[Spring 2010]

The Rise of Abstraction in Photography

Galerie Pangée, Montreal

September 15 to October 12, 2009

Culled from a much larger exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York, curated by Lyle Rexer, author of, among others, How to Look at Outsider Art,1 The Edge of Vision is a very special show that touches on aspects of photography, and what it can do, that other shows would never attempt. Indeed, the accompanying book published by Aperture2 provides insights and background on many photographers less well known to gallery visitors in general.

What distinguishes most of the photographers on view at Galerie Pangée is their innovative techniques and the ways that they bring abstraction into the dialogue on the photographic image and art. One could even go so far as to say that this is a photographer’s show, one in which special techniques and effects, as much as the actual visual image, play a role in the vernacular of art. The best known is Silvio Wolf, who represented Italy at the Venice Biennale. His photograph is a double-entendre, and a double image: one side is light and tactile, all about surface, while the other half is dark, showing a zoom to the surface of human skin – not recognizable as such. The photograph gives a classical atmosphere of balance, even if the images coupled in it are not actually equal in size. The visual ensemble is allegorical, a narrative on photography itself and its medium – light.

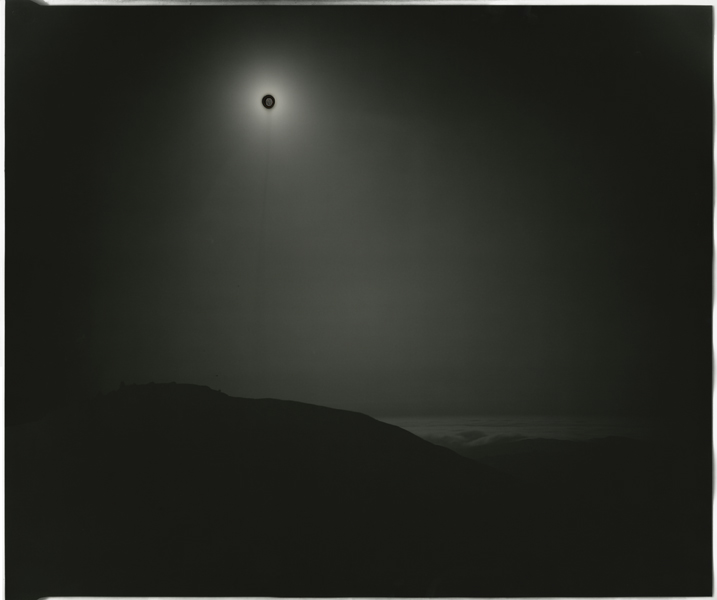

The sun brings the image to Chris McCaw’s paper negatives of desert scenes, made with a homemade 16″ x 20″ camera and a 20″ x 24″ camera built on a garden wagon. McCaw’s pictures capture some sun but are also perforated by exposure to it, and so what happens to these images becomes analogous to what is happening to the global climate as a result of various effects (including ozone depletion). What happens outside the camera is what makes the image, and more directly than a camera with a lens might do. In contrast to the digital photographs of our era, McCaw’s works are acted on by the physical, by solar effects, and thus are linked to more universal, cosmic forces. This is what makes McCaw’s process so intriguing. When his photographic-paper negatives catch a sunburn, they have the look of antiquity; yet, they are contemporary landscape images, with the occasional line that burns through the entire image, similar to Lucio Fontana’s canvases in the 1960s. This time, nature enacts the act of art, with the artist’s assistance, and, chance-like, the art comes into being. In these images, we see a desert scene that evokes the early days of photography, with vague silhouettes and landscape outlines, but a line physically burned into the image by the sun makes this more than a mere photographic image. It becomes multimedia, with nature, in the persona of the sun, playing the active role – and this is what makes the pieces more image objects than photographs.

Michael Flomen’s new series of small camera-less photograms deal with Genesis, the first life on earth. The physics enacted on photographic paper was done underwater. The one large individual mono-print piece involved snow, and, like a Chamberlain sculpture, the photographic paper was crumpled before a second exposure, causing a series of abstract and very alliterative, or allegorical, effects that anthropomorphize the overall image. Is Flomen making a comment on the sophisticated nature of primitivism in art? His pieces are incredibly imaginative and abstract, despite their on-site camera-less capture process. Like a backwoods Brassaï, he works at night in the forests and streams of Vermont producing works that celebrate the magic and mystery of nature and the cosmos.

Ellen Carey’s 20″ x 24″ Polaroids are “pulled” through the rollers of a large-format Polaroid camera so that the chemicals within explode. Intended to cause the development of an image, in this case they come off as entirely abstract flares. Pull with Flare (2008) has a cosmological feel, though the image is achieved through pure chemistry and chance.

Edward Mapplethorpe learned photography working in the darkroom of his brother Robert, but for his abstract photographic images he uses camera-less and conventional techniques in combination. Untitled No. 998 is a one-off chromogenic print. Using microphotography, the action of spinning, and time exposure, Mapplethorpe makes a complex interweave of horsehair the source of the image. He applies a ghost image of the subject to a negative and then turns or spins the photographic paper to generate a circular motif form. As abstraction, the image is elegiac and simply beautiful in its patterning, and this is what makes the image so remarkable as a contemporary photograph.

James Welling’s editioned silver gelatine print Agony (1981) is a beautiful abstract motif, a negative photogram image of a plum blossom, printed in various colour combinations using filter systems. More complex than still lifes and photograms seen in the past, the work is “beautiful” in a modernist sense but uses advanced photography techniques to achieve its results.

Charles Lindsay’s CARBON (untitled) is inspired by the nineteenth-century technique of cliché-verre, an art that involves drawing on glass plates. Experimenting with the physical effects that result from placing carbon-based emulsions, Lindsay, a photojournalist by profession, produces a non-photographic “negative” that can be produced on a large scale. The subject for the image at Galerie Pangée is time-worn plastic; entropy has worked the original plastic form (as it did sculptor Tony Cragg’s early wall-placed pieces) but so does Lindsay, using electricity to stress the material further. The result is an image in altered state.

While Lyle Rexer’s show presents an educated and conscious sense of the history of photography, the accompanying publication opens up the incredible range of techniques and approaches to abstraction in which today’s photographers engage. Viewers less well versed in photography may, however, find the visuals less astonishing than would veteran photographers, who would understand the complexity of process and technique involved in these photographers’ works. This is not concrete photography, as all the optical effects rely on the world in which we live. Despite all the technical gymnastics, The Edge of Vision – The Rise of Abstraction in Photography is a great show that presents a welcome opportunity for Montrealers to experience contemporary photography with an abstract and engaging process-oriented edge.

1 Lyle Rexer, How to Look at Outsider Art (New York: H. N. Abrams, 2005).

2 Lyle Rexer, The Edge of Vision : The rise of Abstraction in Photography, (New York:, Aperture, 2009, 291 p).

John K. Grande is Curator Emeritus of Earth Art at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario. He is the author of Balance: Art and Nature (Black Rose Books, 1994), Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (State University of New York Press, 2007), and Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Pari Publishing, Italy, 2008). His latest books are The Landscape Changes (Propect/Gaspereau Press, 2009) and Art Allsorts: Writing on Art & Artists, 2 vols. (Go If Press, 2008, 2009).