[Fall 2007]

Toronto,

May 1 – 31, 2007

Every May, Toronto is almost entirely given over to photography, in the guise of the CONTACT Toronto Photography Festival. This past May was the festival’s eleventh annual incarnation. The theme this year was “The Constructed Image” – which, in my estimation, is more or less code for “The Digitalized Image.”

CONTACT is a gigantic festival, and it is growing steadily more gigantic all the time. This year, it offered so many exhibitions, public installations (in the subway, etc.), lectures, workshops, critiques, panel discussions, and screenings that it was just about as exhausting as the Toronto International Film Festival, which takes over the city the four months later.

You cannot see everything, and I didn’t try. What I did see were a handful of exhibitions – all of them digital-free – that might be described as CONTACT-adjacent.

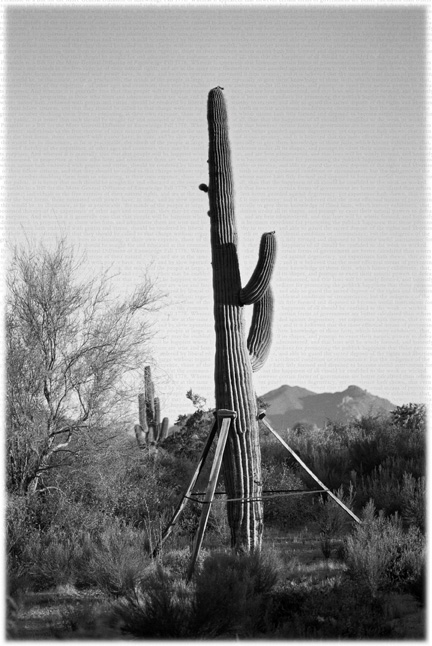

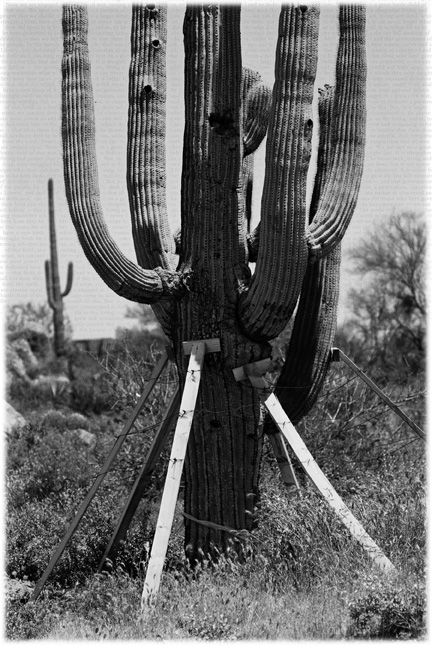

The first of these was an exhibition by Toronto artist Stan Denniston called Just Until at the Olga Korper Gallery. The exhibition consisted of large-scale photographs of saguaro cacti, and Denniston’s title betrayed something of the tensions inherent in the lives of these venerable plants – one almost wanted to call them creatures – which the artist had photographed near Scottsdale, Arizona.

The saguaro is a pretty majestic cactus. One Google search will tell you that a saguaro can grow to a height of seventy-five feet and live to be two hundred years old. A mature saguaro weighs over five tons. It is also an endangered species – though not in the usual way. The root system of the saguaro, although it spreads far and wide, is apparently quite shallow. It seems that the thing is very easy to tip over, all five tons of it, and the presence near to it of, say, a rumbling, vibrating, earth-shaking construction site is enough to cause it to keel over. Not a happy fate for a national treasure (the flower of the saguaro is Arizona’s state flower). As a consequence, it is now required by law that each vulnerable saguaro be propped up.

Denniston has always had a quick and felicitous eye for metaphor. So for him, this rather poignant propping up of the saguaro quickly took on symbolic meaning: the cacti became fragile, faltering icons – emblems of rugged American individualism that now, in an anxious and morally murky America, have been repositioned as emblems of uncertainty. Once proud and unassailable, the saguaro is now an image not only of “environmental degradation,” as the artist’s statement suggests, but also of American infirmness: the propped-up saguaro as Uncle Sam – on crutches.

This sense of the fragility of the giant cacti was made to seem even more telling by the fact that Denniston documented them in what the gallery referred to as “barely coloured photographs” – by which was meant colour that was about 10 per cent of normal. The photographs looked black and white at first, and then, when you looked more closely, you could see that each of them glowed faintly with a gently phosphorescent green – a sort of failing memory of colour.

If you looked even more closely still, you noticed that the background of each photograph – what looks at first like bleached, white-hot Arizona sky – was, in fact, a field of very lightly printed text: American-sensitive documents such as the Bill of Rights (1789) and the Gettysburg Address (1863). I was not entirely sure, however, what these stirring and almost subliminally present documents really added. For me, the work was plenty strong enough – without its being propped up, like the cacti, with these exemplary texts of American idealism.

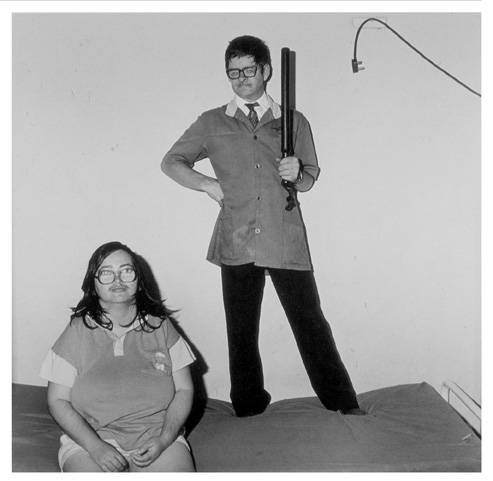

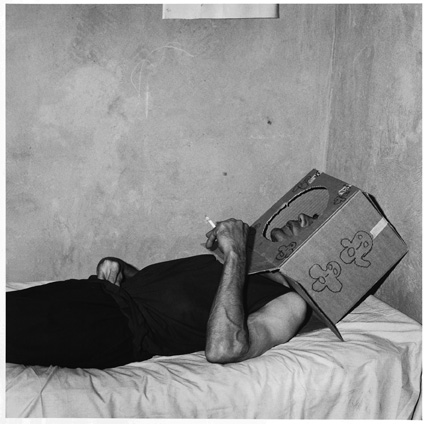

One of the most enjoyable and demanding of the CONTACT exhibitions was a selection of works by New York–born South African geologist and photographer Roger Ballen at the Clint Roenisch Gallery. Ballen’s work, though it is now widely and even ecstatically celebrated, eagerly sought by museums, snapped up by collectors, and enshrined within the covers of five lavish books – the most recent being Shadow Chamber (Phaidon, 2005) – is often difficult.

What seems to make Ballen’s photographs shocking and disturbing, for many people, is the queasy-making way he has of using a flat, impassive, apparently documentary technique in his pursuit of the outlandish. He works with an almost appalling kind of directness, which often seems guileless and almost amateurish (his use of flash, for example, is something less than subtle and sophisticated). He uses this deadpan directness to construct suites of often-unappetizing vignettes and tableaux featuring South Africa’s marginalized poor, shaping and wielding the very textures of their economic deprivation and concomitant problems with health and emotional adjustment into hair-raising moments of social surrealism.

It is clear that Ballen works closely and collaboratively with his subjects. They all seem to be in this thing together. And yet his work is haunted by the spectral possibility that he has somehow “exploited” his subjects. Does the man seated at the table (with one small, pathetic, silly fish on his plate) in Lunchtime (2001), for example, really want to be immortalized adjusting his upper plate? Or did Ballen simply think that he would make an arresting photograph?

Critics have tried to soften the blow of Ballen’s incorrigible, unapologetic photographs by linking them to sturdy names such as the playwright Samuel Beckett (the odd, theatrical settings that Ballen contrives) or the painter Francis Bacon (the apparent sublimity of mess and rot and anguish). But in the end, what it comes to is just Ballen and the viewer in uncomfortable confrontation.

It’s a question, I suppose, of what we’d like to forget (or never know) and what we can bear to be reminded of. I found myself taking the easy way out with Ballen, constantly gravitating to his more formally composed, more ingeniously constructed, less grotesque photographs, such as his Boxed Rabbit (2002), or his Hanging Pig (2001), with its little pig being hoisted off the ground by a rope dangling from two dirty, disembodied feet at the top of the frame. But I know what I’m doing here: I’m taking refuge in the familiar, art-historical pleasure of collage and the deftness of the picture’s design. Which is mostly to have avoided the issue. The surrealism here, the formal design of the work, is really just a perk. The real stuff of a Ballen photograph lies in his people in their environments, and the abyss that opens between them and us – and how to get over it.

One of the finest of the CONTACT exhibitions was never planned as a festival exhibition at all: Edward Epstein’s mounting of photographs by the remarkable Gyorgy Kepes at his Gallery 345 came about simply because Epstein suddenly had the opportunity to show a selection of photographs from the Kepes estate, and he wisely jumped at the chance. It is more or less a coincidence that the exhibition took place at the same time as CONTACT.

Gyorgy Kepes (1906–2001) is perhaps best remembered today as the founder, in 1967, of the Centre for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT. But his life as an artist, designer, photographer, writer, and teacher goes back to 1930 when, at the age of twenty-four, he left his native Hungary to join his friend and collaborator, the great Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany. Both Kepes and Moholy-Nagy fled Germany during the rise of the Nazi party, and in 1937, both fetched up in Chicago at the so-called New Bauhaus (soon to become the Chicago Institute of Design). Kepes was made head of the Light and Color Department. He joined the faculty of MIT in 1946, teaching visual design. His books – especially his Language of Vision (1944), The New Landscape in Art and Science (1956), and the seven-volume Vision and Value series (1965-66), for which he was editor as well as contributor – were enormously influential at the time, and are remembered fondly still (and treasured as collectibles) by artists and designers for whom his spirited erasing of the lines between fine art and science spelled creative liberation.

Kepes was a superb photographer. Like Moholy-Nagy, he was a restless and relentless experimenter with the camera, pushing its limits by shooting through screens and distorting glass, choosing odd and often dizzyingly elevated angles from which to make images, capturing unlikely shadows and unusual textures, creating inventive lighting effects, and generally attempting to extend the boundaries of the photographic act. And like Moholy-Nagy (as well as Man Ray), Kepes also made photograms (of which there are several in the Epstein show): cameraless photos produced by placing objects on photo-sensitive paper and then briefly exposing the paper to the light.

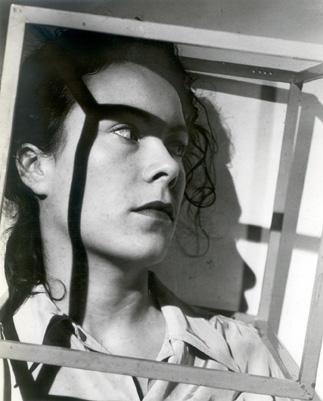

Kepes’s beautiful Juliet’s Shadow Caged (1939) is typical of his work: here, his wife, Juliet Appleby Kepes, is recontextualized by a structure – part solid and part shadow – that confines her even as it tenderly redefines her. There were twenty-five works in the Epstein exhibition. Some of them were vintage prints. Most were gelatine-silver prints dating from 1930 to 1973, printed by Kepes himself and gathered into a few exquisitely produced portfolios. All of them were the product of Kepes’s invigorating quest for pictorial invention and new imagistic meaning.

Toronto writer, critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author, or co-curator, of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe and Mail.