[Fall 2011]

by Franck Michel

From 9 February to 10 April 2011, the Maison européenne de la photographie in Paris presented the first-ever retrospective of the works of photographer and writer Hervé Guibert, comprising some 230 images.1 I had a chance to visit the exhibition on a weekday morning when the museum opened, so I was just about alone in the galleries (something rare at this museum). This is worth mentioning, because the imposing number of small-format black-and-white prints and their tight presentation in two rows required a patient and attentive viewing, which is certainly very difficult when there are crowds of people. Finding myself alone before these emotionally charged photographs, I had time for some contemplation.

Yet, his images have a remarkable visual sensitivity and an undeniable photographic quality, as revealed in his mastery of technique, framing, and light.

The images chosen for the exhibition were based on the selection made by Guibert, not long before his death, to form his photographic legacy. Guibert was a great writer and an icon of the “AIDS years.” Many of his books were bestsellers that made a mark on an entire generation. In 1981, he published L’Image fantôme – one year after Barthes’s La Chambre claire came out and exploring many of the themes – a subjective reflection composed of short essays on his ambiguous relationship with photography. For people who, like me, studied photography in the 1980s, L’Image fantôme was considered as much a cult book as La Chambre claire. From 1977 to 1985, Guibert was also a photography critic for Le Monde.

When Guibert was around twenty years old, his father gave him a small camera, a Rollei 35, which he continued to use until he died, much too young, at age thirty-five, in 1991. Although he did not consider himself a photographer, his photography always played a central role in his life and cohabited with his writing, each nourishing the other. “I will always deny being a photographer,” he wrote. “This attraction scares me; it seems that it may quickly turn to madness, for everything is photographable, everything is interesting to photograph. And how can one divide a day in one’s life into thousands of instants, thousands of tiny surfaces – and if one starts, why stop?” 2 Yet, his images have a remarkable visual sensitivity and an undeniable photographic quality, as revealed in his mastery of technique, framing, and light. This is far from amateur photography.

As an intellectual and artist of the 1980s, Guibert was part of the movement that Gilles Mora and Claude Nori have called “photobiography.”3 Appropriating the break with the past produced by Robert Frank’s work, a number of young photographers of the time – when photography in France was undergoing a dazzling rise in popularity4 – created a form of photography that was anti-spectacular and anti-sensationalist, that focused on the daily and the banal, even the chance and the unconscious, rather than events. “Photography became the experience of the invisibility of the world,” as Jean-Claude Lemagny put it so succinctly (our translation).

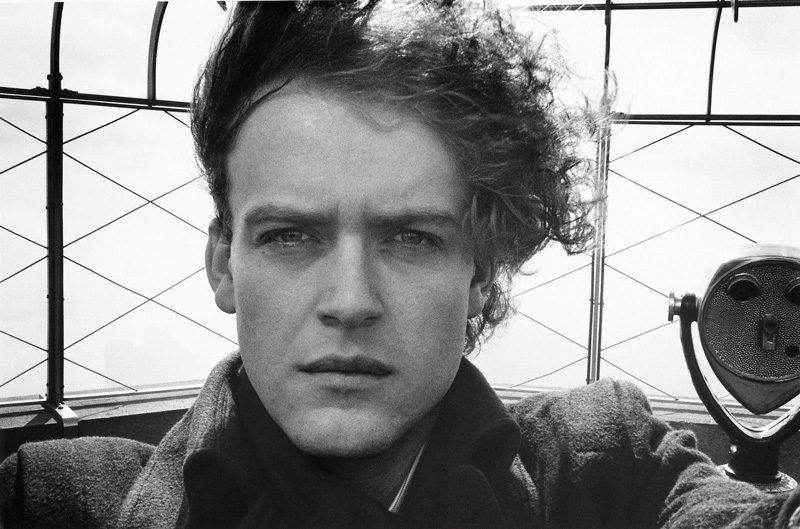

Guibert’s photographs are, above all, fragments of life wavering between reality and fiction. Interested in the private world around him, he photographed lovers, friends – among whom we recognize some of the famous names of the 1980s, including Foucault, Adjani, and Tarkovski – objects dear to him, and places that he visited or lived in: hotel rooms, apartments, artist’s residences (a number of photographs resulted from a residency at the Villa Medici). His images, with their contrasting black and white and clean compositions, speak to us of encounters, break-ups, the fragility of existence, and, above all, desire – a deep, intense desire often flirting with eroticism.5 He was also fascinated with the morbid: hanging puppets, relics, inert living bodies. From the first images in the exhibition, devoted to the wax mannequins of the Musée Grévin, to the self-portraits showing the deterioration of his own body ravaged by aids, this fascination appears as a leitmotiv throughout his work.

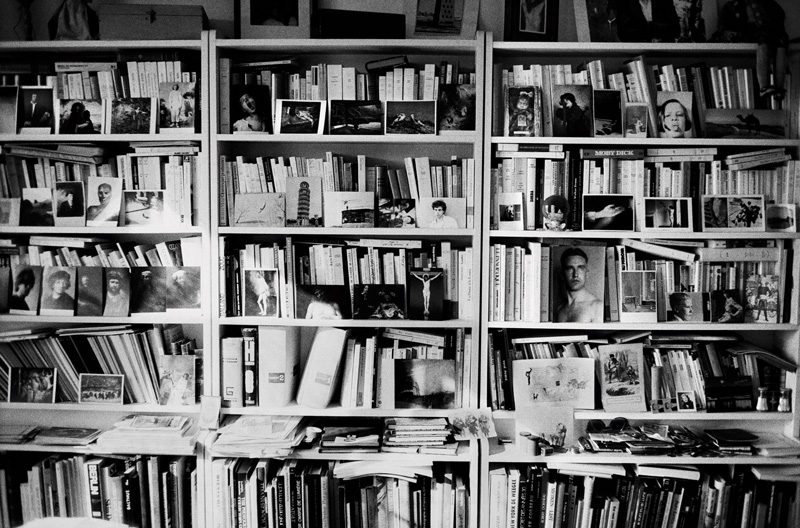

In his novels – most of them autobiographical in nature – as in his photographs, Guibert shows an obvious narcissism, which is conveyed in many of the self-portraits. He liked to project a romantic image of the writer – handsome, a bit bohemian, and timeless. Other carefully composed shots show his worktable sprinkled with handwritten pages, postcards, and small reproductions of works of art, accompanied by his Mont Blanc pen and his old typewriter. Through these images, he constructed and maintained his own myth as a writer.

This exhibition, magnificent despite its space problems, profoundly moved me. However, I wondered, as I left the museum, what people who had not lived through the aids years and do not know Hervé Guibert the writer would take away from the exhibition. Of course, there will always be this essential testimony to an era that was both beautiful and disrupted. But beyond that, will Guibert be considered a full-fledged photographer or be counted among the many writers who picked up a camera from time to time and to whom a picture book or an exhibition is devoted but whose photographic work may be quickly forgotten? I dare to hope that the former turns out to be true, and I would go so far to deplore the fact that during his lifetime, Guibert’s literary work was so obsessed over and his photographic work so little seen. He was indeed a photographer, and his images, with their overt sensitivity and mysterious beauty, are the most eloquent evidence of this.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Quoted by Amo, Hervé Guilbert, back cover (our translation).

3 Gilles Mora and Claude Nori, L’été dernier, Manifeste

photobiographique (Paris: Édition de l’étoile, Écrits sur l’image coll., 1983) (our translation).

4 Among the best known are Bernard Plossu, Yves Guillot, Arnaud Class, and Raymond Depardon. Jean-Claude Lemagny wrote, on the influence of Robert Frank, “Here was finally a photography that expressed the squalid mediocrity of everyday life because it contained itself within its powerlessness to express anything. It knew to respect the absurdity of facts and the moment before or after the instant chosen for its significance.” L’ombre et le temps, essais sur la photographie comme art (Paris: Nathan, coll. Essais et Recherches, 1992), p. 211 (our translation).

5 He wrote in L’image fantôme, “The image is the essence of desire, and desexualiz-ing the image would be to reduce it to theory.” L’image fantôme (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1981), p. 89 (our translation).

Franck Michel has been working in the visual arts community, particularly in photography, for more than twenty years. He was a researcher and exhibition curator for Mois de la Photo à Montréal, then editor-in-chief of CV Photo and director of Galerie VOX. He curated Gabor Szilasi’s first retrospective (MBAM, 1997), as well as retrospectives of the work of Arnaud Class (1999) and Michel Saulnier (2008). From 1999 to 2008, he was director of Centre Est-Nord-Est, résidence d’artistes et diffusion en art contemporain; since December 2008, he has been director of the Musée régional de Rimouski.