[Fall 2008]

Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

March 29 – April 26, 2008

Intimate Strangers could be seen as a revisitation and continuation of a world of documentary exploration that began thirty-five years ago for Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas, with her Carnival Strippers project. Carnival Strippers came about when Meiselas attached herself to a “girl show” traveling through New England in the summers of 1973, 1974, and 1975. “The recognition of this world,” Meiselas wrote in her introduction to the resulting book (New York: Noonday, 1976), “is not the invention of it. I wanted to present an account of the girl show that portrayed what I saw and revealed how the people involved felt about what they were doing.”

This she did superbly. She then settled into a long and heroic sojourn in award-winning front-line political documentary practice that resulted in books (and related films) such as Nicaragua, June 1978–May 1979 (1981), her editing of El Salvador: The Work of 30 Photographers (1983), Chile from Within (1990), Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1997), and Encounters with the Dani (2003).

It might well have seemed, therefore, an odd circling back to a consideration of the imperatives and the ambiguities of the body and the modalities of desire when, in 1997, Meiselas produced Intimate Strangers. This was another kind of front-line reporting. Here, in what was an almost lasciviously thorough exploration of hitherto private fantasies, and working with the hot, lurid, interior kind of colour that film director Bernardo Bertolucci once referred to as “inter-uterine,” Meiselas documented life in a up-market S&M club in Manhattan called Pandora’s Box, a club that is apparently known, affectionately, as the “Disneyland of Domination.”

The project was originally commissioned as a photo-commentary adjacent to a documentary film by British filmmaker Nick Bloomfield (Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam [1995] and Aileen – The Life and Death of a Serial Killer [2003]) called Fetishes. The book of Meisela’s photos, boxed and heavily laden with interleaved sheets of “Lee colour-filter mirror silver 271,” “Caliper 1 mm. natural rubber grade S,” “Polyurethane-coated 100% polyester interlock,” and other matrices of artificiality, was published by the German firm Trebruk in an edition of 1,650 copies.

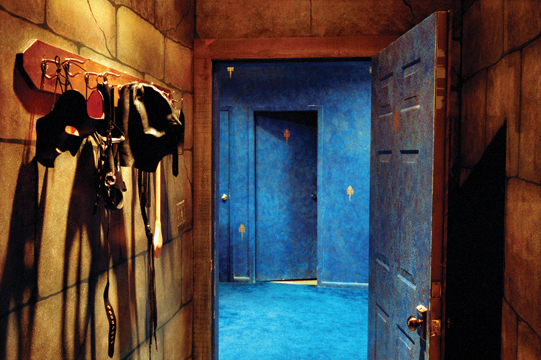

Meiselas gets in close – as she always did in the field. The Bulger exhibition, which featured a generous selection of the Intimate Strangers photographs (all printed in 2008), effectively walks the viewer through the Pandora’s Box narrative, beginning with a positively medieval-looking shot of the “Dungeon,” a sort of gothic locker room with a strange assortment of lace-on, padded restraint devices hanging from coat-hooks, all of which look eerily reminiscent of the masks and vests worn by baseball catchers. This leads – logically, one supposes – to a photographic encounter with a comely but clearly world-weary creature clutching an almost-empty coffee cup, who seems to represent what Meiselas has identified as Pandora’s Box: Reception II. The viewer is then admitted, photographically speaking, to the dramatic centre of the Pandora’s Box enterprise: the transactional S&M intercourse between client and sex-worker, between dominated and dom-inatrix. So poignant is Meiselas’s Pandora’s Box, Awaiting Mistress Natasha, The Versailles Room, with the naked male client kneeling on a florid floral carpet in the middle of an absurdly kitschy, faux-elegant drawing-room, so vulnerable and strangely baby-like is he, that the photograph offers a sad tenderness rather than any hint of voluptuous impropriety.

But, as Count Leopold von Sacher-Masoch dutifully reported in his novel Venus in Furs (1870), “In love, there is always the hammer and the anvil.” And being a hammer is hard work. The finest, most troubling, most touching photographs in Intimate Strangers are those that have to do not with fearsome bristling masks and headdresses or high-laced boots and the brandishing of whips, but with post-punitive exhaustion. Meiselas’s Mistress Catherine after the Whipping I, The Versailles Room is emblematic in this regard. Mistress Catherine, having dropped heavily into an ornate chair (in this relentlessly ornate room), appears to be asleep. Still laced into her thigh-high silver boots, she dozes beneath a big, awful, ersatz-historical painting of heavy, lush female nudes, flanked, as if she were a queen in her throne room, by carved plaster pedestals. And here is the telling detail, the punctum, as it were, of the photograph: resting on the pedestal to Mistress Catherine’s right is an hourglass, its sand almost all run out.

Toronto writer, critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author, of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe and Mail.