[Fall 2011]

by Alexis Desgagnés

There are still many gaps in our knowledge of the history of Quebec photography. I realized this after seeing “Photographes rebelles à l’époque de la Grande Noirceur (1937-1961),” which was held at Maison Hamel-Bruneau in Quebec City from 9 March to 22 May 2011. Devoted to photography during the Duplessis era, the exhibition comprised about eighty works produced by famous and less-well-known figures from the history of Quebec art and cinema, including Albert Dumouchel, Jauran (Rodolphe de Repentigny), Jean-Paul Mousseau, and Michel Brault. The result of comprehensive research by the curator, Sébastien Hudon, the exhibition includes numerous original photographic prints in small- and medium-sized format, as well as collages using various photographic materials. This corpus, which has remained unknown for no obvious reason, offers a selection of images that is extensive enough to appear exhaustive without overly diluting its artistic quality. It is therefore a clever analogy to use the concept of the “Great Darkness” to refer simultaneously to the obscurantism linked to the historical context of the photographs’ production and to the obscurity that shrouds certain areas of Quebec’s art history.

A related desire to conceive of photography as a visual language on its own obviously inspired these artists, who were drawn to experimentation.

“Photographes rebelles” is one of the few attempts made to date to illustrate the advent of modernism in Quebec art photography by presenting works by artists whose shared purpose was to affirm the specificities of the photographic medium.

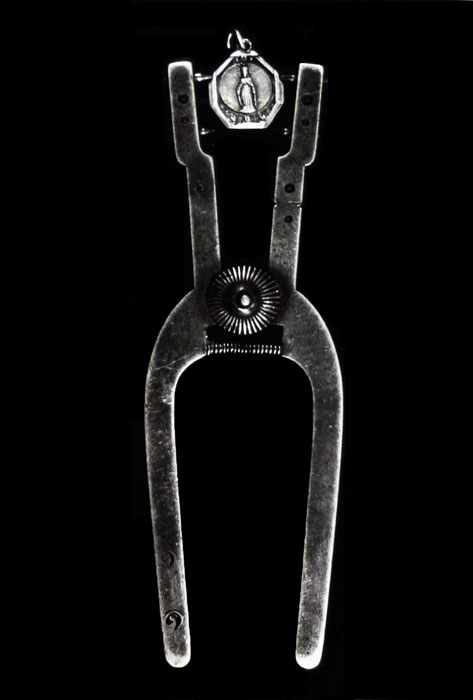

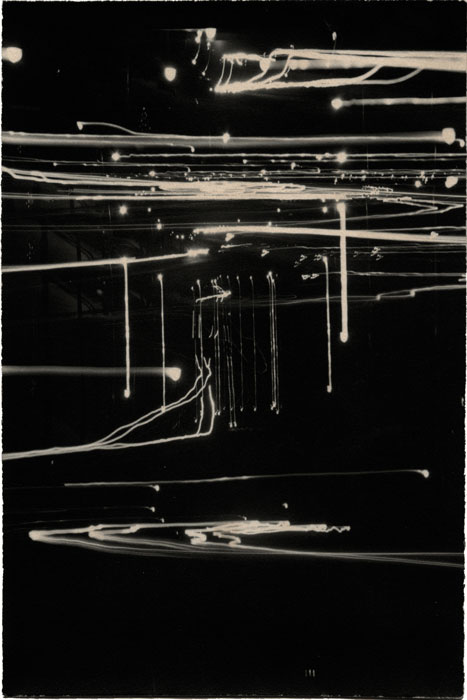

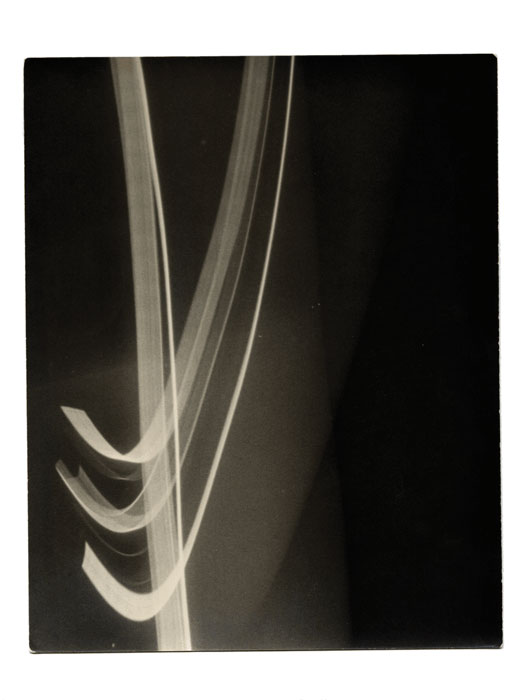

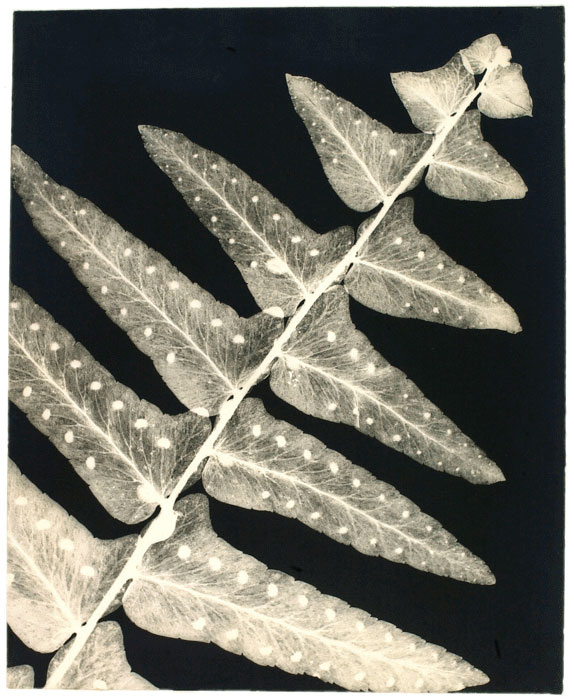

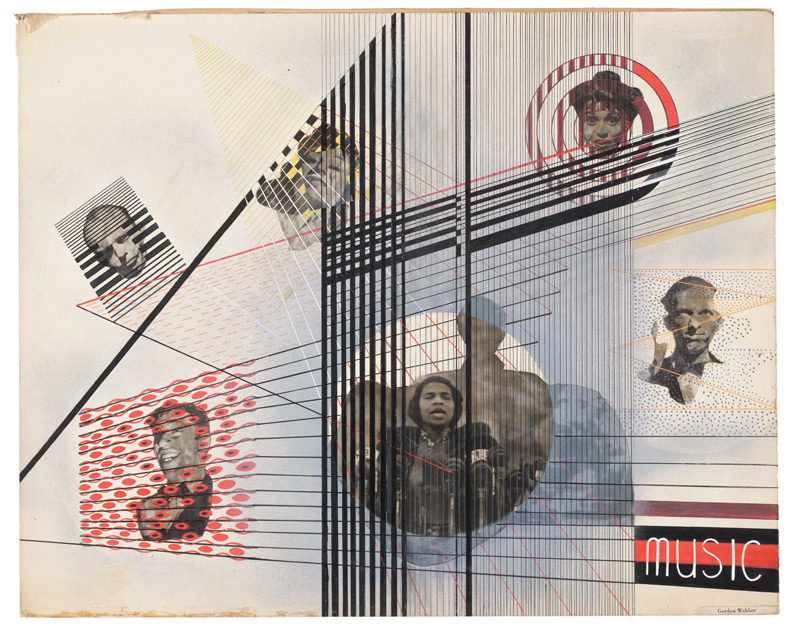

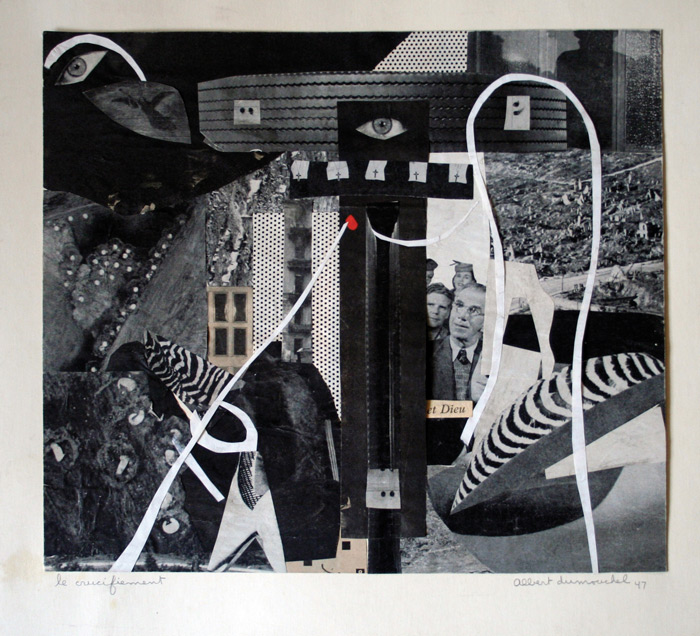

A related desire to conceive of photography as a visual language on its own obviously inspired these artists, who were drawn to experimentation. Thus, the exhibition’s discourse consists essentially of a survey of the visual strategies that they deployed in their effort to free photographic language from the yoke of conventional representation: exaggerated contrasts, dramatic chiaroscuros, overprinting of negatives, unusual framings, macrophotographs of objects, montages and collages, the pictorial use of photographic developer, use of typographic signs, and more. Complementing the diversity of photographic processes is the extensive aesthetic heterogeneity of the body of work on display, which also includes attempts to capture the poetry of the real (notably Brault) and non-figurative experiments exploiting the pictorial qualities of the medium (Dumouchel’s works are exemplary in this regard).

These artists’ works attest to a strong awareness of and sensitivity to certain European pioneers of modernist photography, immediately palpable when one walks through the galleries of Maison Hamel-Bruneau. The ghost of László Moholy-Nagy haunts Omer Parent’s photograms and the luminographs by Jauran, and the spirit of surrealism is immediately identifiable in a photographic exquisite corpse by Mousseau and his acolytes, in Jauran’s revelograms, and in Dumouchel’s non-figurative photographic collages and cliché-verres. Gordon Weber’s low-angle shots are worthy of Aleksandr Rodcenko. However, the hypothesis that these artists were drawing on inter-national art networks for inspiration is not explored in depth in this exhibition, which instead appropriates the usual vocabulary of the history of modern art and, adapting it to the Quebec context, sets out to prove the existence of a Quebec avant-garde hard at work to gain recognition of the artistic value of photography. One previous event, “Photographie 57,” held at the Université de Montréal in the winter of 1957, featured the photographic research of twenty-eight artists removed from the usual aesthetic discrimination of the official salon organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Art.

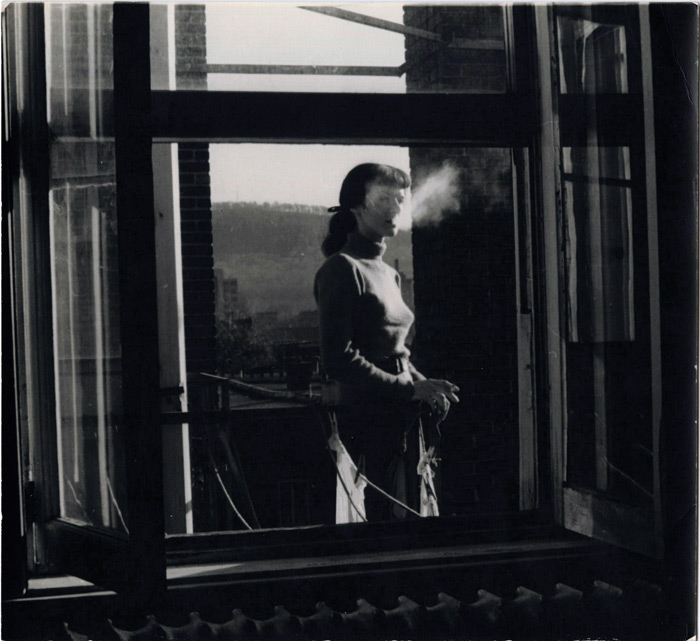

Many of the works presented in “Photographes rebelles” have a historical value that is hard to dispute, either because of their maker’s prominent place in Quebec art history or because of their aesthetic and thematic originality in the Quebec art context of the time. The exhibition brings to light certain images testifying to a particular mastery of composition, including Jauran’s Composition avec Françoise happée par la lumière (ca. 1955) and Brault’s Gilles Groulx et sa compagne s’embrassant au centre du monde (ca. 1960). Among the works most explicitly critical of the conservatism of the era is a photographic collage by Dumouchel titled Le crucifiement, which can easily be understood as a formal attack on the Catholic Church. Finally, one notes the omnipresence of the female figure in the exhibition; the interest of a number of photographers in this subject can be explained as a penchant for eroticism, in deliberate defiance of the morality of the time. According to the exhibition curator, such works expressed these artists’ generalized passion for photographic visuals as much as for the female body, and were part of an artistic stance against the ideological darkness of the period.

Spanning approximately from the beginning of Maurice Duplessis’s first mandate as Quebec premier (1936) to the end of his last mandate (1959), the period covered by the exhibition is only indirectly justified by Quebec political history. Two photographic exhibitions, held before and after the quarter-century covered by the exhibition, form its temporal frame: the first was of works by a Quebec pioneer of experimental photography, Omer Parent, presented in Quebec City in March 1937, at the very time when the sadly famous “padlock law” was being adopted; the second was a show of nudes by Guy Borremans, held in late 1960 and banned by the City of Montreal’s morality squad. The association of these two art events with censorship by the political authorities plays a decisive role in the contextualization of the works presented at Maison Hamel-Bruneau, as it suggests that their production resulted directly from the reaction by the photographers to the political and artistic coercion of the era.

An attempt at demonstrating this thesis is made by juxtaposing “rebel” works against commercial and amateur photographs produced at the time, which act as markers for the “official” art of the Great Darkness. A contrast is thus created between “propaganda” images, characterized by their “impeccable technical quality” and idealization of the moral values of the time, and the experiments of the “rebels,” whose aim was to overturn the “visual codes of ‘art,’ the propagandist, documentary, and utilitarian photography of the Great Darkness.”1 That this formalist opposition stands in for a rigorous examination of the conditions for distribution and reception of this photographic production as a whole is, unfortunately, the weak point of the exhibition. Although many photographs undeniably reproduced the dominant conventions of representation, confining them to the role of vectors of the conservative ideology and morality of the Duplessis era is reductive. On the other hand, as obvious as was the freedom of artistic invention deployed by Quebec artists, this in no way allows us to understand their works as authentic acts of political subversion.

A binary relationship between art and politics is nevertheless inscribed throughout the exhibition. The curator seems to want to situate the production by “rebel” photographers within a well-worn genealogy of modern art that, when adapted to the Quebec context, almost inevitably reproduces the official mythology of Quebec modernity. The exhibition therefore performs a major semantic shift from “modernism” to “modernity.” While claiming to illuminate the advent of photographic modernism in Quebec, it instead promotes a Quebec “photographic modernity,” with theoretical implications that would deserve analysis. In fact, if one sees the invention of photography as an eminently modern fact, one might doubt the validity of such a concept. At best, a more nuanced comparison of all photographic production created during the Great Darkness would have brought to light the different relationships with photography that are presumed by a given time and space, without placing them in a particular order. The decision was made, instead, to present the works of the “rebels” as the production of an enlightened avant-garde putting its art at the service of a struggle against the dominant ideology.

Although one may reproach the curator of “Photographes rebelles” for having encased this magnificent body of work in an overly rigid historical and theoretical framework, one must also,of course, applaud the colossal effort that he deployed to bring this priceless photographic heritage into public view. Finally, the omnipresence of black-and-white photographs not only contributes to the visual coherence of the exhibition but celebrates the past hegemony of a photographic language that is rapidly being marginalized by the advent of digital technologies, as well as an experimental and intuitive approach to photography that we too rarely have an opportunity to appreciate these days.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Art historian Alexis Desgagnés lives and works in Quebec City, where he divides his time between writing, curating exhibitions, and practising photography. His doctoral dissertation was on Russian revolutionary visual propaganda, and his current research concerns primarily the history of past and present photography. He is also coordinator of communications at VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie.