[Fall 2010]

par Mario Côté

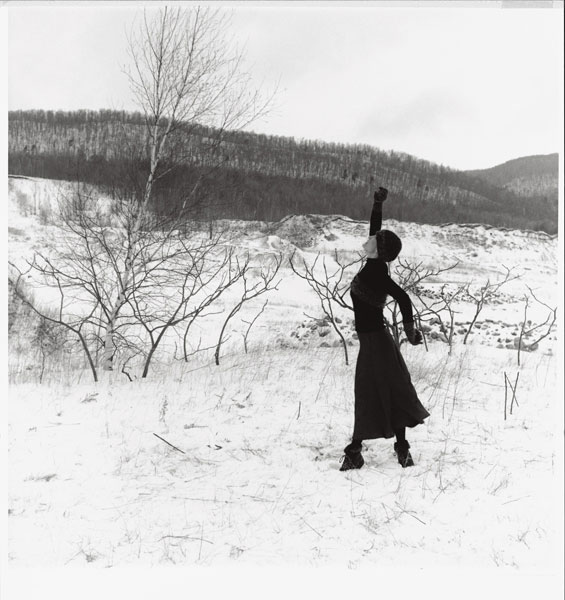

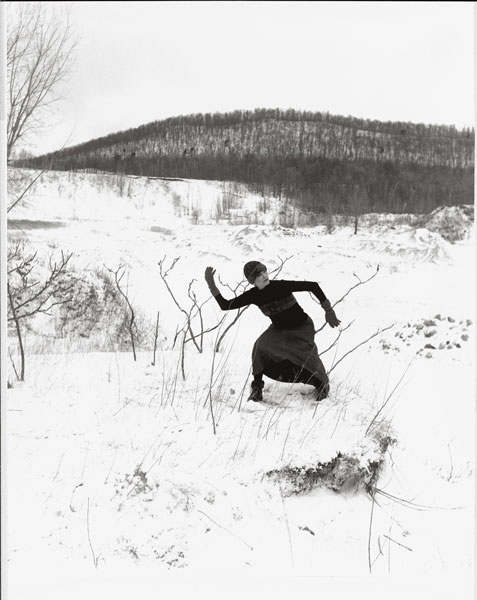

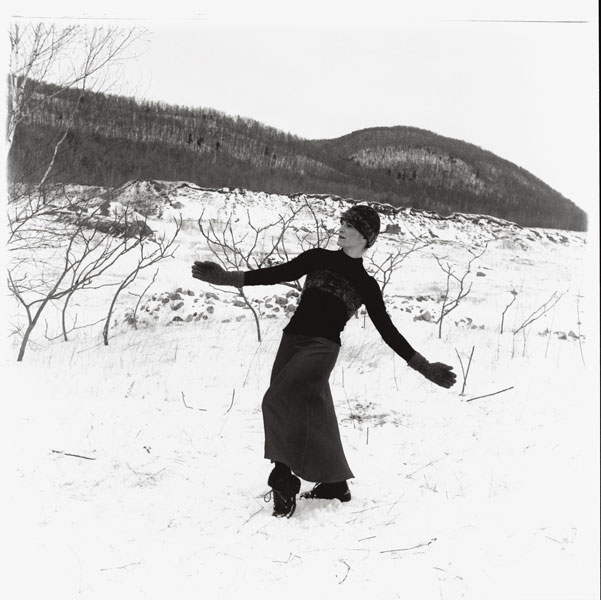

In October 2005, my chance meeting with the multidisciplinary artist Françoise Sullivan at the café of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels led to the idea of reviving, almost sixty years later, an early masterpiece of modern dance: Danse dans la neige. During this encounter, Sullivan explained that the project was part of a larger endeavour of “dances to the rhythm of the seasons.” She told me that in June 1947, upon her return from New York and while on vacation in Les Escoumins, she sketched out the first steps of a choreography, which was filmed by her mother with a 16 mm camera, on the rose granite rocks beside the St. Lawrence River.1 Then, she told me about the context for creation of Danse dans la neige, an event that took place on 28 February 1948. This time, Jean-Paul Riopelle was operating the film camera and Maurice Perron joined them to take the famous photographs that later became the only visual record of the event. Unfortunately, the reels of film shot in the summer of 1947 and the winter of 1948 have been lost.2 On the other hand, Perron’s photographic documentation remains to provide a valuable record of one section of the cycle of the seasons, that of an early performance of a dance “in” the snow – in the sense of “playing in the snow.”3

Documentation of live shows and performances has always given rise to misunderstandings and legitimate copyright claims. Of Sullivan’s remarkable choreography, there remain only some twenty photographs taken by Maurice Perron, which have become the sole trace of this extraordinary, historic moment. In 1977, Sullivan self-published a limited-edition picture book (53 copies) containing seventeen photographs by Perron. Later, in 1998, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, in the exhibition “Mémoire objective, mémoire collective. Photographies de Maurice Perron,” presented a series of twenty photographs of Danse dans la neige – thus, three more than in the book – in a completely different order. The two artists thus found themselves “signing” a single work of which they had very different views: the choreographer considered the documentation to be secondary to the work; the documentary photographer considered his images to be a work in their own right. The creator of the choreography for Danse dans la neige and the status of the photographic documentation of this work were the centre of an exemplary debate. It was in this controversial context that the project to re-create Danse dans la neige was born.

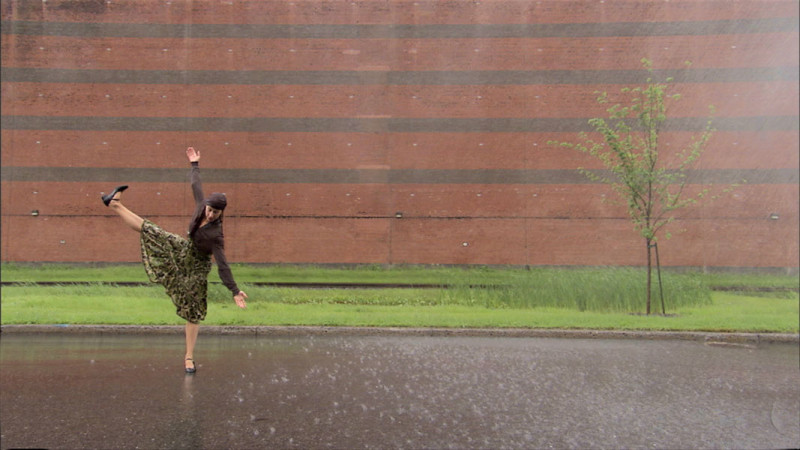

It must be specified immediately that re-creating and filming Danse dans la neige fell within the context of a larger project of portraying the four seasons of the year, which corresponded more to Sullivan’s initial idea. We co-produced the document in high-definition digital Beta with the title Les Saisons Sullivan, which was complemented by a new book of photographs, edited by Louise Déry and published by Éditions de la Galerie de l’UQAM with a print run of one hundred copies, depicting the process of the re-creation. Also titled Les Saisons Sullivan, it includes sixty-seven photographs taken by the artist Marion Landry during shooting and four drawings by Sullivan. A filmed work and photographic documentation thus form the two parts of the project of re-creation and reinterpretation of Les Saisons Sullivan.

It went without saying that we would start with Danse dans la neige. On 10 February 2006, at an important meeting with a skeleton production team, composed of dancer Ginette Boutin, director of photography Steeve Desrosiers, Françoise Sullivan, and me, we decided on the aesthetic point of view, the choice of movements to be danced, and a shooting script. To our surprise, a close examination of the suite of photographs that Sullivan had published in the 1977 book led us to reconsider both the shooting script and the choreographic sequences. Today, we can easily subdivide the original photographic corpus into four separate groups of pictures, according to the point of view adopted by the photographer at the time, Maurice Perron.

The danced performance was executed in a single location: a snowy clearing near the municipality of Otterburn Park, close to Mont Saint-Hilaire. The first group of photographs (1 to 44) shows the dancer moving on a small hill situated on the north side. We clearly see a first horizontal line indicating that there is a change in ground level behind this first plane. Then, farther away, a second raised parallel line, bordered by a few trees and a fence, gives a glimpse of a second elevation. A ravine separates them. The depression in the terrain is particularly visible in the first picture, for which the photographer is slightly turned westward, and reveals in the distance, with a greater depth of field, a stream in the centre and a tree on the left. A second group of two photographs (5 and 6) offers a moment of passage, a transition, since the photographer has descended the snowy plateau and adopted a low-angle point of view, more dynamic and oriented eastward. We see the dancer, ready to move energetically to hurtle down the snowy slope. An important detail draws our attention: we can glimpse, in the background of photographs 3 and 5, part of Mont Saint-Hilaire. The third group (7 to 14) shows the main part of the choreography: the dancer performs on the southern slope of the hill, which seems steep and uneven in places. The horizon line is situated in the top quarter of the image. The landscape is particularly desert-like, with no trace of life. A number of commentators have talked about the lunar aspect of these photographs, since the snow on the ground is hard, even icy. Finally, in the fourth group of photographs (15 to 17) the photographer, while at the same spot, has changed the camera axis to point westward. The composition is more dynamic, since the hill on the horizon is now at an oblique angle. The last two photographs show the dancer near a tree at the right that reinforces the framing. We can easily deduce this since the tree is the same one as in the first photograph. Other clues – the glancing light, the elongated shadows – indicate that the pictures were taken in the afternoon. In short, the first and last pictures serve as introduction and conclusion by re-establishing the dancer in a realistic landscape, while the middle part takes place in a strange, enigmatic setting in which the movements take their impetus from this encounter with the elements of nature.

We must return to the first group of four photographs, which were the main subject of our discussions, and which respect the order suggested by Sullivan. And yet, this group poses a difficulty with regard to the movements actually made by the photographer in the short span of time available to him to take his pictures. Photograph 1, like the opening shot of a film, gives a panoramic overview of the scenes to come. It is coherent. On the other hand, the sequencing of the three following photographs is problematic. Photograph 2 shows the dancer facing the camera, and photograph 3 indicates a change of axis: the photographer therefore had to move far to the left to bring his gaze to the eastward direction. Then, in photograph 4, he returns to the starting position facing the dancer. How, in such a short time, was it possible to move to take photographs 2, 3, and 4? And yet, if we look closely at photograph 3, it could easily fall within the narrative continuity established by photograph 5: a close shot of the dancer, then a shot taken from a distance as the photographer moves away from his subject. In addition, a look at shots 3 and 5 in succession reveals a single point of view of Mont Saint-Hilaire from different distances. Why did Sullivan place a more dynamic shot between two more static ones? Was this a formal choice or a decision that corresponded to the choreography at the time? This sequence of shots would have consequences for both the filming and the reconstruction of choreographed movements. It is very interesting to observe how different criteria were used in the ordering of these famous pictures. Perron had made a free variation from the choreography, since he was above all a well-known documentarian of the Automatist movement. Sullivan, more respectful of the order of the choreography, nevertheless introduced some formal liberties. And, finally, the Les Saisons Sullivan project, in trying to be objective, attempted to respect the photographer’s and cameraman’s points of view, since the two were working side by side, as Sullivan described a number of times.5 In the end, did the process of analyzing the photographs lead to a true reconstruction or to a free reinterpretation?

Shooting was done over two days, 3 March and 5 March, 2006, in the Maska quarry at Mont-Saint-Hilaire. Two sites were chosen: one on top of a small hill that was covered with snow during the week preceding shooting; the other, below, with a view of a very snowy secondary road. The shooting script tried to respect the choreography as it had originally been produced. Sullivan worked from memory, assisted by photographs, to re-create the choreography in her studio. Ginette Boutin’s costume was also designed from the original photographs and the description given by Sullivan. It was a cold day, –7° C with a 60 km/h wind, and powdery snow replaced the icy crust of the original. One might say that the new document revived a dance sequence that had been “frozen” on film. We started from a photographic document intending to be as faithful to it as possible, but new avenues led us to produce an original creation based on those premises. As proof, the four first photographs of the 1948 performance, those brought together in the 1977 picture book, and those taken from the videographic document are very different. In this context, one would more easily talk of “remediatization,” since the basic material, a sequence of black-and-white photographs, led to blue-saturated videographic images. The idea was to evoke old black-and-white movies broadcast on colour television sets, causing them to be tinted blue. The 1948 photographic sequence had no sound, while the 2007 document has a sound track composed of ambient noises recorded during shooting, but also an accumulation of a number of winter audio strata recorded at various places, including the winds of Mont Sainte-Victoire! Finally, the image editing brought to light a group of movements danced in the intervals between photographs. It is thus more correct to speak of re-creation and reinterpretation than of reconstruction of Danse dans la neige, made with the cooperation of the artist and with her complete agreement, since she attended to all steps of the new production, giving her point of view throughout.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 For more details on the circumstances surrounding the origin of the project, see the introduction by Louise Déry in Les Saisons Sullivan (Éd. Galerie de l’UQAM, 2010, facsimile); Gilles Lapointe, La Comète automatiste (Éd. Fides, 2008); François-Marc Gagnon, Chronique du mouvement automatiste québécois 1941-1954 (Montreal: Lanctôt éditeur, 1998); Claude Gosselin, Françoise Sullivan. Rétrospective (Quebec City: Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1981), catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain, Montreal, from 19 November 1981 to 3 January 1982.

2 In a long footnote in his La Comète automatiste (p. 145, our translation), Lapointe confirms that the film was lost by the filmmaker Guy Borremans: “Around 1957, Sullivan lent him two 8-millimetre films for viewing; Guy Boremans later explained that these films were lost at the same time as a number of his photographs and a film produced with Luce Guilbault” (e-mail from Guy Borremans to Rose Marie Arbour, 10 October 2007). [Editor’s note : it should be mentioned here – without going into further detail – that the rights holders to Maurice Perron’s estate contest this version of the facts.]

3 The historian Ray Ellenwood confirms the extraordinary nature of this work: “These ‘performances’ outside the normal theater context were apparently the first of their kind in Québec and certainly some of the very earliest in Europe and America.” Ray Ellenwood, Égrégore. The Montréal Automatist Movement (Toronto: Exile Editions, 1992, p. 127). See the important chapter “Le Nord vu de la chambre automatiste: l’expérience de Danse dans la neige” in Lapointe, La Comète automatiste, pp. 137–56, in which the author develops the thesis of the originality of the performance in North America or, at least, in Northern countries, in that period.

4 I will comment on these first four images in detail below.

5 Louise Déry, Les Saisons Sullivan, p. 163.

Editor’s note: Every effort was made to include Maurice Perron’s original photographs in this article, but the family refused to let them be published in this essay.

One of the signers of the Refus global manifesto, Françoise Sullivan first made her mark in the dance world before exploring abstract sculpture, drawing, photography, installation, and painting, media that, in turn, pro- vided new impetus to her career. She received the Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas for her body of work in 1987, and was awarded an honorary doctorate from Université du Québec à Montréal and York University and made a member of the Order of Canada in 2001. Sullivan is represented by Galerie Simon Blais in Montreal and Galerie Jean-Claude Bergeron in Ottawa.

Mario Côté is a multidisciplinary artist and a professor at the School of Visual and Media Arts at Université du Québec à Montréal. He has produced some twenty video works that address issues of the dancer-body and the reader-body. He has published with research groups, written a number of articles on artists, and contributes a column on video to the movie magazine 24 Images.