[Summer 2008]

For thirty years, Chantal Pontbriand has been the guiding light of the magazine Parachute. From the beginning, she positioned it among the internationally significant magazines. In parallel with its publishing activities, the magazine organized a series of events and conferences that were just as notable. In April 2007, Parachute announced a suspension of its publication; in May 2008, it is hosting the international congress of IKT (International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art), held for the first time outside of Europe. We asked Chantal Pontbriand about the situation of contemporary-art magazines and the future of Parachute.

by Jacques Doyon

Jacques Doyon : I would like to know how you see the current situation of contemporary-art magazines, following your participation in the Magazines Project at Documenta 12 and the decision to suspend publication of Parachute after a repositioning that actually seemed to be a success.

Chantal Ponbriand : I’m very enthusiastic about the current situation of art magazines in the world; I’ll come back to this. This view might be surprising given the disenchantment that surrounded the announcement of the suspension of Parachute a year ago. This was a very difficult experience for me on a number of levels.

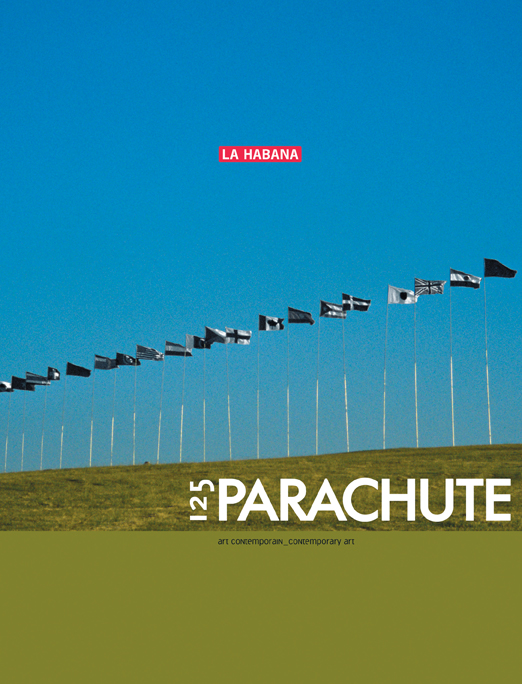

It was hard for me to accept the decision, but I recognize that the situation around the production and the very existence of the magazine forced us into it. I remain convinced that it was the best decision to stop before things collapsed. Since 2000, the new version had been a great success and I was very stimulated on the editorial level. On the administrative level, however, the shrinking of some grants and the stagnation of others made things impossible, despite a phenomenal increase in our independent revenues for this type of magazine. Parachute is an international magazine that requires resources and assets that cannot be found right now in the Canadian context. We announced a suspension rather than a definitive ending because I remain propelled by the anima that has carried Parachute since the beginning, an impetus revived with the new series. Each issue of this series launched us into an adventure; each one was completely different and extremely rich. This new way of working, emanating from a transversal axis based on a specific concept, enabled us to broaden our network of writers and artists around the world considerably; we were all challenged greatly by the issues. The fundamental subjects of human existence in the contemporary world were addressed: community, economics, work, resistance, democracy, violence, globalization; issues around the individual, solitude, anonymity, self-fiction, and psychic violence; and issues around the cognitive sciences and artificial intelligence, which are profoundly troubling. There were also the “city” issues, with each of those cities at a new geopolitical juncture for humanity: Mexico City, Beirut, Shanghai, Havana, and so on.

JD : How would you characterize Parachute among all of the very many contemporary-art magazines currently available? Following your experience at Documenta, would you say that there’s a form of community, or a network of affinities, among the different magazines at the international level?

CP : I see Parachute as a magazine of analysis, which acts as a groundswell for currents and trends, in harmony with them, yet with a “salutary” distance. It is a type of critical view that identifies connections – hyperlinks – among contemporary artistic practices, and thus creates meaning, a flow, an increase in meaning (in the sense of Bataille’s dépense). This is the only attitude that can produce joy, as Toni Negri speaks of it: a joy that allows us to advance, to go further in our lives. Joy allows us to go beyond comfort and conformism; it’s a risky activity. In a world that is losing its reference points, this is essential. It asks that we open ourselves and always venture into the unknown and into the floating worlds that are situated at the interstices between daily life and academic thinking. This is why Parachute is not perceived as a university journal, even though it includes quite a lot of theory. Art leads the way; theory is an indispensable tool today, but art allows us to deterritorialize theory and open other, less common paths to knowledge. Many people think that Parachute occupies a unique niche in this sense.

The experience of the Documenta 12 Magazine Project (http://magazines.documenta.de/) was wonderful for me, even though the opportunity to participate coincided with the difficult time when we suspended publication of the magazine. The large meetings organized in Johannesburg and New York were like a think tank for me, enabling me to reflect on the magazine and its role. I listened to my colleagues passionately recount their commitment to promoting ideas and transform contexts. The ninety invited magazines were chosen because they had an “agenda,” ambitious magazines with regard to content and ideas, magazines that want to change the world! These meetings continued in Kassel in the summer, and others were inspired by them. I also took part in a meeting in Istanbul in September during the biennial. A number of editors of new magazines shared their enthusiasm about Parachute with me, and I learned how some of them had modelled their magazines after it. All of this encouraged me to think that it will be possible to relaunch the magazine under new conditions that are more propitious to its development; it is, in any case, greatly desired. The experience of Documenta 12 enabled me to realize that a new phenomenon is blossoming in the world of magazines.

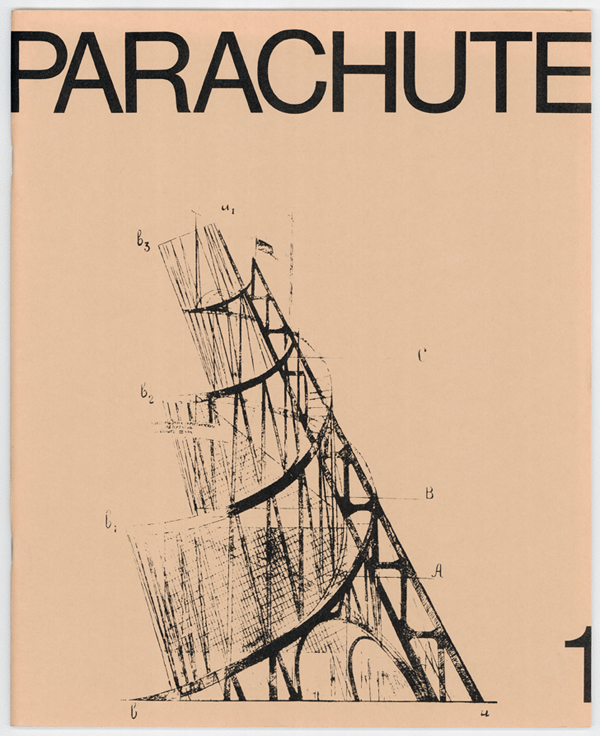

We saw a similar thing happen in the 1970s. Parachute was born in 1975, as were October and Macula; Artpress, Flash Art, Parkett, and others, soon before or after. These dynamic jousts took place in North America and Europe. The art world has broadened since then, and amazing magazines are springing up in Singapore, Bangkok, Seoul, South Africa, India, Cyprus, and the former East Europe. I attribute this evolution to these regions’ desire to broaden their vision of the world, to mark their territory, to participate in a process of contamination and dissemination of ideas on the international scale. These objectives have a kinship with Parachute’s goals when it started up. It’s a fascinating phenomenon, especially because it is based on publication projects that have a profile of high standards and of intellectual and editorial risk. The quality of the discourse and the wide spectrum of knowledge with regard to the artistic and intellectual scenes on a worldwide level are impressive. It is reassuring to observe that such forces are being deployed all over the planet, in reaction to the general lobotomization linked to the homogenization of cultures and to expanding capitalism, often without regard to the value of thought. Although the dynamic of contemporary art itself is now increasingly linked to capital and the market, one cannot help but observe that interstitial dynamics manage to insert themselves and that they are productive. There is a certain notion of resistance in this phenomenon that I think is very important.

JD : How do you manage to reconcile these contradictory pressures and keep a magazine independent while finding ways to increase its influence and have a significant impact on the international scale, particularly from the Quebec and Canadian context?

CP : Unfortunately, in Quebec right now we are going through a period of complacency and withdrawal linked to a sense of general self-satisfaction. We are revelling in our formidable culture on the official levels, but the lack of exigency is pathetic. There is lots of “culture” here: there are numerous artists, in all disciplines, and there is a plethora of structures to host them, but all this activity is like treading water. We suffer from a lack of means to develop, to outdo ourselves; the daily struggle for survival (due, among other things, to a galloping bureaucracy that pollutes our own work environments), to simply keep up with where we already are, impedes great debates and important advances. But these are indispensable if we want to stay in contact with, and be part of, the international scene. This is why, in the visual-arts field, in any case, it is difficult for us to become known and to work elsewhere. Today, we are in competition like never before with artists, curators, galleries, collectors, and even business people, who are very, very ambitious and want to be part of the international dynamic, who are hungry for opening, especially when they come from the countries of the former East Europe, India, China, or South America. We have to stop wallowing in a complacency that isolates us. We have to create the means to push ahead, demand this from our governments, and encourage market dynamics that can shake us out of our inertia and sense of being closed in on ourselves. I say this even more because I like, and am very stimulated by, the creative dynamics that are emerging here, but they could be stronger: they have the potential for it. What seems to be lacking in us as a community at the moment is only a sense of urgency.

This climate of self-satisfaction also explains why publication of Parachute was suspended, even though the magazine was in full flight. There was nowhere for us to go in this toxic context; the only thing that could have happened, without the “halt,” would have been to let ourselves fall and disappear completely due to the lack of support from the surrounding environment. It was better to announce a pause and try other ways of doing things than those predominating in the Quebec and Canadian context. One day – soon, I hope – it will be imperative to review programs and structures and to ask fundamental questions keeping in mind the objectives of quality rather than those of political correctness that prevail today, which tend to dilute everything into an average-tasting soup.

JD : In this context, what are the possible avenues for relaunching the magazine, and in what form?

CP : In general, state-supported magazines do not benefit from investment capital. Parachute may have the potential to attract private investors, given its wide international impact and the quality and specificity that are generally associated with it. If we could launch fifty thousand copies on the market, this would change the game, and we could become independent. After all, even with a low average print run of four thousand copies, we were distributed in forty countries! In any case, we have nothing to gain when it comes to Canadian grants to periodicals (which we have definitively rejected); the programs now in place clearly favour local magazines with local content and a small print run. There are no programs for international distribution or export. In any case, it must be realized that exporting is also a question of content and that it is not enough to be visible only abroad; we have to be able to attract readers internationally, raising relevant debates and questions, and to participate in the issues that animate the international scene and not just the Canadian one. With Parachute, I always tried to create a dynamic between us and the international scene, to contribute a form of specificity based on our dual culture and on a vision of the world built from that, built also on my own hybrid nature on the level of my artistic and intellectual education, based on the mixing of languages, intellectual disciplines, and art forms.

To close, in relation to the philosophy behind Parachute, the desire to change the game, to open up our situation, to transform dynamics (a basic political role, in short), I do not see myself continuing Parachute “the magazine” without accompanying it with an event. This is what we did in the early years of the magazine, and it seems important, at a time when there are fairs and biennials all around us – all of them rather similar – to place the issues that Parachute raises back in the field. It’s a plan that I have and that may play out in interventions here and there on the international scene through an event – a means of interaction – for which the magazine could be the main tool of reflection and development.

Translated by Käthe Roth