[Spring/Summer 2011]

by Pierre Dessureault

Pierre Gaudard is one of the rare photographers whose photographs are not on the Web. Absent from the photography scene since the mid-1980s because he returned to France and because of the gradual disappearance of the documentary genre from institutions devoted to photography, his name was suddenly resurrected in a press release announcing his death on 22 July 2010. Gaudard was born in Marvelise, France, in 1927; he studied the art and craft of making books at the École Estienne in Paris, and then moved to Montreal in 1952. After holding various jobs, including lab technician at the National Film Board of Canada, he became an independent photographer in the early 1960s, fulfilling commissions for many magazines, various federal and provincial departments, and the Quebec tourism bureau.

Like many of his contemporaries, Gaudard had a close relationship with the NFB’s Still Photography Division. In the wake of John Grierson’s creation of the documentary tradition that prevailed at the NFB at the time, the organization was attempting to redefine its mission as a governmental information agency in order to present photography not only as a means of examining social issues but as a medium on its own and not a poor relative of the fine arts.

Pierre Gaudard is one of the rare photographers whose photographs are not on the Web. Absent from the photography scene since the mid-1980s because he returned to France and because of the gradual disappearance of the documentary genre from institutions devoted to photography, his name was suddenly resurrected in a press release announcing his death on 22 July 2010. Gaudard was born in Marvelise, France, in 1927; he studied the art and craft of making books at the École Estienne in Paris, and then moved to Montreal in 1952. After holding various jobs, including lab technician at the National Film Board of Canada, he became an independent photographer in the early 1960s, fulfilling commissions for many magazines, various federal and provincial departments, and the Quebec tourism bureau.

During the 1970s, Gaudard played a leadership role in the diversification of documentary approaches that dominated much photographic production in Quebec at the time.

Like many of his contemporaries, Gaudard had a close relationship with the nfb’s Still Photography Division. In the wake of John Grierson’s creation of the documentary tradition that prevailed at the nfb at the time, the organization was attempting to redefine its mission as a governmental information agency in order to present photography not only as a means of examining social issues but as a medium on its own and not a poor relative of the fine arts. This intention was conveyed in practice by giving photographers great latitude in the choice and treatment of the subjects commissioned from them and by emphasizing their personal vision, which became as important as the information conveyed by their images. Among the many photo essays produced by Gaudard during this fertile period, those depicting the Jewish community of Montreal and the federal electoral campaign (1963), the Montreal elections (1966), and youth and counterculture (1968) displayed a sense of observation and empathy that was fully expressed in his major personal projects of the following decade.

In parallel with its information-related activities, the Division instituted a major program of exhibitions and publications designed to promote the best of Canadian photographic production. Gaudard’s photographs figured in a number of the publications, and his record of his five months of travel through Mexico and Guatemala in the winter of 1956–57 was featured in one of the first exhibitions produced and presented by the Division in its Ottawa space in 1963.

During the 1970s, Gaudard played a leadership role in the diversification of documentary approaches that dominated much photographic production in Quebec at the time. He and a number of other photographers produced sweeping projects representing milestones in the development of a vision of Quebec in the midst of seeking its identity. Some, such as Gabor Szilasi, studied Quebec’s transition from rural to urban; others, such as gap (Groupe d’action photographique) and gpp (Groupe des photographes populaires), used the medium as a consciousness-raising tool; still others, such as Michel Saint-Jean, followed the movements in the social landscape; and finally, photographers such as Clara Gutsche and David Miller promoted preservation of an urban patrimony.

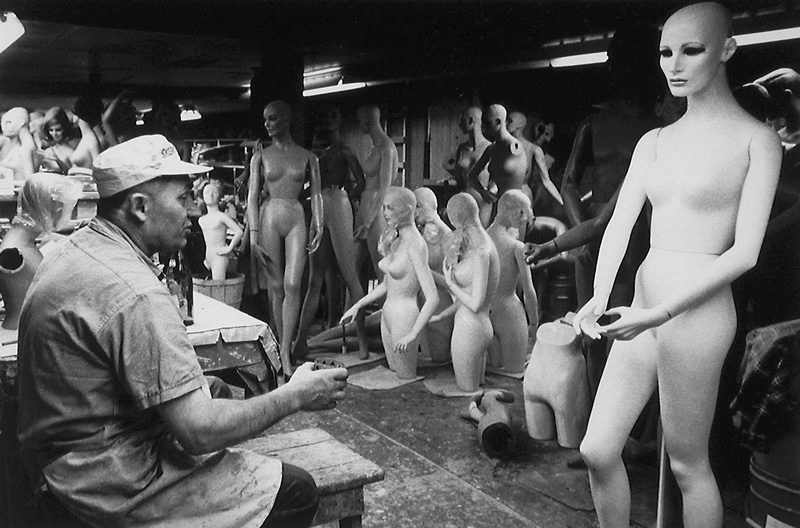

The three sets of works that Gaudard produced at the time were unique for their depth of view and their engagement in social reality. His first major personal project, Les Ouvriers,1 like its exact contemporary, Szilasi’s series on Charlevoix and l’Isle-aux-Coudres,2 marked a break with photojournalistic approaches related to current events in favour of documentary discoveries. For two years (1969–71), Gaudard travelled through various regions of Quebec, encountering people in their workplaces and homes in order to paint a portrait of the life of factory workers. His curiosity about this milieu and his desire to understand it served as his guideline: “I absolutely do not want to prove anything. If my photographs have a message, it is not deliberate on my part; my goal is not to defend a cause through photography. Rather, I would say that I am witnessing my times; I want only to present to as many people as possible a portrait of the society in which they and I live.”3

The frontal, neutral approach, the accuracy of the facts observed, and the clarity of the depiction bespoke Gaudard’s descriptive intention. He privileged a snapshot aesthetic, crystallizing a moment by focusing completely on the subject. In his desire to melt into his surroundings and record truth as fully as possible, he used a simple Leica and shot in natural light. This economy of means was in phase with his position as interlocutor addressing a person face-on in an exchange of gazes that states the deliberateness of the encounter between the photographer and his subject. The person thus singled out becomes an individual who, although we know little about him, affirms his presence to himself and to others through the image. The presentation of people in their workplace or their daily environment brings to the forefront the familiarity that comes from situating faces in a context swept by a multitude of signs, objects, and images that signify their belonging to a place and a moment in history. In doing this, Gaudard avoids transforming his subjects into social paradigms and making them into archetypes that would serve as heroic figures for activist propaganda.

In 1975, the Canadian edition of Time commissioned from Gaudard a series of photographs to accompany an article on prisons. In this photojournalistic context, the images illustrated the text, which was the essential vector of information. Les Prisons4 became a documentary project when Gaudard expanded the subject by choosing to spread his work over a one-year period, repeatedly visiting detention centres in Quebec and the prison for women in Kingston.

With their rejection of the spectacular, the sentimental, and the didactic, Gaudard’s images are situated in contrast to the repertoire of stereotypes associated with prisons and the incarceration system.5 Their informative value comes from an inventory of details and an examination of everyday things the accumulation of which ends up painting a portrait, in successive strokes, of the lives of individuals in a particular context: smooth grey cell walls and endless corridors, omnipresent guards, walls scarred with graffiti or adorned with pin-ups and pictures of dear ones, the prisoners’ identical uniforms. From this abundance of details and with a sharp gaze that grasps the fleeting meaningful instant in the flow of daily banality, Gaudard depicts a world in which the power plays among guards, bosses, and prisoners can be seen everywhere and the closed space of the cell reflects the prisoners’ solitude. In these images, the photographer’s intention surpasses simple description to bring to light an iconography of imprisonment; it is the inner prison that dominates. The image of the prisoner standing against the grey wall of his cell, squeezed between a bed, a toilet bowl, and a sink, becomes a metaphor for the internal imprisonment that is read in his face.

In 1979–80, Gaudard travelled for several months around France, the country he had left in 1952. Retours en France6 stands out from his previous projects in both approach and style. As he travelled, Gaudard harvested moments and events that portrayed the amusement and surprise of someone who is reviving and wondering about his ties with his homeland. Avoiding picturesque, emblematic sites and the exoticism of received images of France, the photographer immersed himself in the theatre of the street, sought out ordinary living spaces, and delved into small rituals that mark daily life, to reveal a social landscape saturated with visual dissonances, in which we see the strange cohabitation of two worlds and the invasion of the cultural space by the United States and its symbols.

Gaudard abandoned his reserve and neutrality to take a position; he threw himself to making images more freely, coloured with his personal, often ironic reactions, displaying a point of view nourished by the distance provided by thirty years of living in Quebec. The cultural codes that formed the social fabric had evolved in both places, and the encounter between the photographer and his subjects was constantly renegotiated. While the snapshot was always favoured, the wholesale capture of moments, combined with the act of seeing, the recognition of the situation, and the photographer’s gestural nature, became essential components of the image. In this sense, the photographs in Retours en France belonged to the social landscape and constituted the photographer’s commentary on his original culture.

The visual and thematic continuity of each of Gaudard’s projects had to do as much with the wealth of their content and the strictness of the documentary intention as with the unity of the approach and the coherence of the photographer’s vision. For him, it was a matter not just of visiting the working-class world, shining a light on the world of prisons, or making observations inspired by his return to France, but also of communicating his discoveries in a personal way; though his intentions were clearly displayed, they never took away from his choices. The factual truth was thus constantly relative to the photographer’s truth and the acuity of his comprehension of the social milieu, and the resulting images exist in an array of gazes: the gaze of the photographer at his subjects; the subject’s gaze directed at the photographer; the gaze of contemporaries at the image; and the retrospective gaze that we direct at the same image. “Photographic images themselves are only voiceless memories of our passing gazes. We bring them to life only if they first bring back our own memories. The gazes of two viewers looking at the same photograph diverge when it does not evoke the same memory for each of them. The reminiscing gaze of today’s viewer is different from the long-ago gaze that existed when the photograph was taken and is concretely expressed in it.”7

We therefore witness the ruptures and fractures of the historical distance that has marked the decades since when Gaudard’s images were produced. Stepping back, seeing the image of the world conserved archivally, is to update – with today’s eyes, with our present values – a past that no longer exists except as photographs. We do this to reconstruct the history of what they portray: Quebec society, its values, and the conflicts that stirred it at a decisive moment – in short, the content of the image – but also the gaze that the era focused on itself through the work of the documentary maker and the characteristics of the medium that served as his tool.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Les Ouvriers was presented at the nfb’s Galerie de l’Image in Ottawa in 1971 and at the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal in 1972. A publication with an introduction by Gérald Godin was published by the Photography Department: Image 10 Les Ouvriers (Ottawa: Martlet Press, 1971).

2 See David Harris, Gabor Szilasi – L’éloquence du quotidien (Musée d’art de Joliette and Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, 2009), particularly pp. 16–23 and plates 23–59.

3 Pierre Gaudard, Les Prisons, brochure accompanying the eponymous exhibition (Ottawa: nfb, April 1977), n.p. (our translation).

4 Les Prisons was presented at the nfb’s Galerie de l’Image in 1977. Some of Gaudard’s images were published in the Montreal magazine ovo, no. 24–25 (1976). In this thematic portfolio containing texts by prisoners, social workers, and analysts as well as a group of historical photographs and a directory of prisoners’ assistance organizations, Gaudard’s photographs, although they comprised the lion’s share of the visuals, were in a way simply evidence designed to buttress the point of view expressed in the editorial in the issue: “We have the right to ask the question: When will prisons be abolished? And in all of its forms, even mitigated: prisons without bars, internment in camps, monitored freedom. . . . And if we indefinitely leave this responsibility to our solicitors general and our ministers of justice, is it by ignorance or complicity?” (p. 3, our translation). About the photographer, there was only a short biography; about his project, a short descriptive note on each institution. There was no mention of his intentions or his work.

5 One of the few documents dealing with the same subject at the time is Danny Lyon, Conversations with the Dead (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971). In his book, Lyon presents a series of images gathered during his eighteen months of visits to penitentiaries in Texas, reputed to be the toughest in the United States, accompanied by files on prisoners and correspondence with one of them, Billy McCune, in which McCune tells his personal story and how he came to be in prison. As a whole, the book is a powerful indictment of an obviously inhumane system.

6 Retours en France, renamed En France, was the subject of an exhibition at the nfb’s Galerie de l’Image in 1982.

7 Hans Belting, Pour une anthropologie des images (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), p. 278 (our translation).

Pierre Dessureault is a historian of photography and an independent curator. He has organized numerous exhibitions and published a large number of catalogues on contemporary photography.