[Spring/Summer 2011]

John Baldessari

Pure Beauty

Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York

October 20, 2010 to January 9, 2011

Conceptual art ideas are pervasive in John Baldessari’s art, from his videos, to his photographs, to his hybrid photo-painted works. Presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Tate Modern in London, and following on from the Hirshhorn Museum’s “2007 Ways of Seeing” show, “Pure Beauty” puts another feather in John Baldessari’s cap as a West Coast progenitor of all that conceptual art was, is, or can be. His blending of photography, performance, video, and painting treads the edgy border between visual and textual with a natural affinity. Seen cumulatively, these 120 works, dating from 1962 to 2010, use image as text, and vice versa, with a witty vernacular feel for the moment. The photograph, as a “faux document” that is true to art, builds and plays with visuality throughout Baldessari’s oeuvre as it narrates its way from real to art and back again. Indeed, to experience his lifelong repertoire of art is to see significant differences between the West Coast and New York contemporary art aesthetics. With Baldessari, we are witness to something close to concrete poetry. Is he thumbing his nose at highbrow conceptual art’s Duchampian origins or affirming them? Certainly, he has hybridized it, as it was possible to do on the margins of an emerging art empire in the 1960s and 1970s, in the rich California culture that gave rise to Easy Rider, Jim Morrison, and the Grateful Dead.

As legend has it, in 1970 Baldessari began to suspect that there was more to art than painting, so he destroyed most of his art dating from 1953 to 1966 for the Cremation project (1970). A few pieces survived, notably Tips For Artists Who Want To Sell and Clement Greenberg (1966–68), and the box of art ashes from the Cremation project was included in “Pure Beauty.” As David Salle, a student of Baldessari’s at the California Institute of the Arts in the 1970s, comments in his catalogue essay, “What the aesthetic of John’s work accomplished was to give the everyday-Joe artist a way to embrace and lavish a little love on the everyday-Joe visual culture that is all around us all the time, especially if one is stuck in the provinces and really doesn’t have access to the ethos or the rationale of a more highbrow style.”1

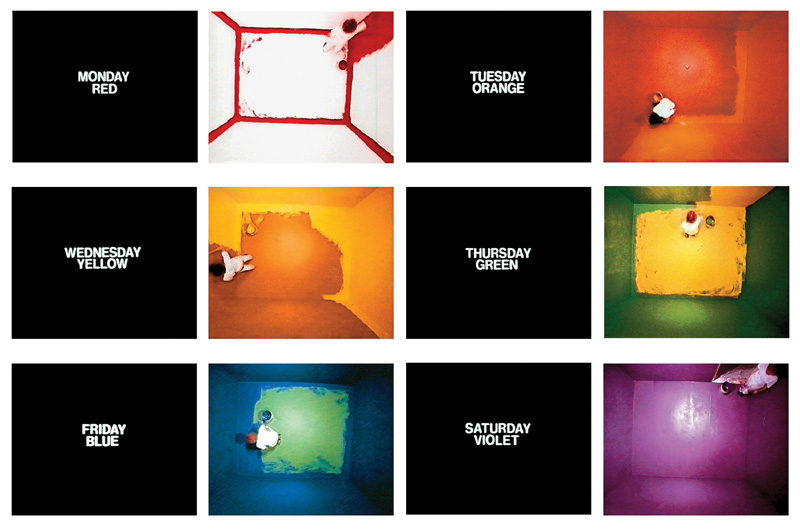

One of the best pieces in the show is Six Colorful Inside Jobs, a video work of a student painting a minute room, as seen from above, each day in a different colour – first red, then orange, and so on, until the six colours of the spectrum wheel are completed. Paint rollers moving, the sweep and method of these actions, like acting performed without a hint of art, and always shown from the same angle – it is all the more art-like as non-art that is art. Also in the show are Baldessari’s brightest, most engaging photoworks, such as Aligning Balls (1972), in which he captures a red-coloured ball in thirty snapshot images. The sky, treetops, and any variety of small details appear, but choice is essential: time is a factor in taking the picture, for the ball is in the air for only a few moments. The photograph becomes a stage, re-enacting its recurring red-ball motif in a no-mans-land. The same stagey sense is in Floating: Color, in which, from the second floor of his house in Santa Monica, Baldessari displayed and photographed sheets of variously coloured paper, altering the scene to be captured in a way that was uniquely his own, almost pantomime, exploiting photography’s potential with a biographical accent. Baldessari has his own nomenclature, just as Ed Ruscha’s has his. Both speak a Californian dialect that is universally open, accessible, and as dry as semi-desert air. Indeed, Baldessari’s 1963 work The Backs of All the Trucks Passed While Driving From Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday, January 20, 1963, with its serial grid-like presentation, actually predates Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966).

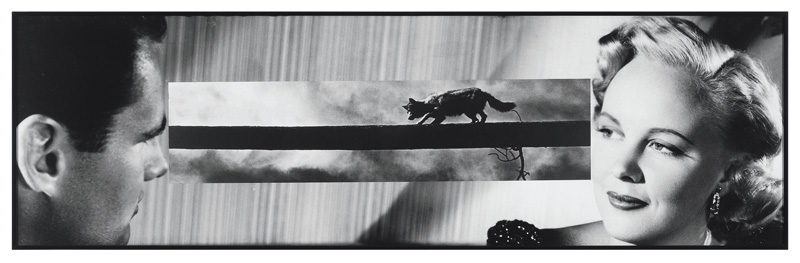

And the Hollywood movie background was there; people sensed it, drew on it, even if it was never in their mind. John Baldessari’s art is sublime and photographic even when the visuality of painterly collaboration enters the viewfinder. As he mapped out visual concepts, Baldessari pioneered new ways of projecting a visual interpretive language that, though whimsical, is always accessible. His narrow band of conceptual art continues to inform contemporary photography, precisely because it uses an informed “language” to lean on, but, as “Pure Beauty” evidences, the fun-loving conceptual art of Baldessari’s era was naïve and open to chance. After all, wasn’t it Baldessari who claimed, “The worst thing ever to happen to photography was the viewfinder”?

With Baldessari now close to eighty years old, his art has a new lease on life because of the way that conceptual art seems to endlessly reinvent itself through the art schools, on its way to the art market. And when Baldessari captures a moment, it is a serial event, locating itself somewhere between performance art and photo document. His work was far in advance of Jeff Wall, or Rodney Graham, or, more significantly, Iain Baxter and N.E. Thing Co. Baldessari exploited that dry, overly conceptual bias like a master. His photography reifies the inbuilt insecurity that West Coast artists felt, regarding the origins of avant-gardism and the prima terra of contemporary art. But how subtle and ingenious is Baldessari’s sense of how contexts can shift and, hence, of how art can acquire new meanings, and of how life invades art. Bringing its enigmatic, mercurial essence into the equation is exactly what Baldessari’s witty, ironic, iconic aesthetic stance was and is about – very West Coast.

John K. Grande is author of Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (State University of New York Press, 2007) and Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Italy: Pari Publishing, 2008). Recent books include Natura Humana: Bob Verschueren’s Installations (Editions Mardaga, 2010) and Homage to Jean-Paul Riopelle (Prospect/Gaspereau Press, 2010). www.grandescritique.com