gallerie and permeated several other venues. It spread out in time as well; a large historical component to the exhibition reached back as far as the fifteenth century. A matching formlessness was found in the exhibition’s three leitmotifs, which were so broad as to become near meaningless: “Is modernity our antiquity?” “What is bare life?” and “Education: What is to be done?”

The curators’ insistence on “no form” could be read as an honourable attempt to avoid a partial, biased view, but what kind of exhibition does formlessness generate? An exhibition, if Documenta 12 was any indication, that in the absence of strong curatorial interpretations reflects the confusion and complicatedness of everyday life “as is.” Interventions in everyday life and in-situ installations, however, were noticeably few and far between. Life “as is” was not so much infiltrated as it was simulated. Documenta 12 presented a virtual world, like the World Wide Web (but without search engines). The formlessness of this year’s exhibition can be compared to the current eruption of vernacular photography and video that, absorbed by the computer, creates a vast and formless overlay of real life, millions of points of view that are accessible to all.

Suppressing the authorial view in a large exhibition presumably opens the field for the personal poetics of the viewers. As we do on the Web, we are free to draw our own connections, make our own discoveries in a sea of images. But it is easy to get lost in uncharted waters.

Canadian artist Luis Jacob’s installation Album III (2004) reflected the formlessness of the exhibition on a small scale. Hundreds of photographs from mass-media sources, many of them portraying works of art, were displayed around the walls of a large gallery space in the Fredericianum. They formed an open archive, without beginning end, making poetic associations that depended largely on what viewers could bring to it. Obviously, this anarchic structure works better on a small scale than in the exhibition at large, but even here, the effect of the barrage of images was one of bewilderment rather than of pleasure or insight.

Other photographers brought more structure to their collections. Zoé Leonard’s Analogue (1998–2007), with a focus on specific objects and thematic organization, showed more of an authorial input. Taking shop windows and streets in her native New York and other cities in the world as a starting point, she registered the transformation of urban landscapes in the face of globalization and followed trajectories of consumer goods, marked by brand logos, all over the world. Leonard’s rows of C-prints and gelatin-silver prints provided a nostalgic view not only of a threatened vernacular aesthetic of privately owned shops, but of analogue photography as well. The excessive number of photographs without captions or clear categorizations confused the narrative, however, leaving viewers to their own aesthetic musings and poetic correspondences, much like the exhibition at large.

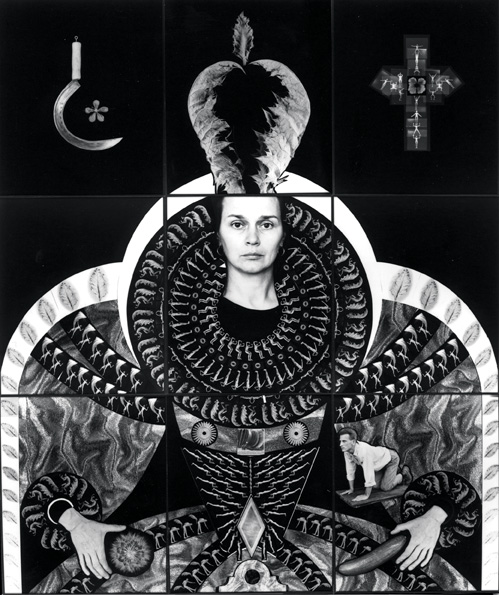

“What to do under the pressure of the constant flood of information?” is a question that Polish artist Zofia Kulik posed in the catalogue. Working with a huge collection of images in which her own work and personal mementos are mixed with socialist, post-socialist, and neo-capitalist imagery, she answered herself: “Subordinate it to a pre-existing pattern, for example that of a carpet.” Since 1987, Kulik has been transforming straight photographs into tableaux of ornamental motifs. An endless collection of real-life images are morphed into a work of art that scrambles their ideological messages. They are as intentionally unreadable as the untitled images (1992–96) of Indian artist CK Rajan. He responds to the overwhelming visual culture with collages that exaggerate the spectacle of mass-media photography through jarring or surreal juxtapositions.

Interpreting her collection of documentary photographs of political rallies, protests, and graffiti in several European and Middle Eastern cities, Dutch artist Lidwien van de Ven took a more narrative control, sorting and associating the diverse images, making connections between different geographies and events. In Document (2007), a photographic installation of photographs taken between 2000 and 2006, her mostly black-and-white photographs were interspersed with white posters, as if to remind us of the invisible parts of the stories.

The lack of a clear political message in all of these photographs made this work about the media rather than the message. This set it apart from more direct political work such as that of Mary Kelly and Jo Spence of the 1970s and 1980s, which was also shown. Kelly and Spence’s work focused on the lack of representation of woman’s experiences, but in this large, formless exhibition, the political power of these photographs seemed diminished.

Similarly, the urgent witnessing of social inequities by African photographers lost its potency in the unfocused exhibition. Nigerian George Osodi’s series of digital photographs Oil Rich Niger Delta (2006) showed how little of Nigeria’s oil wealth has trickled down to the local people. Osodi, who is from this region, considers himself equally a photographer, artist, and activist. Through his photographs, many of them distributed by Associated Press, he aims to expose the inequalities created by oil, as well as the resilience of the landscape and the culture of his people. Guy Tillim, an award-winning photojournalist from South Africa whose work increasingly appears in contemporary art settings, contributed a fascinating series of photographs of the 2006 elections in the Congo, Congo Democratic (2006), as rich in symbolism and aesthetic enhancement as it is in conveying a reality away from the focus of the main news.

Disciplinary boundaries between photojournalism and art photography have long become obscured, and they are even more difficult to maintain as the complexity and range of contemporary photojournalism increases. But what exactly turns a newspaper photograph into a work of art is not as pertinent a question as whether a photograph retains political potency when recontextualized in the contemporary art setting. Whereas in Documenta 11 the inclusion of artists of the Southern hemisphere may have been too overly insistent, in Documenta 12 their voices were unobtrusively integrated. As a result, they were as lost in the cacophony of the exhibition as everyone else was.

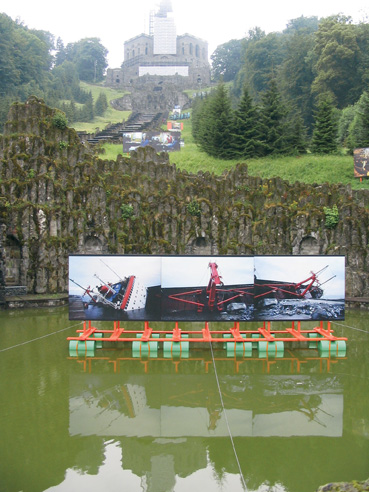

The context of politically charged photography has been an ongoing concern for Allen Sekula. At this Documenta, he showed billboards on sites away from the main venues. Shipwreck and Workers Version 3 for Kassel (2007) were placed around the centuries-old artificial cascades in Bergpark Williamshöhe, a popular tourist attraction. The site looked in disarray this year because of the ongoing restoration of the Hercules monument that towers over this largest hillside park in Europe; the water was turned off and the tower wrapped in scaffolding. In the bottom pool that still contained water, Sekula placed his Shipwreck. Ostensibly it is an ironic comment on the megalomaniac dreams of an eighteenth-century German landgrave, but one wondered if the irony was meant to be extended to the grounded aspirations of the mega-exhibition in the city below. The shipwreck’s statement felt complete in its deadpan humour. The series of billboards Workers, placed on the steep slope beside the cascades, was described by Sekula as “a Portable and Temporary Monument for Labour.” The series seemed pat in the obvious contradiction of everyday working lives and the monumentality of the setting. Too much labour was spent and too many resources were exploited for Sekula’s monument to the everyday. In this excess, it reflected the exhibition as a whole.

The formless exhibition turned the everyday into a monumental spectacle. Was the Aue Pavilion, nicknamed the “Crystal Palace,” really necessary? If formlessness is inherent to a big exhibition, as the curators claimed, couldn’t the bigness of Documenta 12 have been curbed to retain a form? It is true that the more the world opens up, the more difficult it becomes to document it. In Documenta 11, Okwui Enwezor dealt a final blow to Western isolationism with the inclusion of many artists of the Southern hemisphere. And Catherine David’s Documenta 10 included myriad works from the 1960s and 1970s to provide a historical context for contemporary art. Documenta 12 did all that and more. A paragon of inclusiveness, the exhibition reached a point at which its erasure of borders began to erase its own raison d’être, which is to document and crystallize a moment in the state of the world’s art. It goes without saying that this can never be done in an accurate, objective way by any curator, but much of Documenta’s fifty-five-year attraction comes from the variety of curatorial viewpoints that it has shown over the years. Of course, Buergel and Noack’s lack of focus provided a viewpoint nonetheless, even if it was a bewildering one.

Petra Halkes is an artist and writer. Her book Aspiring to the Landscape was published by the University of Toronto Press in 2006.