[Fall 2011]

International Center of Photography, New York

January 21 to May 8, 2011

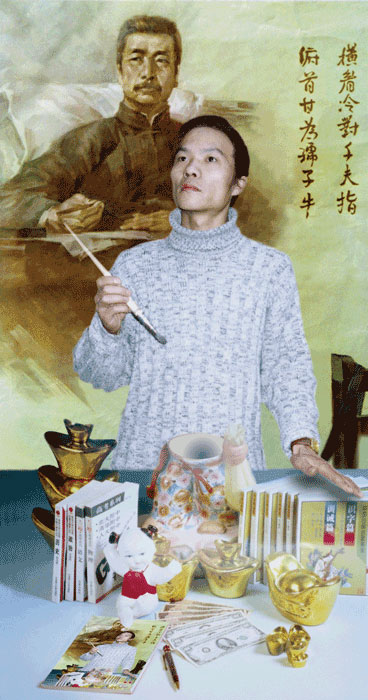

Wang Qingsong’s photo scenarios focus on the ambiguities of China’s changing cultural identity and internal clash of ideologies. Pick Up the Pen, Fight to the End (1997) mimics a late Cultural Revolution poster, Take Up the Struggle of Polemics and Struggle to the End (1975), also on view. We see a girl wearing a Young Pioneers red scarf; Mao’s Little Red Book is on the table. Behind her stands the exemplary left-wing writer Lu Xun (1881–1936). Qingsong’s edgy satirical details include a stack of United States and Chinese currency bills heaped on the table. Forthright becomes forthwrong. Ideologies are as interchangeable as a set of clothing in the global era.

Qingsong’s Follow Me (2003) expresses the basic confusion of early-capitalist post-communist China. Named after a popular English-language tv program broadcast by cctv and the bbc, Follow Me reinvents the meaning of propaganda. A bespectacled teacher points at a huge blackboard, on which random chalk-marked phrases express a confusion of mixed messages. The logos and acronyms express the great changes phrase by phrase, from “Hard currency” to “Nice to meet you.”

Night Revels of Lao Li (2000) imitates a tenth-century scroll by Gu Honyzhong, referred to as Night Revel of Han Xizai. Han was an artist who wanted to reform imperial policy. Discouraged, he reverted to debauched and amusing distractions. The emperor sent an artist to record Han Xizai’s activities in this now-famous masterpiece. Qingsong’s “peasants” are highly charged hipsters in colourful dress with coloured hair. Jack Daniels whiskey, Sprite, and Pepsi Cola are the preferred drinks among these courtesans, some of whom are seated playing flutes. Watching it all, like Han Xiao, the Beijing art critic Li Xianting, who lost his editorial job at a magazine for supporting contemporary art, sits like a sage.

China’s migrant reality is presented in a biting, sardonic photo-critique, Wang Qingsong’s Sentry Post (2002), with its guards, barbed-wire demarcation zone, and “victims” played by actors. Government restrictions of country-to-city migration by the use of official permits are presented by the artist as a war in which people die and suffer and real lives are effectively destroyed by powers that be. Dormitory (2005) shows working migrants who actually made it into the city. As “actors,” the people play their tiny roles oblivious of the collectivity. The mini-activities occur in mini-spaces or spread out into the space in front. It’s Ikea-like, this pure plastic compartmentalized arrangement in which real circumstances circumscribe it all. Dormitory describes a very contemporary “freedom” and space trap.

Unlike Jeff Wall, whose postmodernist staged set-ups have a prescriptive irony, Wang Qingsong directs the scenario with an acerbic, biting edge aimed at identifying the change that China is experiencing. Like many Chinese artists, Qingsong is caught in a cultural dynamic in which Western and Chinese cues are interchangeable. Mixed messages and the relativity of a fusion of global cultural influences can breed new symbolic and iconic clashes in the world of art. Competition (2004), one of the most effective photoworks in the show, is a de rigueur photographic exposé of the mass confusion of China’s reality. Qingsong rented a Beijing movie soundstage for this one, and he papered the wall with handmade posters as if they were propaganda posters. Amid the scaffolding and ladders, this wall is covered with a confusion of hand-painted advertising and logos of corporate and service signology –Starbucks, Camel Filters, Mercedes, Citybank, Michelin – the scale is magnificent.

Tradition becomes the foil for Qingsong’s effective yet subtle critique of Chinese so-ciety in transformation. It’s the beautiful and playful naturalism, the innuendo, and layouts of his “actor subjects” that make it all work. The same style expands in Yaochi Fiesta (2005), in which 160 nude “immortals” relive the Taoist myth that every three thousand years, the Queen Mother of the West celebrates with a banquet. This is Spencer Tunick with an Asian twist, and these immortals are not at all spectacular, more like ordinary people undressed and with nowhere to go amid the fake scenery of boulders, trees, and painted skies. When worlds collide, the change is momentous. Wang Qingsong works the scale of that global change into some remarkably critical, esoteric “documents.” What is true? What is false?

John K. Grande has curated several editions of “Earth Art” at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario. Recent books include Dialogues in Diversity; Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Italy: Pari Publishing), Bob Verschueren Natura Humana (Belgium: Editions Mardaga), and The Landscape Changes (Canada: Prospect/Gaspereau Press). “Eco-Art,” co-curated with Peter Selz, is at the Pori Art Museum in Finland until May 2011. grandescritique.com