[Fall 2007]

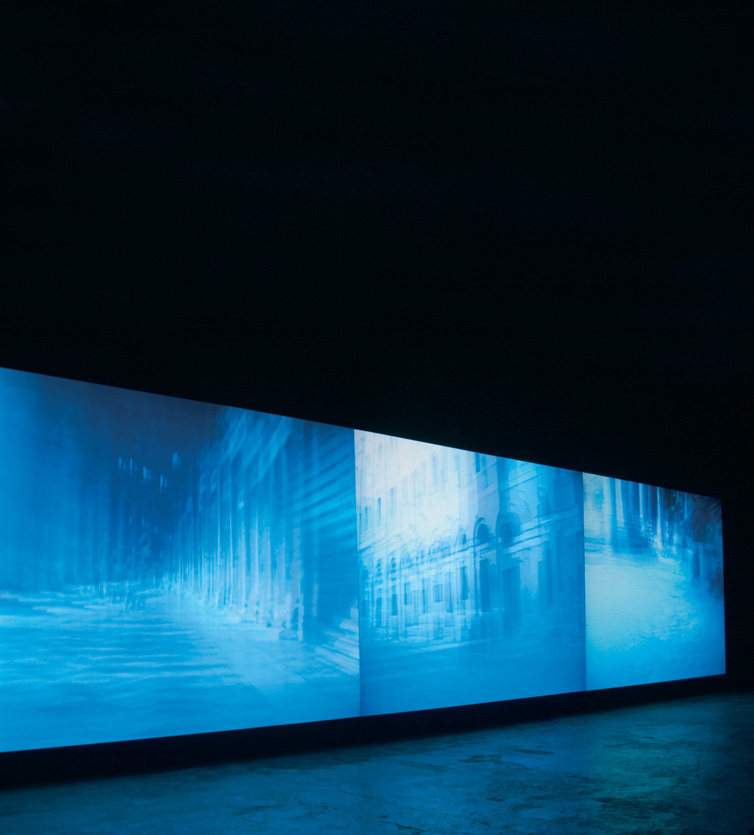

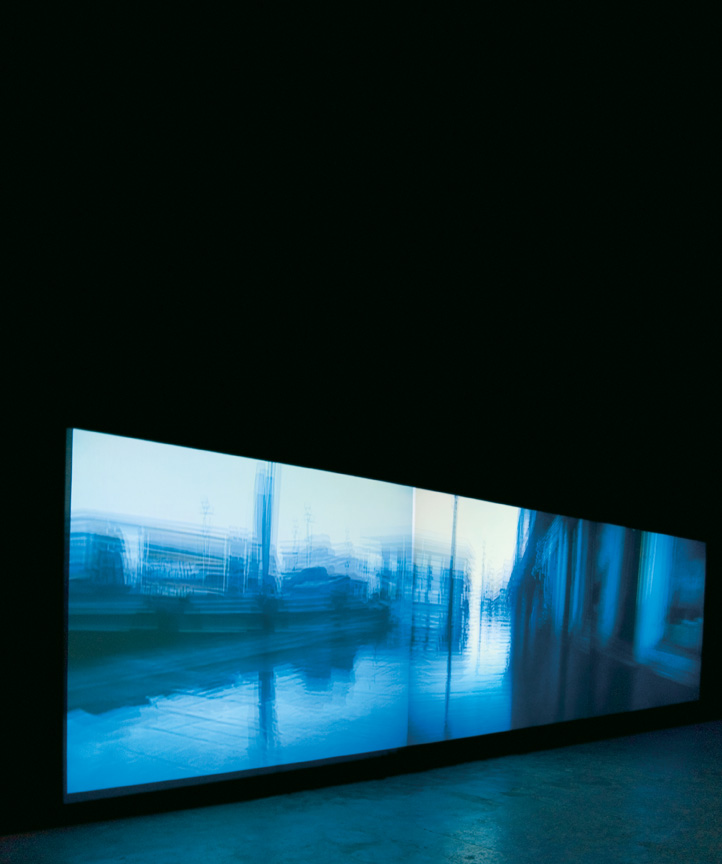

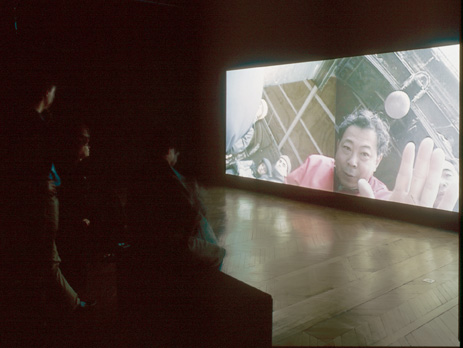

Exhibited as a triptych video projection, the edited video that resulted from the dog’s view of the Italian city offers awkward and destabilizing views of the urban built environment, the city’s inhabitants, and the hordes of tourists populating the walkways and canals. Through this artwork, Sterbak questions the subjective act of viewing within the known context of tourist sites.

by Alain Laframboise

The videograms reproduced here are excerpted from Waiting for High Water. Let’s start with a clear, succinct description of the piece by Catherine Bédard, curator of the exhibition:Waiting for High Water is the second part of a multiple-projection installation presenting a videographic “composition” produced with the assistance of a dog named Stanley, who was used as the camera operator. The first part of this project, titled From Here to There and filmed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the winter of 2002–03, was produced for the Canada pavilion at the fiftieth edition of the Venice Biennale. …Waiting for High Water was seen for the first time in 2005 during the first Prague International Biennale of Contemporary Art. …Waiting for High Water is a triple projection on a single plane. A single miniature camera was attached to the top of Stanley’s head to shoot the first part of the project, while a three-camera device was used to shoot Waiting for High Water.1

Knowing this gives viewers a better understanding of the particular nature of the videograms in Waiting for High Water, which results from the camera angles and specific framings obtained by Stanley, the “camera-dog,” the unsuspecting capturer of visual sequences subsequently sorted through by the artist. Thus, the camera operator has a name, a piece of high-tech equipment, a set through which to move, and whatever he does is performed as part of the script (project) of his director. He travels around one of the premium sites of cultural tourism, one of the most saturated with art and literature: Petrarch, Montaigne, Byron, Chateaubriand, Goethe, Proust, Rilke, Mann, and Brodsky 2 are among the bards who have celebrated the Serene City, its inhabitants, and the architects and artists who have worked there over the centuries. Stanley, however, does not see Venice as the site of a myriad of cultural condensations. In this sense, the dog’s-eye view deprives us of Venice; but do we really need to see it yet again through human point of view, or from a balloon, as in the eighteenth century, or from a helicopter?

Hubert Damisch has discussed Sterbak’s project with regard to the height of the gaze: the viewfinder – the three cameras harnessed to the dog’s head – entails a view of the world that is close to the ground, animalized.

Before talking about the videograms, let’s talk a bit about the video. Damisch cannot help but make a comparison with The Man with a Movie Camera, a film by the Soviet director Dziga Vertov (1896–1954). Vertov was one of the founders of the Kinoks, a group that wanted to capture life as it happened through the impartial eye of the camera. Jean Mitry commented on their technique: “The director, obscuring himself behind the absolute objectivity – or what passes for it – of the camera, recorded a quantity of documents based on a fairly vague theme that served as a guideline. The art consisted simply of ‘framing’ shots, putting them in order, and editing them together.”3

Vertov’s experiments were instrumental in emphasizing the importance of editing – understood as the “organization of chance” – which made it possible to convey or give meaning to recorded images. Later, Lev Kuleshov, at the Moscow Technikum, showed his students that “a film – at least its emotional or dialectical development – is constructed in the viewer’s mind starting from the formal organization of images.” Kuleshov had his students measure the impact of the “psychological capacity” of these relationships among images on the viewer’s mind. He taught them that the “editing procedure appears . . . as the tracing of workings of the conscience – that is, of the judgment that one constantly makes about the world and about things.”4

…the dog’s-eye view deprives us of Venice; but do we really need to see it yet again through human point of view…

Thanks to contemporary technology, Sterbak has found, one might say, a more objective operator than Vertov’s and has allowed herself to take liberties with editing that Kuleshov might have envied. The videograms, made from the same triple-camera device as the installation, have a similarly significant visual impact. Withtheir unusual points of view and framings and their uncommon horizontality, the photographs retain much of the suggestive power and destabilizing character of the three-channel videographic montage in the installation, but they blur — without concealing completely — the sutures between the three shots that create a panoramic view.

Tourism may lead to the production of cultural reportage, documentary, and what is called art films. All of these forms belong to agreed-upon languages. This is how things gain consistency, “reality.” It is also how they are defined and shared. And it is in this context that we define what an art practice is and, as a consequence, what an artist is. Belief, after all, demands very clear definitions and territories.

But there is room to speak of other things, to create differently what could be called “one’s own reality.” For Sterbak, creating does necessarily not mean working with lines, colours, volumes, spaces. In her body of work, arrangements, associations/dissociations, and methods are more important than order of representation. Form is always subordinate to the perceptions, effects, and emotions that she induces. There is no representation (imitation) of or identification with the animal in Waiting for High Water. What the artist is attempting is a rapprochement with the movements, the stops and starts, of the animal’s body as it gathers “ocular” information of its position on an environment that it is exploring. The rapprochement does take place, even though it is through a device that, due to its prosthetic nature, is part of neither the human nor the animal. Waiting for High Water might thus be an attempt at establishing an “in-between.” Human technology combined with animal behaviour may be capable of simulating, but it is incapable of reproducing. This early attempt at communication between two species is shared with the viewer.

Sterbak’s practice does not consist of imitating or identifying with the animal, or of establishing correspondences between it and a walking human. Rather, a bridge is built between two forms – two heterogeneous relationships – through connection with a specific urban environment. The dog’s “gaze,” as we imagine it, is as much the result of scientific observations as of our fabrications, but the experiment that is Waiting for High Water implies a change in how we look at the world – an intuition of, if not participation in, a “nature” that is foreign to us. The familiar animal that is Stanley leads his mistress toward an experience of something that is unknown to him. But the artist’s dog, for her as for us, belongs mainly to the animal species and to animal reality.

This work is about overriding symbolic human–animal relationships as we know (or imagine) them in society and glimpsing, beyond our human emotions and subjectivities, at a facet of a reality that escapes us. Let’s call it tourism, if we wish – or, better, a hint of an incursion into the world, if not forbidden, at least almost inaccessible, of animal-ness – through the inevitable distortions of the human eye.

What if, as Deleuze might say, tourism were to become an affair of intensities? What if, to do this, it operated outside the fabricated field of the organic body, as we conceive it? What if desire were conveyed through a different arrangement of the body? What if experimentation led to or created other circuits? What if opening oneself, as Sterbak does, to the multiplicities and intensities that pass through the body meant that it needed to invent other situations for itself – oblique approaches to discovering what it is and what it might be or become? Who could then deny that there may be thought outside of philosophy?

The problem is not that of a human being this or that, but rather of an unhuman future, a universally animal future: not thinking of ourselves as beasts, but undoing the human organization of the body, each discovering his own zone and the groups, populations, and species that inhabit it. By what right will I talk not of medicine without being a physician, if I talk about it like a dog?5

1 Catherine Bédard, essay in the Waiting for High Waters catalogue, which also has an essay by Hubert Damisch titled “L’Animal à la caméra – Stanley’s video” (Paris : Canadian Cultural Centre, collection Esplanade, 2006), p. 31 (our translation).

2 Joseph Brodsky (1940–96), a poet born in Russia who became a U.S. citizen in 1977. Winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1987. In 1992, he published Aqua Alta, to which Jana Sterbak alludes in the title of her installation.

3 Jean Mitry, Histoire du cinéma 2 (1915-1925) (Paris : Éditions universitaires, 1969), p. 504 (our translation).

4 Ibid., p. 505.

5 Gilles Deleuze, “Lettre à Michel Cressole,” in Michel Cressole, Deleuze (Paris : Éditions universitaires, “Psychotèque,” 1973), p. 117 (our translation).

Alain Laframboise carries out an artistic investigation of three-dimensional structures (his boxes) and photographs that explore the mechanisms of representation. He teaches art history and theory at the Université de Montréal. His works are included in numerous private and public collections. In Montreal, he is represented by Galerie Graff.

Jana Sterbak is a Czech-born Canadian artist who lives and works in Montreal and Barcelona. Since 1978, her works have been regularly exhibited in Canada and abroad. She has employed a wide range of media to build a corpus focused on the human body. She has had numerous solo exhibitions around the world, including at the Museum of Modern Art of New York, the Musée d’art moderne in Saint-Étienne, France, the Galeria Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and the MOLMA Kunsthall in Sweden.