[Fall 2009]

par Maxime Coulombe

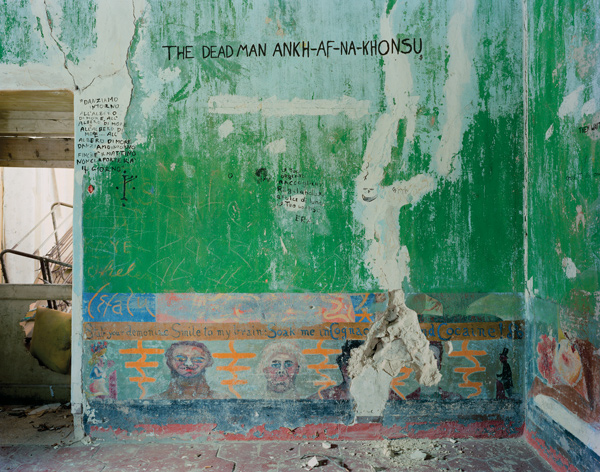

In 2005, Koester went to Celafu, Sicily, to find Villa Santa Barbara, a place once associated with the occult. Aleister Crowley, known in England for his membership in esoteric societies, established a secluded community involved in black magic and free sex there in the early 1920s. He gave the villa an apt new name: the Abbey of Thelema. The initiation rites that took place there involved experiencing the dark side of Eden by spending an entire night – probably drugged with opium and hashish – in the Chamber of Nightmares, a room decorated with frescoes depicting hell, heaven, and Earth inhabited by lewd demons and goblins. Mussolini shut down the community in 1923, after the death of one of its members drew the attention of the English media. The once-isolated house, abandoned, was gradually overtaken by urban development.

In his project Morning of the Magicians, Koester documents the search for this house, then records how time has altered it. Half- obliterated frescoes, dark stains on the walls, and deserted rooms indicate, as if by subtraction, a past that remains. The work of time gives this place an almost understood appearance – or, better, an expected resemblance, to use Blanchot’s term. What better fate, indeed, could there be for a centre of occultism than to see its ruin transfigured into a haunted house? We must pay attention to this “haunted future” of the Abbey, which indicates one of the paradigms of Koester’s photography. For, in the end, what is a haunted house if not a place bearing the weight of the events that took place there?

Imbued with occultism and an outmoded fin de siècle scent, the notion of haunting might bring a smile; yet, it perhaps simply defines the uniquely human capacity to make perception last longer than the perceptible. Think of it: a drama cannot be reduced to materiality, to the duration of its factuality; it seems to take root in space, to stick for a long time to the walls that beheld it, to still resonate in the air. For witnesses and victims, once the shards of safety glass are swept up and the sand spread on the asphalt has blown away, a street corner seems to bear for ages the traces of the car crash that took place there. For a director, an empty theatre, even fallen silent, may still vibrate through time with the emotions that roiled it.

We know that the visible is dependent on the material objects that shape it: as objects disappear and traces are erased, the visible dies, is forgotten. But what happens to the tragedy that still sweats from the roadway, the emotion still suspended in the air of the theatre? What is the duration of a phenomenon that cannot be reduced to the visible, to its materiality and details?

In The Kant’s Walk (2005), Koester photographed the place where Immanuel Kant took his daily walk. Kant’s life, dedicated to produc- tion of philosophy, was as carefully ruled as music staff paper. The philosopher’s walk, taken in solitary, following the identical path every day, is thus particularly interesting because it contributed to his philosophical thought. For an individual who left no diary and wished to disappear behind his work, this walk was thus, in its full sense, philosophical.

Koester sought to uncover this historic path. His little inquiry leaves us, however, far from a particular route, and thus far from an ideal philosophy, in the depths of a small town once named Königs- berg and now known as Kaliningrad – a town disfigured by the Sec- ond World War, then scarred by desolate urban development. In spite of everything, it brings to mind the thickness of time that has buried Kant’s wanderings and, especially, what the philosopher may have drawn from this landscape, today overwhelmed by the most depressing industrial decrepitude. Something of Kant may well still haunt this scene, and our gaze cannot help but seek the trace.

Haunting places, haunting images

“Events do not occupy the surface but rather frequent it.” – Gilles Deleuze1

A haunting makes a space, a simple neutral frothing-up of the visible, into a place – that is, a region invested with meaning and emotion. A haunted place bears the mark of an event that continues to endure and that, even invisible, gives presence to the space. It is if something unresolved in the event – even though long since wiped away – still ran through it.

Of course, that which haunts is not necessarily, not only, tragic. Misfortune is not alone in having the power to open space to longevity. It seems, on the contrary, that it is the specific density of an event that makes it too big for the place, the space, that contains it; thus it makes time its home. Beyond the materiality of the visible, the event continues to distil its effects, as if despite the visible. “I believe most human activities leave traces in space,” sum- marizes Koester. “In one way or another, spaces are transformed by human action, and in my work I am, if you like, ghost-hunting spaces.”22

An apparition seen by a single person is only a hallucination; it lives in the vertigo of subjectivity. The phenomenology of haunting involves – through a paradox that I shall have to explore elsewhere – a shared gaze. This type of phenomenology places us at the core of the construction of meaning, at the moment when meaning slides between the interstices of representation, even of the world itself, to bring it to life.

Thus, nothing is more uncertain than the appearance of a ghost, the anthropomorphization of haunting. It seems to manifest itself only to those who believe in it, those who believe in the capacity of an event to survive and be invisible. Haunted places do not become fascinating – grabbing the eye, providing a detour from one’s route, a pretext for a search, or even a reason for a trip – except when someone lends an ear, opens an eye. A place is haunted only to the point that some curious person ventures to cross the threshold of a site that is abandoned, devoured by oblivion.

Superimposing layers of time – that when the picture was taken, that of the gaze, and, in Koester’s case, that of the event – the photograph forces us to remember that the present is a sedimentation of temporalities.

Koester’s works await these curious people, those who are usually called, in the art world, viewers. This is why, like the rumours surrounding a haunted house, which endow it with the troubled aura that conditions perception, Koester leaves in the margins of the photographs some documents, traces of the epoch, or paths. Plans of Kant’s route traced on period maps, texts describing the history of Crowley’s community, bygone objects – these bits of information change our viewing of the image into a strange exercise of memory. It is up to us, the viewers, to breathe new life into this almost-forgotten memory, to make it live on the surface of the photograph.

The haunter, the ghost, needs a public to express its phenomenology. This is why Koester’s art production is not just the private affair of an adventurer of the invisible who hangs absurd, emptied traces of his improbable expeditions on gallery walls and hopes that view- ers will be fascinated by them. Like a child who hopes to catch the flame of a lighter with his hand. Like a child, his hand burned but clenched, suddenly opens it, hoping to re-create the fire in his cupped palm.

The haunting is that strange sensation of burning. Thus, to re- create it, it is important to set the conditions of possibility of this flame, then leave viewers to bring their hands to it. Koester simply shows, in what some consider to be conceptual photography, the urban chaos of Kaliningrad or the blind walls of Villa Santa Barbara. It is up to the viewer to invade these spaces of emotion, desire, visions. It is up to the viewer to raise the phantoms.

Revealing the haunting

The most precise technology can give its products a magical value, such as a painted picture can never again have for us.

– Walter Benjamin3

In Message from Andrée (2005), presented at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris as part of the exhibition Five Billion Years, Koester showed a video montage of found photographs of the expedition to the North Pole undertaken by the explorer Carl Auguste Andrée in 1897. The explorer’s party, travelling by hot-air balloon, crashed very close to the Arctic Circle. Without a way to get back or any form of communica- tion, the expedition’s members fell to the cold one by one. Years later,traces of this tragic epic were found, including photographs eroded by the cold and in various stages of degradation. These images – reworked, reframed, “cleaned” – have often been exhibited since the 1940s. They show the different stages of the expedition, the crash sites, the encampment built to stave off the cold, the blank landscape.

Koester selected the rawest photographs, the ones most rarely shown, those most damaged by degradation: abstract images, covered with stains, blank spots, and snow. He made a montage of them for a film that is abstract and yet constitutes the final traces of the tragic expedition. The photographs, taken by men who knew that their death was imminent, are testaments, addressed to a hypothetical viewer. Behind their illegibility shines the burning question: “What happened?” These abstract images are fascinating because the event that they aspire to portray cannot be prevailed upon to appear. They are “[t]he invisible index of things,” as Koester brilliantly puts it.

The history of the supernatural is populated with the strangest, most absurd apparatuses, whose purpose is to give a glimpse, to reveal the existence, of the invisible. They have in common that they function in the system of the trace, the imprint: complex machines that perceive tiny vibrations of the ether, gramophones of ghostly breaths, electrograms of ectoplasmic energy, but above all, and in a constitutive way, cameras.

Photography is in some way related to the invisible. It may be the site, the surface par excellence, for its appearance. Since Balzac, the photographic image has been suspected of doing much more than copying the surface of the visible, but actually seizing it, snatching it, capturing it. Balzac believed that whenever a picture was taken, the image took away, irremediably, an intangible part of the photographed subject. It thus touched something beyond the visible and, as an instrument that immobilized the world, it was able to seize the evanescent.

If the visible possesses some complexity that the human eye cannot grasp, if photography, by immortalizing the visible, performs an action of which the eye is incapable, it is legitimate that some may have believed that the perfect medium for the invisible is the photo- graphic image. Floating on the surface of the image, the gaze often believes it. Superimposing layers of time – that when the picture was taken, that of the gaze, and, in Koester’s case, that of the event – the photograph forces us to remember that the present is a sedimenta- tion of temporalities. And thus, the photograph, underlining the coa- lescence of temporalities by allowing us to see them, does not belong solely to a Barthesian “that which was” thought of as mourning and distancing. It involves also, through this distancing, an opening to what remains, what survives of the past. In other words, what haunts and gives “that which was” its emotional power.

Koester is but a modest “ghost hunter,” one of those hunters who leave their gun at home, preferring to take a few friends and show them the simple moment, both simple and disturbing, of the rising. The brief moment when the visible shudders and the space opens up, when the unexpected emerges from the shadow and then, for the better, the instant after, sinks back in.

Just under the skin of Koester’s photographs lives a buried layer of time that, though invisible, alters the representation. These images, and the regime of the gaze that they offer, reminds us that we are far from finished with haunting.

Translated by Käthe Roth

3 Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 1931– 1934 (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 510.

Maxime Coulombe, a sociologist and art historian, teaches contemporary art at Université Laval. He recently published Imaginer le posthumain: sociologie de l’art et archéologie d’un vertige (Presses de l’Université Laval).