[Fall 2008]

by Zoë Tousignant

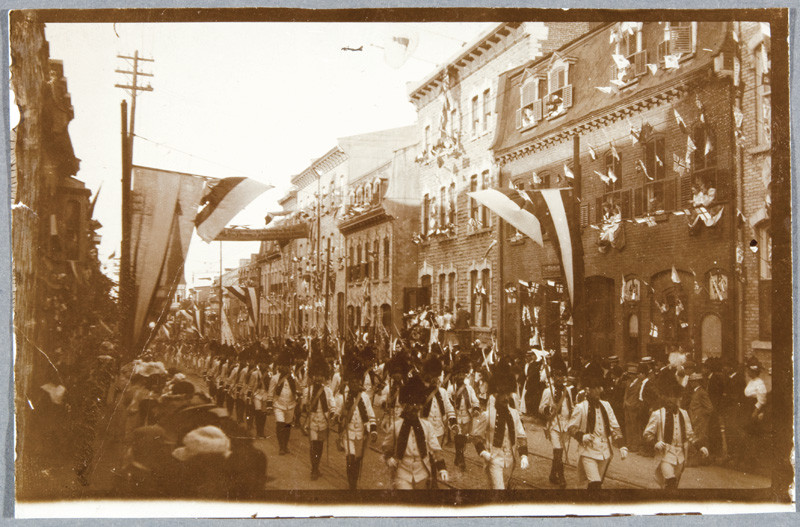

From September 25, 2008, to January 4, 2009, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ) is presenting Quebec City and its Photographers, 1850–1908: The Yves Beauregard Collection, the first extensive exhibition of early Quebec photography to be organized by the museum in over twenty years. Quebec City and its Photographers, which brings together more than 250 images – ranging from early daguerreotype portraits to documentary photographs of Quebec City’s tercentenary celebrations – is, moreover, the only historical photography exhibition mounted by the museum to consist entirely of items from its own collection.

Acquired in 2006 and comprising 3,540 objects, the Yves Beauregard collection is the largest group of photographs ever to have entered the MNBAQ’s main holdings (in fact, thanks to its acquisition, the photography collection has quadrupled in size). The collection was amassed over a twenty-year period by historian Yves Beauregard, a process that was concurrent with and undoubtedly informed by his role as editor-in-chief of the history magazine Cap-aux-Diamants. Reflecting Beauregard’s love affair with the town he calls home, the collection has a definite focus on Quebec City; while photographs made in Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Rimouski, and elsewhere are part of the mix, representations of the streets and inhabitants of the Old Capital form the bulk of the collection.

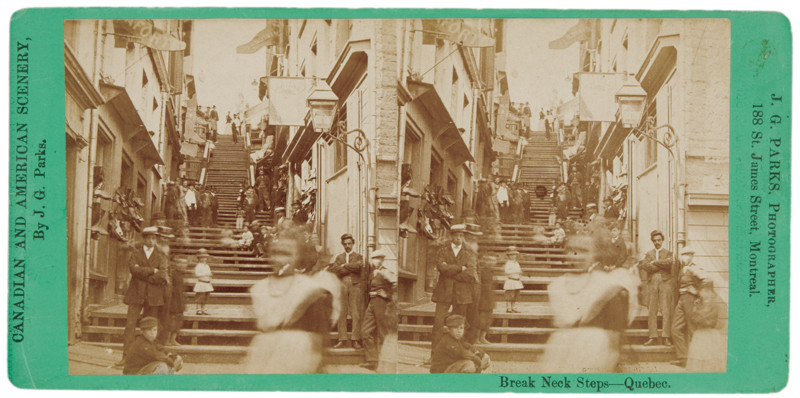

The objects included are representative of the array of genres popular between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chief among these are studio portraits, in both carte-de-visite and cabinet formats; views of the city’s architectural landmarks, made for sale to tourists and locals alike, mainly in the form of stereographic cards; photographic albums commemorating public and private events; and large-format composites recording for posterity various civic institutions or community groups. Taken as a whole, the collection offers a unique insight into not only a vibrant chapter of Quebec City’s history but also the period when photography came of age as an industrial, democratic medium.

Taken individually, however, the images that make up the Yves Beauregard collection are not always so easy to assess. Indeed, the collection includes a great number of photographs that seem to elude or even disrupt some of the foundational art-historical concepts on which a museum of fine arts such as the MNBAQ rests. The concept of authorship, for instance – the pervasive idea that the figure of the artist is central to a full understanding of the meaning and relevance of art production – is crucial for the way the museum narrates the history of Quebec art (this can be discerned from the title of the exhibition, which closely echoes that of another show organized to celebrate the city’s 400th anniversary, Quebec City and Its Artists).

Although the Yves Beauregard collection boasts numerous outstanding works by Quebec City’s “greatest” nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century photographers, including George William Ellisson, Louis-Prudent Vallée, Marc-Alfred Montminy, and the successive heads of the Livernois family enterprise, these are outweighed – in number at least – by photographs that are essentially authorless. Within this crowded camp are the professional and amateur images that, being unsigned, are literally authorless, but also the ones made by lesser-known photographers – those to whom history has not been kind either because their talent was less than outstanding or, more probably, because they operated at the lower end of the economic spectrum.

the collection includes a great number of photographs that seem to elude or even disrupt some of the foundational art-historical concepts on which a museum of fine arts such as the MNBAQ rests.

This last statistic is one that careful and laborious research may rectify (an effort has already been made to identify some of the innumerable portrayals of male and female members of the Catholic church), but for the moment what we are left with is a large body of portraits whose subjects are mute.

These scores of faces are unknown, yet at the same time they are strikingly familiar. They conjure up those that fill our old albums and shoeboxes, stashed away in attics or displayed lovingly on bookshelves; they are my great-grandmother’s sister, who gazes sternly out of the carte-de-visite portrait taken on the day of her engagement; they are my great-great-grandfather, captured in an intimate tintype portrait with his best friend, both dressed to the nines and holding cigars, that has always been the subject of family speculation; they are my grandmother’s snapshot of a gathering on a rainy day in Quebec City, which mysteriously still takes pride of place in her family album. There are countless photographs just like these throughout Quebec and beyond, proof of the repetitious, industrial character of photography. They are nothing special, yet for those involved they hold great personal value.

But what is the value of these images within the context of the MNBAC? Without the comforting foundation provided by authorship or even identity, what is the nature of their contribution to the history of Quebec art? An easy way out of this conundrum would be to avoid interpreting these photographs individually and instead treat them as parts of a whole; in other words, the author-function would be transferred from the individual images to the collection itself, which would take on the status of a work of art. In this scenario, Yves Beauregard, as the collection’s progenitor, would be the figure through which the body of photographs that bears his name acquire meaning.

Fortunately, it is unlikely that this option will ever become a reality, since respecting the internal integrity of collections-as-works-of-art is not common practice at the MNBAQ (Beauregard’s presence is, of course, still acknowledged, but only nominally). I say fortunately, because this approach would do nothing to explain the multitude of singular images that, though repetitive, deserve to be apprehended individually, nor would it do justice to the actual practice of photography in Quebec City in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The fact of the matter is that this practice was not dominated by a few outstanding photographers who produced a few outstanding images, but by a profusion of practitioners – good and mediocre – who were serving the photographic needs of the populace. The images that these practitioners made, as the Yves Beauregard collection shows, are the rule, not the exception.

What the Yves Beauregard collection represents is an opportunity for the museum that now owns it to investigate the true character of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century photography in Quebec City – in all its multifarious, populist glory. It is an opportunity to gain a fuller understanding of the local history of photographic seeing, and consequently to add a vital component to the non-media-specific, non-hierarchical history of visuality in Quebec. There is little doubt that the MNBAQ is well placed to carry out such a project. Whether it will remains to be seen.

Zoë Tousignant is a Ph.D. student in art history at Concordia University. Her doctoral research concerns the use of photography in popular Canadian magazines during the interwar period. In 2006, she worked as an archivist for the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec on the acquisition of the Yves Beauregard collection.