[Fall 2009]

by Adam Carr

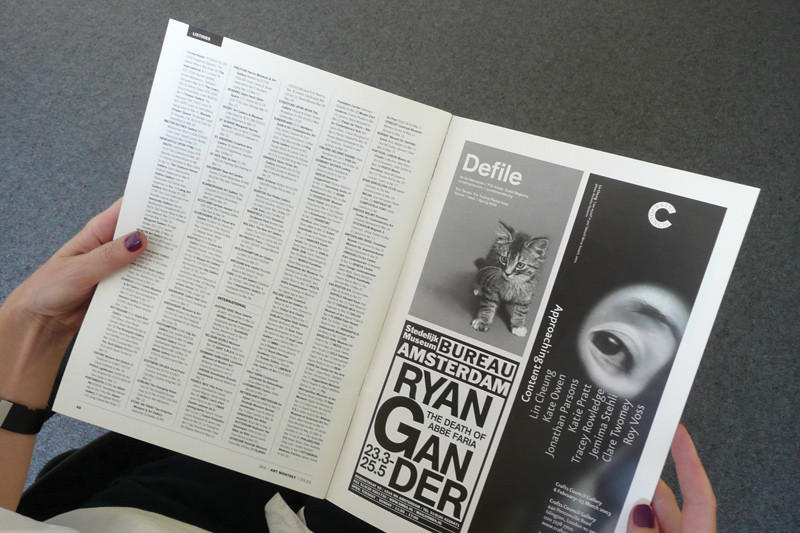

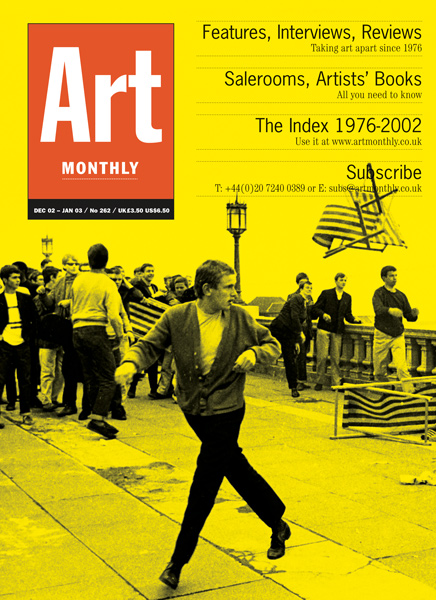

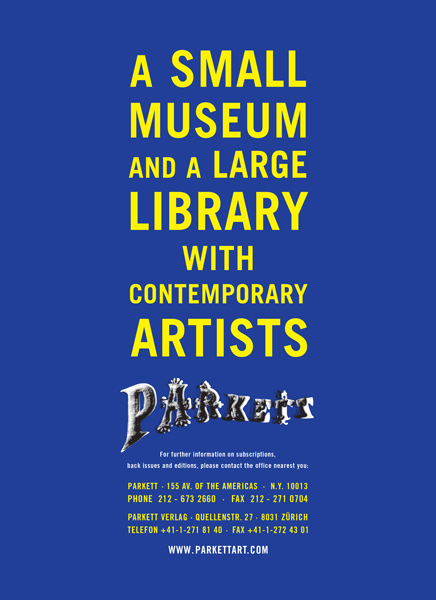

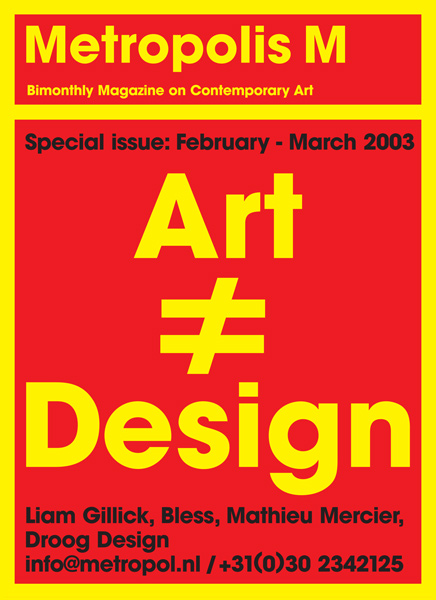

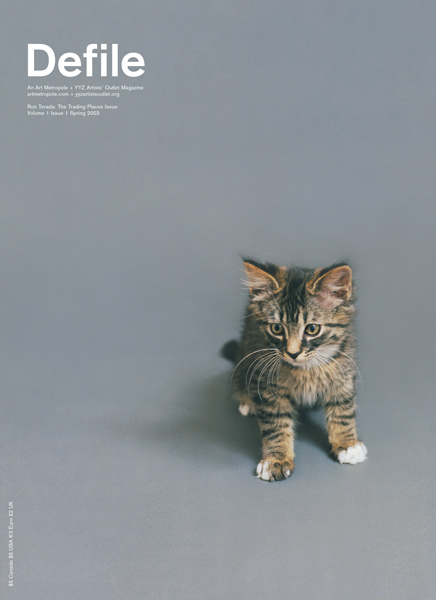

At first glance, the work Defile (2003) by Vancouver-based artist Ron Terada seems to be a standard magazine, bearing all of the hallmarks synonymous with art publications. It has front and back covers, a title, and, at 11″ by 8″, a standard sizing – even an issue number, suggesting that more issues will follow in the future. We could be forgiven, when looking at its content, to assume that it is one art publication among the many currently in circulation; it is full of advertisements. Although we know that art publications contain editorial content, when we flip through them at the news-stand, we find it increasingly difficult to pinpoint where this content actually lies. This is due, in part, to the ever-increasing need for advertising, which pays for production, staff, and contributors. In the case of Defile, however, when we look a little closer, it becomes apparent not only that advertising space comprises the magazine’s entirety, but that in fact advertising – or, perhaps more correctly, the idea of advertising – is its principle subject and main focus. Each page contains the front-cover image of an art publication. Yet, it is the second part of the work – which exists literally outside of the magazine – that provides the key to a full understanding of Defile’s operation and, in turn, reveals its conceptual simplicity. Terada requested that each magazine advertising in Defile should run the front cover of Defile in its pages, as an ad, in return. The trade-off that occurred saw the participation of such magazines as Artforum, Afterall, Flash Art, and Parkett, and a deviation from internationally recognized publications including Canadian Art, Camera Austria, and C Magazine.

The history of the magazine as a site for artistic expression, consciously considered by Terada or not, certainly provides a significant historical precedent here. Perhaps one of the first instances of the meet- ing of art and magazine – or the printed, publishing page – is La Révolution surréaliste, by surrealist figure-head Andre Breton, who released the first issue in 1924. Appearing sporadically between 1930 and 1933, the magazine was nothing short of revolutionary and lived close to scandal, as did the surrealist movement itself. For the twelve issues of its existence, the magazine was treated as a medium in which the very forefront of surrealism could ultimately be documented, including texts to and reproductions of artworks. A handful of surrealist magazines followed shortly thereafter, Acephale and Documents most notable among them. Some thirty years later, an example of the magazine as a format for artistic activity can be located in the seminal Art & Project bulletin, published between 1968 and 1989 by Adriaan van Ravesteijn and Geert van Beijeren, who ran the eponymous Amsterdam-based gallery. Although they initially utilized Art & Project as way to announce upcoming exhibitions in their gallery, their focus soon shifted toward the format as a working medium for artists. The magazine caught the attention of conceptually oriented artists, who formed a rapidly expanding group at the time. This attraction was due partly to the magazine serving as an unconventional medium in which ideas could be conveyed and produced; it was a pre-existing and recognized object, part of the everyday world – systems that artists synonymous with the birth of conceptual art were keen to pursue – and its distribution gave artists a wide-ranging audience on a global scale. Some examples of the bulletin out of the 156 that were produced are Daniel Buren’s entirely transparent issue; Sol Le Witt’s, which broke the standard format of four A4 pages by folding them down into forty-eight rectangles; and one that provided a home for Robert Barry’s Closed Gallery piece. As a whole, the magazine ultimately contributed to altering the understanding of what art could or might be and broke new ground for the making of art.

In the case of Defile, however, when we look a little closer, it becomes apparent not only that advertising space comprises the magazine’s entirety, but that in fact advertising – or, perhaps more correctly, the idea of adverti- sing – is its principle subject and main focus.

While the magazine as work of art provides a backdrop for Terada’s Defile, more pronounced, however, is the system set up by the artist to use the magazine as a device to operate in and with. Defile’s inherent exchange with and trade-off between two subjects is something of a recurring theme in his work – in actuality, a working and guiding principle for his work. This orchestration and choreographing of a pre-existing situation – or, more precisely, the transposition of its elements by retaining its defining parameters and working within them – can be traced back to the work of artists such as Michael Asher, Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren, Dan Graham, Louise Lawler, and, more recently, Maria Eichhorn. For Asher – whose practice involved the removal and, at times replacement, of several elements in a gallery, institution, or museum, such as walls, radiators, or the exhibition space itself – his “use of isolated pres- entation elements disclosed the existence of mediation devices as functioning elements in their own right.”1

This has a particular pertinence to Defile and, more pervasively, to Terada’s practice as a whole. In 2002, for his second solo exhibition at Catriona Jeffries – his representing gallery in Vancouver – Terada placed a full-scale road sign, declaring “Entering City of Vancouver” (2002), from the road into the gallery, with this being the only element on display and viewable from the outside of the gallery space at all times of day by the passing public. You Have Left The American Sector (2005), another work involving road signs, exemplifies the same simple act of transposition, this time underpinned by a much broader narrative: the sign was initially intended for the public space of the city of Windsor, Ontario, but was taken down shortly after its erection for political reasons. Other works by Terada employing pre-existing elements have been purposefully hidden in, camouflaged in, and used the apparatus of an exhibition. For example, The Show Will Be Open When the Show Will Be Closed (2006) existed in two versions: the design of the invitation card and the guide for an exhibition of the same name, as did The Idea of North (2007). These works, like Defile, transformed exhibition ephemera into works of art.

In addition to those mentioned above, there is one work by Terada that is perhaps positioned most closely to Defile, simply titled Catalogue (2003), that might assist with demystifying Defile further. Sharing an involved trade-off between subjects, Catalogue was the consequence of a system initiated by the artist that enabled an exchange. The premise was that Terada enabled ten corporate and eighteen private sponsors to use the entire exhibition area of the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver as advertising space. This was the content of Terada’s solo exhibition in its entirety; nothing else was displayed. The crucial element missing from the exhibition, however, was the art object – the catalogue for the exhibition – which was paid for by the twenty-eight companies in return for advertising in the gallery space. Albeit lavishly designed and produced, the catalogue contained all of content typical of any monograph – texts, reproductions of artworks, and so on – but its status was elevated. Catalogue did what is most brilliantly inherent in Defile: it deceptively elevated a common and usually ancillary element to a work of art unto itself, without ever truly abolishing its form.

Interestingly, the story of Defile has recently had another chapter. Terada has opened out its hermetic-seeming structure to the public, allowing individuals to participate, by producing the work Have You Seen This Kitten? (2008). Functioning as an extension of Defile, the work consists of a printed poster that bears the image on Defile’s front cover, a kitten, and makes a request to the public to locate the twenty- one issues of the magazines that participated in Defile’s exchange program, that were its content and made the magazine possible. Those who complete this task are asked to photograph all of the issues arranged in a stack and mail the resulting photo to Terada’s representing gallery in Vancouver. The poster explains that Terada will sign the photograph, thus authenticating the collected magazines as an artwork. Defile has suddenly gone from a game or story that is completed to one that is in progress – and, vitally, one that is at your command.

Focusing on the rhetoric of signs used in the art-institution system, Ron Terada has been producing conceptual works that question their parameters, diverting the function of exhibition catalogues, signage, brochures, and posters, since the 1990s. His next exhibition will take place in 2010 at Icon Gallery, Birmingham, United Kingdom. Terada was born in 1969 in Vancouver, and still works and lives there. He is represented by Catriona Jeffries in Vancouver.

Adam Carr is an independent curator and writer currently based in London.