[Summer 2008]

Galerie Roger Bellemare, Montreal

October 6 – October 27, 2007

The stark elegance of Charles Gagnon’s photographic oeuvre is one of its defining characteristics. It is always, however, underscored by powerfully enigmatic markers. Those indexical markers are like fingers pointing to unseen presences – or a transcendent reality. Gagnon was always a champion of graphic ambiguity. While many pigeonholed his photography, claiming that it had much in common with the post-war American school of street photography as practised by his friends Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, among others, he was always more subversive and provocative. He was a searcher in the best sense of the word. He wanted to capture – or at least suggest – a truth that, for him, moved furtively just behind the lens, under the surface of the retina, just below the threshold of representation.

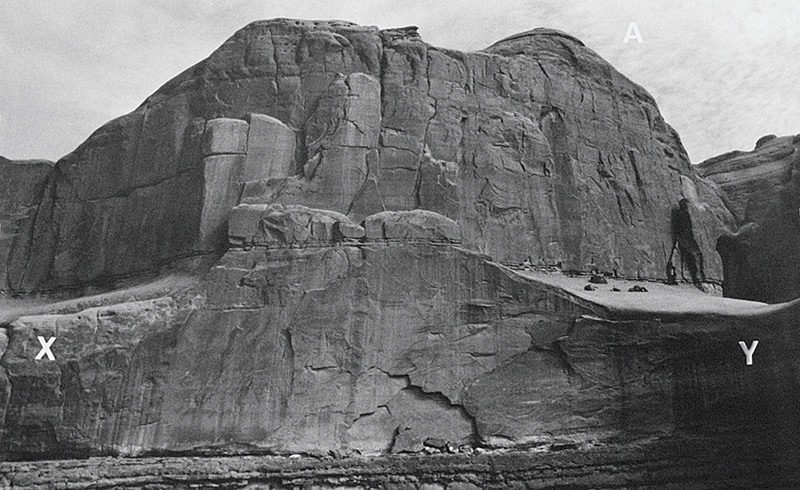

Given his penchant for compositionally eloquent, if austere, urban spaces, it was a surprise to some when Gagnon turned to the natural landscape in his work of the 1990s. The truth is, this transition was less one of rupture than phenomenal continuity. He was as able and experimental in his photographic work as he was in his painting, and his powerful union of the two late in life was a genuine epiphany for old fans and newcomers to his work alike. His thorough mastery of the photographic medium allowed him to revisit and reinvent the lexicon of survey photographers of the American West such as Watkins, O’ Sullivan, Haynes, and Jackson, but with his own cool, cerebral, irreverent, and very-late-modernist set of concerns.

In fact, I often conversed with him in the early 1990s about the work of the post-Civil War government survey photography of the American West. We often spoke of our mutual admiration for the work of Timothy O’Sullivan’s remarkable photographic artefacts from the Wheeler and King surveys. He was starting to use those artefacts as a fulcrum point for his own photographic work, bringing his own quintessentially cerebral optic to bear. He spent time in that landscape, used that earlier work as anamorphic prism, and then underscored it all with a singularly fresh and seductive conceptual grid all his own.

Gagnon was unusual in that he had two parallel and equally illustrious careers: he was at once one of the finest painters whom this country has produced and one of its finest photographers. The cross-pollination and tension between these parallel approaches was continual and dynamic throughout his lifetime. He once famously stated, “Art is not a means of communication. Rather, it is a form of communion.” And he meant that equally, of course, for both his endeavours – and for all art.

In the later photographic work, Gagnon flirts with creative taxonomy (the insertion of letters and numbers into the landscape) even as he reaches for a truth far beyond its ken. And this was nothing new, really, if one thinks of his integration of linguistic fragments into all periods of his abstract painting and earlier black-and-white photographs (such as the famous boarded-up and palpably enigmatic “blue room” window).

Gagnon always radically over-determined content – using an extensive inventory of means that he had built up over the years – in an effort to achieve the radically indeterminate. This is true of all of his work: photography, painting, prints, film, sculpture (his glorious box constructions). His playful markers and integration of tools of measurement (rulers and so forth) ironically point to the absurdity of fixing, tier-like, artificial hierarchical categories onto canons of acquired perceptual truth.

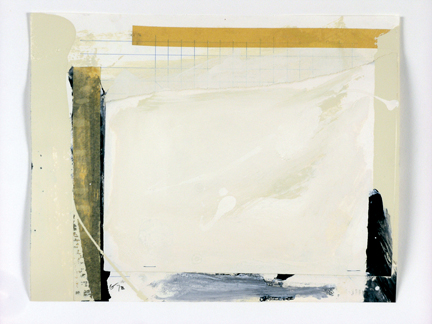

In his Histoire naturelle series (1991), Gagnon achieved a rare watershed in the formal invention of his work, pairing wonderfully reduced chromatic panels (still showing the exalting and seductive brushstroking that was his hallmark from the early years on) with lustrous black-and-white-and-grey photographs taken in the wilderness of the southwest United States. These works were like epistemological switch-boxes between real and invented iconographies and thoughtscapes, and they finally resulted in a stereoscopic merger of photograph and painting in one image. The epistemological and ocular-centric issues engendered by these works make them no less radical today than when they were executed those many years ago.

Works in the Mythe III series (1998–99) shown at Roger Bellemare (beautifully installed by gallery owner and curator Bellemare in a way that would, I think, have greatly pleased the photographer if he were still with us) lay bare his vibrant and still topical epistemological concerns and his lifelong search for beauty and mystery. Between seer and seen, knower and known, Gagnon interposed an otherworldly, haunting, liminal, and, finally, unavoidable truth. He always moved onto the threshold of the world, like Cézanne confronting his beloved Mont Sainte Victoire, and that threshold becomes ours, in turn, as we stare into and are seduced by his eloquent spaces of thought and vision. Yet he never supplied pat or easy answers to the Parmenidean puzzles that he posed there. Always, and in all ways, he left the issue of resolution, if not resolve, with the viewer as fully complicit co-author of meaning and interpretive mediator. I think that he had more in keeping with a photographer such as Ralph Eugene Meatyard, that Kentucky optician and savant, than with any other. Gagnon was an admirer of that work – Meatyard was one of his avatars. I remember many conversations with him in that regard.

The seemingly simple clarity of his photographs was always deceptive – reductively “simple” compositions that hid a wealth of meaning in plain sight – and this wilful duplicity was shared with his paintings. In the latter, the laying on of paint was such an epiphany of making that it often disguised, like perceptual camouflage, his darker content. His work is really all about immanence. Hidden presence. Being and mind. Human finitude. The works exhibited at Bellemare constitute a fitting coda to Gagnon’s lifelong project: to elicit the noumenal from the fabric of our lived experience and make it somehow palpable, nourishing, and enlivening to the thinking eye.

James D. Campbell is a writer on art and an independent curator based in Montreal. He is the author of over a hundred books and catalogues on art and artists.