by Jean Gagnon

Since he began his photographic practice, George Legrady has been interested in the fate of images and their detachment from the “real,” first through strictly photographic methods, then, starting in the mid-1980s, through digital techniques. Images produced during various times of his career, as well as certain images taken from his interactive works, were recently on display at the Pari Nadimi Gallery in Toronto.1 One of Legrady’s latest installations, Cell Tango: Global Collaborative Visual Mapping, gives me the opportunity to look back at his career. One of the pioneers of intensive use of computer technology in the context of an art practice, he is now a professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, where, as an artist, he may also pursue scholarly and technological goals. Although his basic impetus is artistic, Legrady, like a number of his colleagues, has shaped his research to explore the capacities of data-management and -exchange systems, new possibilities offered by information technologies.

Legrady was born in Hungary, but he began his art career in Montreal, and his working tool was a camera. Studying at Loyola College, Legrady met a professor, Charles Gagnon, who was to influence him and point him toward a more conceptualist, even analytic approach to photography. The images that he produced at the time in the Found Objects (1976) and Floating Objects (1980) series, were marked by the spontaneous decoupage that his technique produced (here, the camera, the snapshot, the flash), which cut out and extracted first objects, and then the images themselves, from their referential context. The floating objects, for example, were found in construction sites at night; Legrady threw them into the air in front of himself and shot them with a flash; the result was an strange abstraction, neither beautiful nor revealing, simply objects detached from the “real” – a forerunner of what digital works were to do even more emphatically – that is, the delocalized image itself could become the object of hyper-indexing that places it in circulation through computerized semantic and syntactic systems in which language plays an important role.

Thus, Legrady’s photographic practice quickly led him toward an aesthetic of detachment and delocalization; later, using computers, he developed an aesthetic of images in transit, a hyper-mediation through which images find meaning through contact and interconnection with other images. In the 1980s, Legrady questioned the photograph as evidence, document, or proof. He took a radically different path, into timeless non-place of photographic material and gesture; by fixing the images of objects in this inchoate eternity, he slipped awy from the aura of the “decisive moment” that haunted photography. Through his manipulations of images, he adopted a postmodern posture in which images are simulacra open to the play of indexing, delivered to the play of language.

Legrady’s images – those that he created through photography, as well as those that he found circulating in the media sphere and incorporated into his work – are thus detached from their referential contexts, but they gain in virtuality and circulatory velocity. In the interactive works for the 1990s, especially An Anecdoted Archive from the Cold War (1994) and Slippery Traces (1996), he began to use databases with which viewers, promoted to participants, could play. Viewers navigated the databases as one would navigate a river, reconstructing journeys and drifts, landscapes and riverbanks. In the most personal, the “anecdoted” archive, he placed two media horizons – that of the capitalist West and the communist East – face to face in a profound reflection on the relationships of a historical Subject and the imaginary horizons that surround and inform him or her. This “anecdoted” archive is one of his less analytic and most narrative works, but it is a narrative without narrator. The database plays the role of organizer, allowing a new path to be created each time, ordering afresh the discordance of images into a concordance for the user.

Through his manipulations of images, he adopted a postmodern posture in which images are simulacra open to the play of indexing, delivered to the play of language.

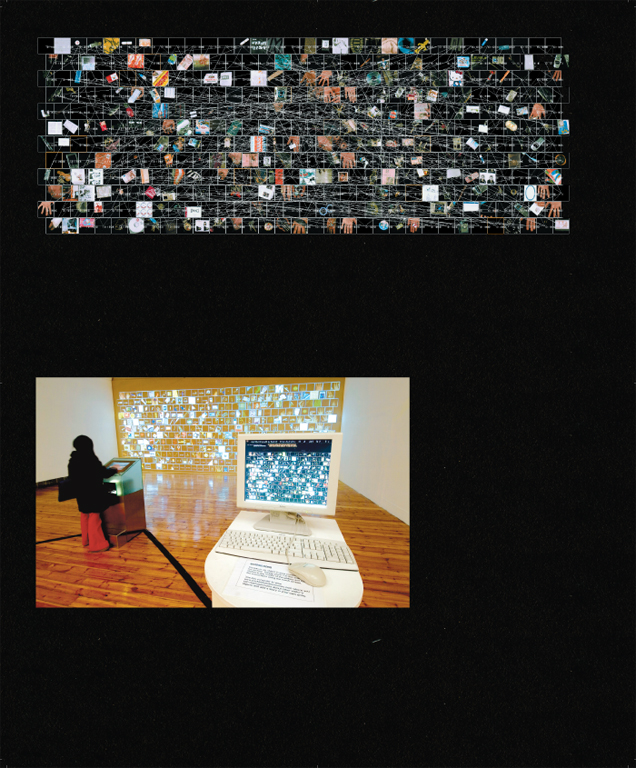

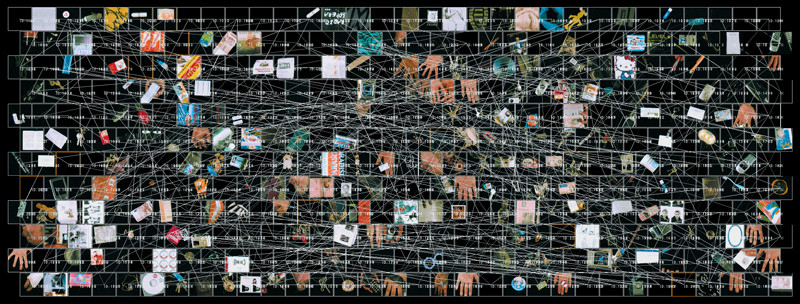

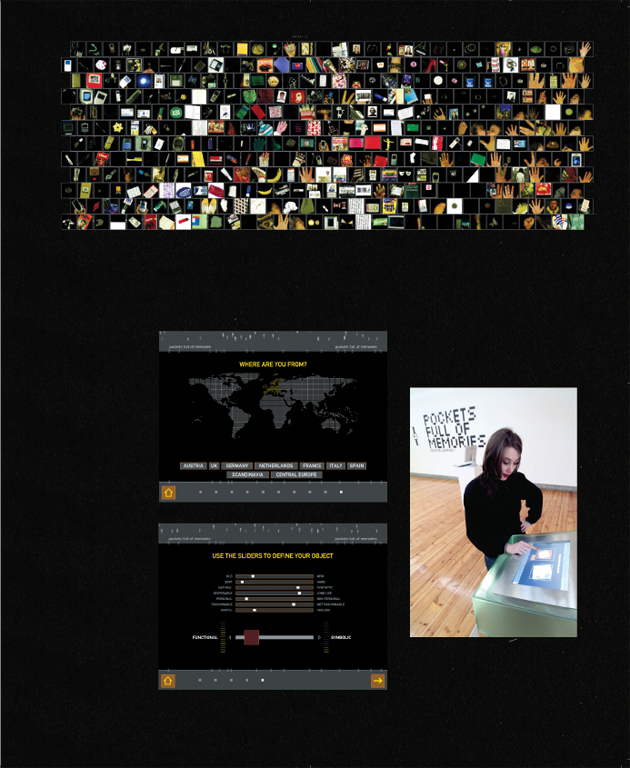

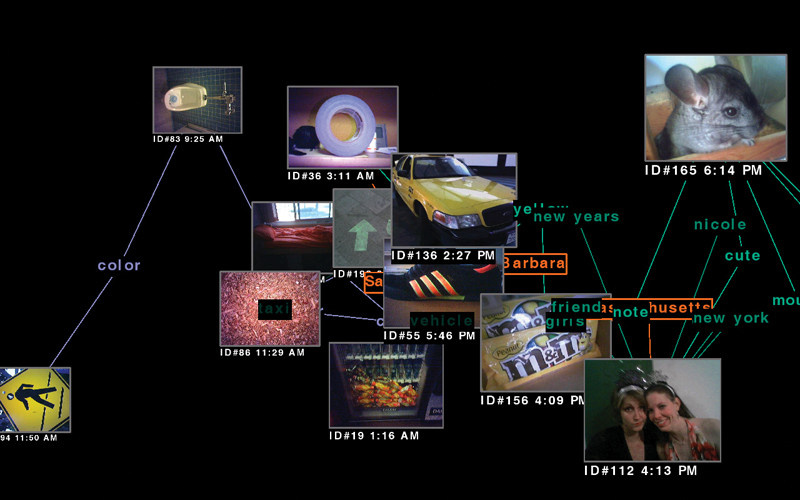

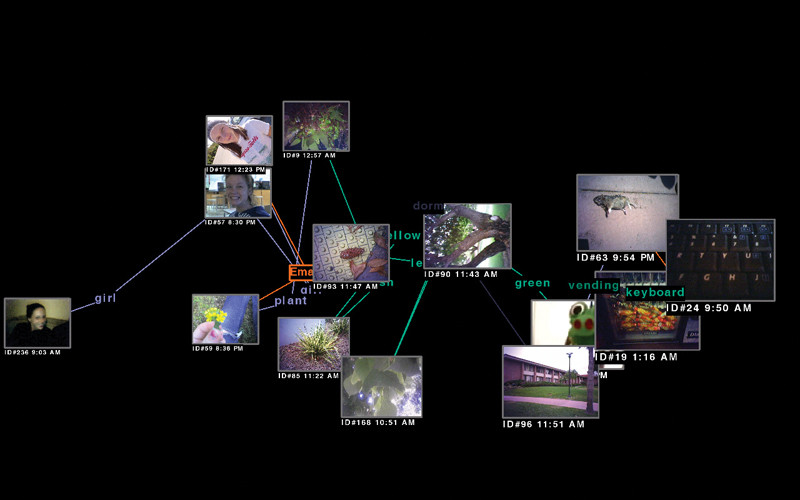

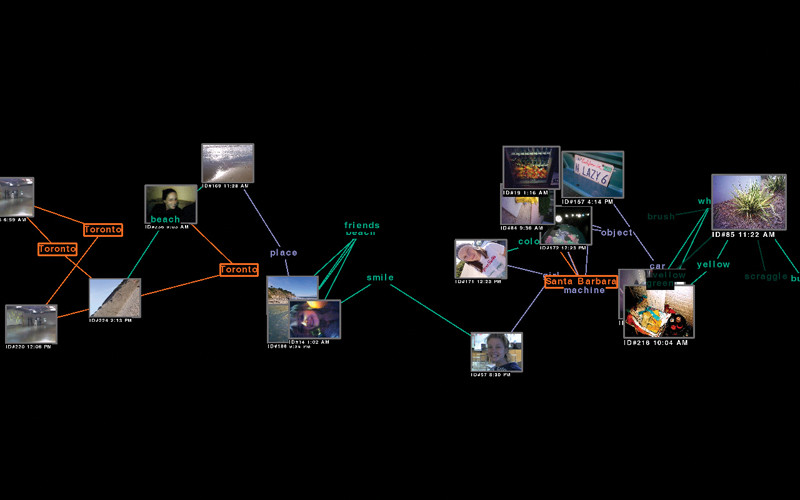

With Slippery Traces, Legrady returned to the distance that characterized his relationship as author with the work, and he left visitors to navigate in a database of postcards and create links between the images the principles of which could nevertheless remain subjacent. As Tim Druckrey wrote, “The underlying structure of Slippery Traces is based on a sort of theorization of the databank perceived as immanent signification.”2 In Legrady’s works, this is where the the metadata arise, indexing and linking the objects in the database and making it impossible to lock in beforehand any combinations, courses, or potential unique readings. Whether principles of transivity of images rest on proximate shifts in the workings of the unconscious or are explained by other means, they are here caught up in the toils and games of hyper-indexation. This trend has gained momentum in Legrady’s most recent works, from Pocket Full of Memory (2003–07) to Cell Tango (2007).

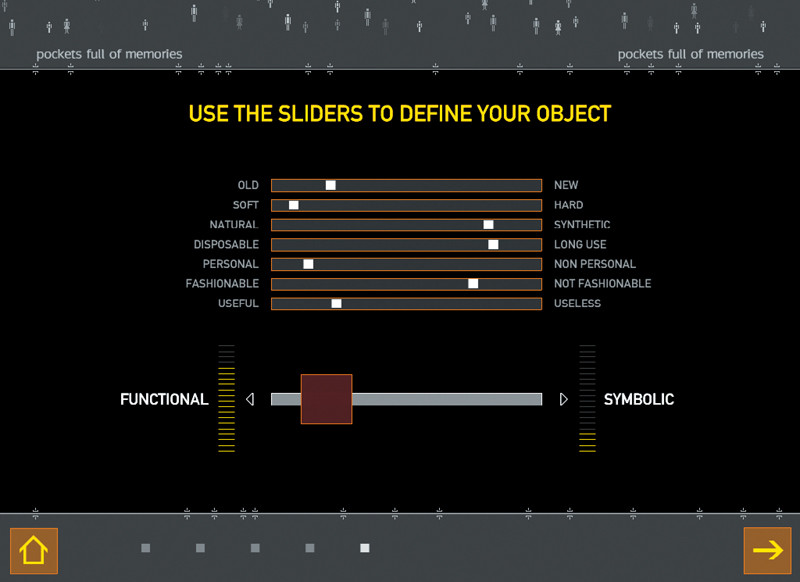

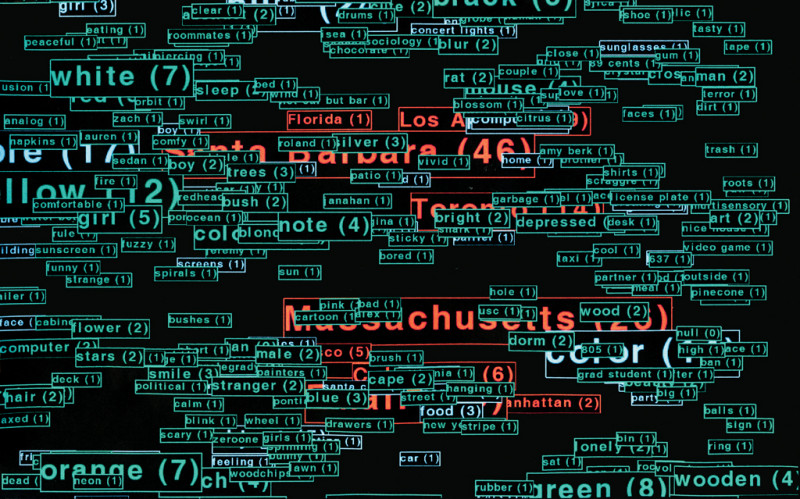

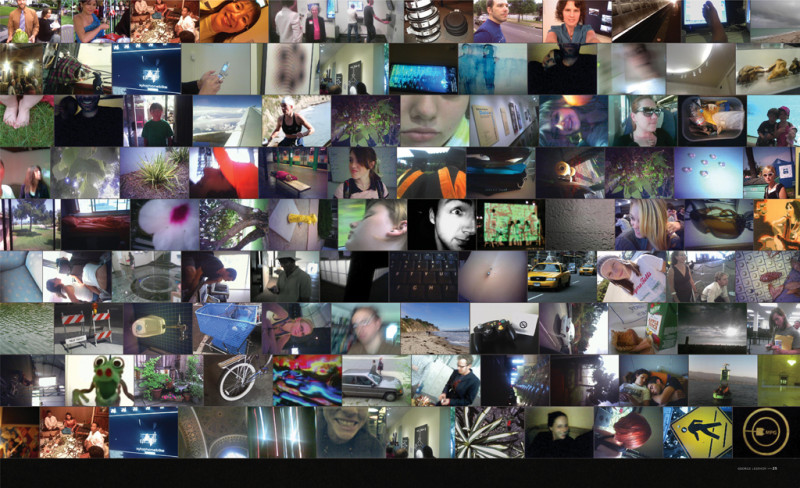

If Legrady is concerned with narrativity in his Archives, in most of his other works his interest is not so much in the stories that surround images but in the semantic layer that orders relations between the images. Yet, these relations take a less narrative and more indicial turn: words, tags, and taxonomies that users contribute do not so much participate in a Web hyper-narrativity as provide a different type of anchorage to these images, sounds, and texts in transit, the impact of which remains to be measured – the tangles among symbolic, functional, and real (practical) levels of information-management systems in the arts and culture fields. In other words how can the relationships between users and all of these images be described? What is its aesthetic?

Like a number of other artists, Legrady is now investing this non-place of cyberspace, this nimble image-transit space-time. He is exploring its cultural and social dimensions through mobile telephony, with its capacity to transmit images that people all over the world are making. By exploring the management system for these photographic data, by permitting “tagging,” by opening to a “folksonomy,” by tracing images through metadata such as time or place of transmission and IP address localization, Legrady is most interested in making “the invisible visible” – an expression that he borrows from Paul Virilio and that defines his analytic position.3

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 George Legrady, David Rokeby, Rhonda Weppler & Trevor Mahovsky, and Jennifer Stillwell – group exhibition, January 19 to February 23, 2008.

2 http://www.fondation-langlois.org/legrady/f/textes/druckrey3.html, p. 8.

3 July 2008. 3 In 1997, when I was curator of media art at the National Gallery of Canada, I produced, with Pierre Dessureault of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, a retrospective exhibition on George Legrady’s work. At this time, we published a CD-ROM catalogue designed by the artist. It is now available on line through the Fondation Daniel Langlois: www. http://www.fondation-langlois.org/legrady/.

Jean Gagnon is a curator and art critic. Recognized as a specialist in video art in the 1980s, he has been most interested in the intersection of art and new technologies. He became director of SBC Gallery in Montreal in 2008. From 1998 to 2008, he was director of the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology. From 1991 to 1998, he was curator of new media at the National Gallery of Canada.