by Petra Halkes

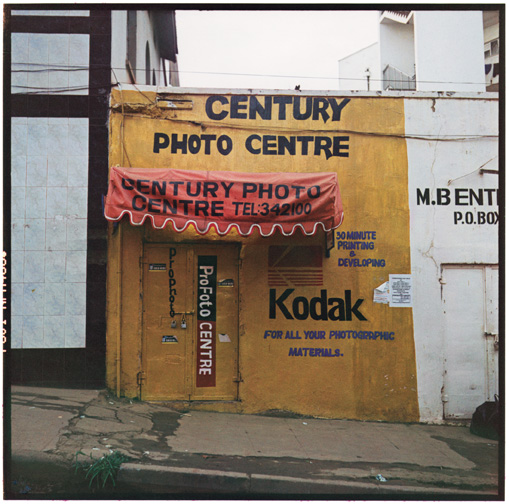

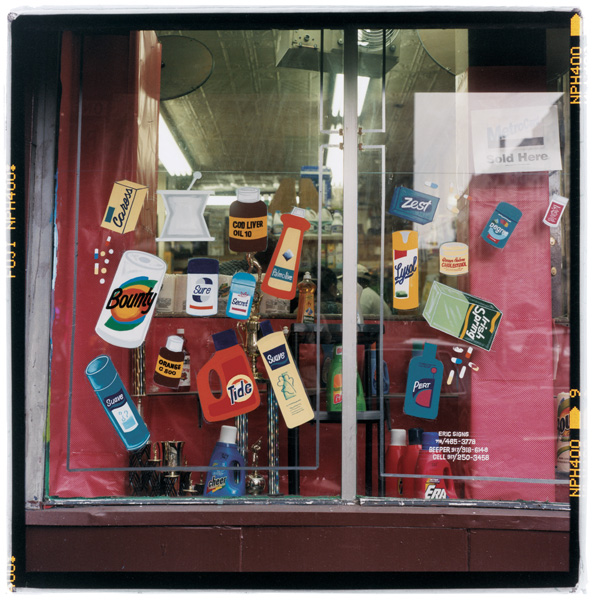

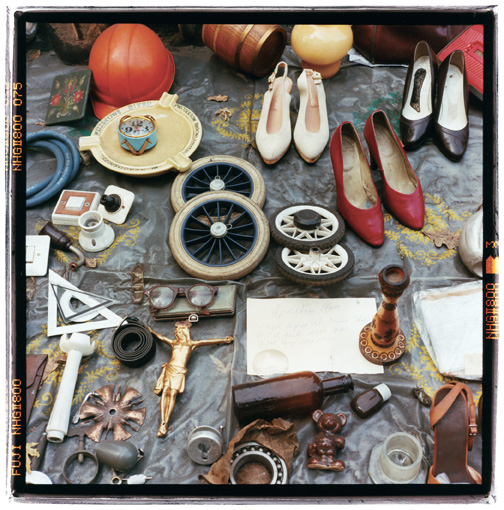

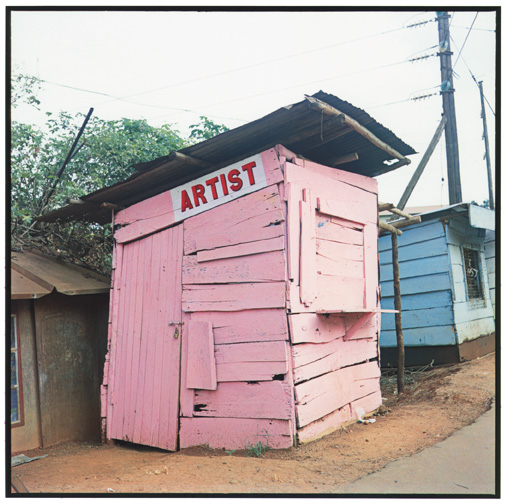

Using the unflagging documentary power of photography, Zoe Leonard lends us her eyes and shows hundreds of small business operations – discount stores, repair shops, restaurants, and flea markets – and the everyday objects associated with them.She began the project, Analogue, in her home city of New York, where she photographed storefronts in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Then, journeying to cities as distant as Jerusalem and Kampala, she captured similar neighbourhood shops and the omnipresent multinational brand names in them. Shot between 1998 and 2007, the images of struggling small businesses in different cities of the world began to show the flow of consumer goods from poor to rich countries and back again.

Intrigued by the huge bundles of used clothing that she had photographed in Brooklyn, Leonard followed the trajectory of clothes that are donated for charity to wholesale dealers and local market stalls in developing countries. Garments – most likely sewn in poor countries for pennies apiece–are seen in bargain bins at New York sidewalk sales, and then again as second-hand clothing in another poor country.

In a New York photograph, dozens of new shirts on wire hangers are pressed tightly together on a rack that sags under their weight. Farther along, in an image shot in Brooklyn, we see a huge bundle of used clothing that is marked “892 SHIRT’S” [sic]. The bundle reappears on a hand-painted sign of second-hand clothing importers in Kampala, Uganda. Finally, we see used shirts, carefully protected from the sun and artistically displayed, in photographs of street markets in Kampala.

Glamorous shopping malls and cost-efficient big-box stores are noticeably absent. By aiming the square viewfinder of her vintage Rolleiflex frontally and up close, the artist draws us in to these small, threatened worlds. Shuttered storefronts, dilapidated buildings, and signs announcing final sales intensify a sense of transition and loss in the face of increasingly globalized industry and trade. Analogue impels us to think about the meaning that local shops and their care-worn commodities provide in our lives.

Edited down to a generous four hundred C-prints and gelatine-silver prints, Analogue was exhibited last year at Documenta 12, and at the Wexner Centre for the Arts at Ohio State University. A handsome catalogue, co-published by the Wexner Centre and MIT Press, presents a third version of the work, in which eighty-three images are scaled down to seventeen centimetres square from their exhibition size of twenty-eight.

Created in a period of increased offshore production and global trade, Analogue mourns the loss of concrete interactions between people and commodities, which are dissolving in the abstraction of mega-systems.

A desire to hold onto things pervades the project. Created in a period of increased offshore production and global trade, Analogue mourns the loss of concrete interactions between people and commodities, which are dissolving in the abstraction of mega-systems. Objects not only sustain and protect our physical beings, they help us create meaning in our lives. We relate to each other through objects, we think through them, express ourselves through them; we form our identities through the interaction with the things that surround us. Leonard has consistently demonstrated a deep awareness of the role that objects play in providing a sense of who we are. When at times she seemed unable to find anything out there in the world that could reflect her particular sense of wonder, indignation, or passion, she created new objects. After the death of a friend, she began sewing dried skins of fruit back together again, adding buttons, wires, and zippers. Begun in 1993, this work, titled Strange Fruit (for David) had grown to three hundred pieces by 1998.

Commodities that have been created or harvested by people directly, without too many intermediary processes by machines or mega-systems, are invested with a human spirit, which makes it easier for us to see ourselves reflected in them. Mass production works against a direct, personal involvement with the production and distribution of commodities. Walter Benjamin, writing in the early twentieth century, noted, “The commodity has become an abstraction. Once it has escaped from the hand of its producers and is freed from its real particularity, it has ceased to be a product controlled by human beings. It has taken on a phantom-like objectivity.”1 In the twenty-first century, the abstraction of commodities has increased: industry and commerce are relegated to mysterious apparatuses in mega-production and trade systems.

Analogue presents objects and settings that struggle to escape this abstraction. It gathers commodities that are animated with a human presence, allowing us to recognize ourselves in them. Appliances, furniture, clothes, household items, and electronics have been marked by hand, repaired and recycled, in these small business establishments. Some, such as the pressed-board closet and computer desk, have dropped out of mass shipments to become surplus. They find themselves holding their own, individually wrapped in plastic, for sale on a Brooklyn sidewalk.

By using analogue photography, Leonard draws an analogy between its demise and the obsolescence represented in the photographs. The loss of analogue photography’s tangibility – its negatives, darkrooms, and prints – to the ephemeralness of digital photography is seen as part of a more general abstraction of daily life.

Like the analogue camera, the catalogue, a hardcover book, is another threatened object. The intimate “thing-ness” of the book helps the viewer to move from a nostalgic appreciation of picturesque storefronts and hand-painted signs to a more philosophical contemplation on the role of concrete objects in the creation of meaning; we grasp the cover and turn the pages, all the while looking and thinking. Even Leonard’s catalogue text – existing entirely of quotations, things taken out of books and transformed by a new context – can be considered a compilation of objects. Her desire to preserve things shows in the cover of the book as well; it is made of Buckram cloth, which is used by libraries to rebind worn volumes.2

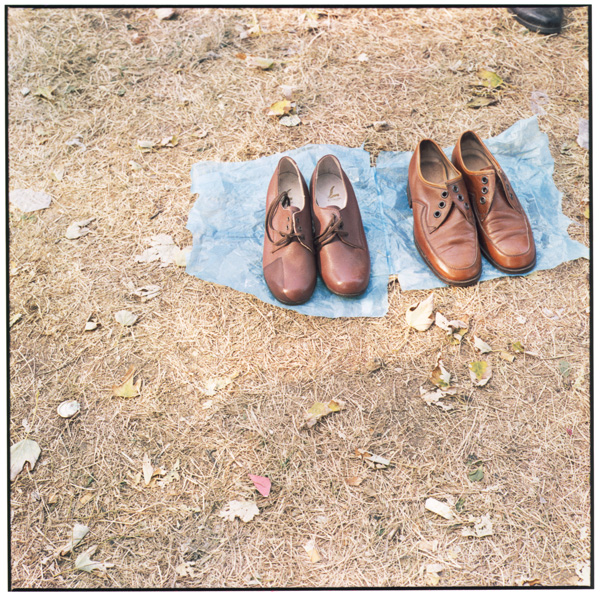

While Benjamin analyzed mass production of the early twentieth century as it had evolved from the industrial revolution of the nineteenth, Analogue shows that in the twenty-first century, the ongoing and increased abstraction of industry and commerce has still not eradicated people’s desire to create, handle, and order things in their immediate environment. It also shows that hope for the persistence of direct agency and interaction with objects has decidedly shifted to poorer countries. In contrast to the bundled clothes and closed-up shops in New York, we find the most humble and tattered things displayed like treasures on mats and racks in Eastern Europe or Africa. A photograph taken in Warsaw shows two pairs of brown shoes, carefully placed on a plastic bag that is cut open and spread out over a patch of dried grass. One pair is worn and without laces. The other is new; there are no creases, and no feet have yet erased the brand name on the inside sole. But the right shoe has an odd, triangular patch of darker brown leather on its side, as if someone tried to repair a manufacturer’s defect. The seller, or a prospective buyer, is nearby; we can just see the tip of his shoe in the right upper corner. Perhaps this photo, the last picture in the book, is an invitation to walk in the shoes of the poor, away from the abstractions of life in an overwhelming consumer culture.

1 Cité dans Susan-Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1999, p. 181. [Notre traduction.]2 Sherri Geldin, “ Directors’ Foreword,” in Zoe Leonard, Analogue (Columbus, Ohio/Cambridge, Mass., Wexner Center for the Arts/MIT Press, 2007), p. 2.

Petra Halkes is an artist and writer. She is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, and her book Aspiring to the Landscape was published by the University of Toronto Press in 2006.

Zoe Leonard, a New York multidisciplinary artist, has been active on the international art scene since the late 1980s. Her artistic production has oscillated between sculptural installations in gallery settings and photographic works. The Analogue series was initiated in New York, and later continued in Jerusalem and Kampala. In 2007, it was exhibited at Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany.