[Winter 2012]

by René Viau

Bringing together twenty-six artists under the title Lucidity. Inward Views, the twelfth edition of Le Mois de la photo à Montréal made the theme that served as its title, if not a template for comprehension, the pivot of its articulations. Through the works in this dense, enriching event, a strongly subjective vision was proposed to viewers. For the artists, “interrogating the world goes hand in hand with interrogating oneself (and vice versa),” according to event curator Anne-Marie Ninacs.1

Practising such interrogations, these photographers see the real. At the same time, they force themselves to look deep within the self to find the detachment and freedom of expression that enable them to explain it best. But perhaps we should, rather, talk about “intervals” of lucidity, a little as if the itineraries that are the lot of many of the artists in the event – feeling their way along in the darkness – might lead to both the observation of oppression and the creation of a luminous force to thwart it. This cargo of “clairvoyance” bursts apart the oppression that it opposes.

At Arsenal. Triggering simultaneously an interrogation of the real and a disjointed release of the imaginary in action, Macro Godinho’s video Something White (2008) can be seen as both a metaphor for the photographic process and a form of psychological progression. We follow two men’s arduous journey toward the light. As if they were in a TV reality show, they move through the darkness of a mine or unused tunnel without flashlights. The light that finally appears on the horizon also bathes a strikingly beautiful landscape. Here, the theme of lucidity melds with a Rimbaud-accented poetic consciousness. And, as Arthur Rimbaud wrote in May 1871 in his famous Letter to Paul Demeny,2 the primary condition for this poetry to operate is working on the self in order to “become a seer.” As presented at Arsenal by Douglas Gordon, the catalogue of fears to overcome in order to become at least lucid proves programmatic.

Continuing with this Promethean position, photographer Roger Ballen sees lucidity as a way of stealing or finding fire – that is, capturing the illuminative faculty of visions, sensations, and gestures in order to reconstruct them. Although Ballen borrows from the codes of documentary photography, his settings make us doubt the veracity of his pictures. He intercedes with his models, asking them to help him modify, through their props, their interventions, their own drawings and paintings, the very frame in which they are photographed. Masked faces, birds, Twombly-style tracings, tensions between the fleeting instant and the tragic vision – through these means, Ballen reveals the secret recesses of the soul.

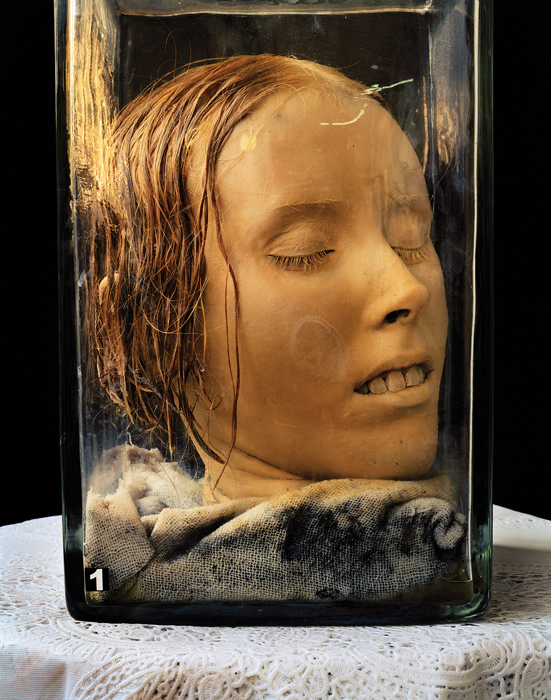

Under the fluorescent lights in Arsenal, after Ballen, a similar stupefaction hits us with Normand Rajotte’s uncertain landscapes. Rajotte is obsessed with photographing nature in a hundred-acre area in the middle of the forest. He isolates and cuts out hundreds of details with the lens of his camera. In these segments of spongy glebe, microcosm meets macrocosm: these samplings oscillate between immemorial landscapes and dives into the mud. Jack Burman’s Memento mori photographs put everything into perspective. Burman haunts morgues and laboratories searching for cadavers preserved in formaldehyde, into which his images curiously breathe an illusory trace of life.

Photograph as Continuum. Death also prowls at the mai, where Juan Manuel Echavarria’s Requiems takes us to Bocas de Ceniza (mouths of cinders), Colombia. The inhabitants of a small village on the banks of the Magdalena River have buried in their cemetery the recovered bodies of victims of drug traffickers. Each villager adopts a grave on which to place flowers. Warding off the endemic violence, the villagers’ compassion helps to reweave the social fabric. With uncommon serenity given the circumstances, the peasants sing moving ballads about the abuses that they have witnessed, and they pay tribute to the victims. They record the presence, even posthumous, of an individual in the world, as if in a portrait or self-portrait. By addressing the question of identity, the portrait form is broadened and transformed as the artist pursues the truth of time and existence.

No more than it is limited to one face, Hans-Peter Feldmann tells us, is a portrait limited to a single being. In 100 Jahre (2001) (the title translates as 100 Years), Feldmann made portraits of one hundred people, one for each year, from a newborn to a hundred-year-old man (in the Dazibao exhibition at the Cinémathèque québécoise). The models pose neutrally, without affectation, in their daily surroundings. Here, the ambition of collecting takes the inverse measure of the apparent simplicity of the intention. Paradoxically, the differences among these people are magnified by the establishment of a category and unit of comparison. The purpose of this well-crafted montage is, in its own way, to signpost and compartmentalize the flow of time. The “grid” accentuates what escapes it: an ersatz life reminiscent of our own lives.

Like Raymonde April, with whom she shares some aesthetic sensibilities, Claire Savoie tries to find, in her video documents, the memory of all of the moments, many of them trivial, that accumulate to form the warp and weft of days, months, years. Luis Jacob (at the McCord Museum), using art as a model, also makes photography into a continuum to be recomposed.

Jim Verburg and, especially, Christine Nunez photograph in the “I” the “me” thus unveiled. Nunez’s self-portraits go beyond the subterfuges of literary self-fiction to approach the psychoanalytic couch and personal diary. Beyond ostentation, for her the self-portrait is not simply an inner game or the construction of a self-portrayal, but a way of self-probing, self-exploration, a way to know oneself better.

Taking account of photography’s ability to isolate and sample details and specimens, Roni Horn, at the UQAM gallery, transposes a form of fixity onto a monumental scale. Her stunning river-wall, composed of the juxtaposition of dozens and dozens of images, paradoxically reconstructs a fluidity that one may have thought had vanished: the presence of the waters of the Thames can be physically felt. Some Thames brings photography of into the realm, in particular, of a series by Claude Monet. The changing movement of light, water reflections, and tonalities are animated, while a more symbolic dimension imbues this imposing cycle.

The question of flow and repetition of images also arises in Kimsooja’s video installation, A Needle Woman (2005), at the Maison de la culture Frontenac. The Korean artist is filmed from the back facing a tide of human crowds, whose thrust is almost palpable. She is framed in the same way in six cities with a reputation for being dangerous or, at least, prey to political agitation: Patan (Nepal); Rio de Janeiro; Istanbul; N’Djamena (Chad); Sanaa (Yemen); and Jerusalem. From one screen to the next, we see the unmoving silhouette of the artist, buffeted by thousands of passersby. She seems immovable, riveted in place, confronting the motion of the masses. Here, the individual, emblematic, is opposed to the multitude, a bit as if this iconic attitude of meditation exhorts us – not in the same way as Stéphane Hessel does in his pamphlet –by her immobile example, to become “engaged.” The tension is even stronger because we see clearly, at the end of the video shot in Sanaa, an action verging on violence: a passerby brandishes a knife at the performer’s back. Like other artists in this edition of Le Mois de la photo – I’m thinking in particular of Rinko Kawauchi – Kimsooja in A Needle Woman brings a certain whiff of Eastern religion.

Symptomatic of certain attitudes advanced in this edition of Le Mois de la Photo at the Centre clark, Whose Utopia by Coa Fei testifies to a desire for de-alienation. To begin with, video artist Coa Fei documents the daily life of workers in a Chinese light-bulb factory. After showing the production line, Coa Fei highlights what seem to be breakaways. The camera confers an identity, an individuality, upon the workers, as their gestures take on an aesthetic aspect. These low-paid workers obviously savour a time to stop and meditate, perhaps a form of homeopathic work stoppage? Facing the dominance of economic logic, Coa Fei wonders if utopias are possible today. Although tiny, utopia is exposed by Coa Fei and Kimsooja along the way, welded both to the quotidian and to its mobility. With these icons of resistance to cynicism, Kimsooja and Cao Fei are able to bring sharply into focus a crucial form of topicality concerning our era, in which the theme of “lucidity” is fully legitimized.

More than a Pretty Title. Diane Borsato also examines the notion of micro-utopia by associating it with her own experience. With an intimate take on lucidity, Yann Pocreau produces a haunting reflection. Occupying the field of the visible, the body, placed before the light, espouses a situation of physical fragility and imbalance. Alphonso Arzapalo mimes, with his body, certain physical characteristics of the public space. Here, the tone is turned down a notch. It is true that transposing the intention inherent to the title of the event is not without risk. One such risk is that of abolishing the autonomy and individuality of each work, even though in its logic the mounting of Le Mois de la Photo exhibitions, disseminated on so many sites, is based on the works’ propensity to share, or not, similar preoccu-pations depending on whether they are shown in one context or another.

However, some works remain strangely silent with regard to the notion of lucidity. At Concordia University, Jesper Just’s work, for example, is associated with this common denominator only by marshalling all the resources of a theme that, with its double statement – “lucidity” and “inward views” – casts a wide net. With his deconstruction of cinematographic codes, we are far from lucidity seen as “the wound closest to the sun,” the words by poet René Char that inform and synthesize my completely personal perception of a slightly nebulous premise. That is, the term “lucidity” may provoke a certain degree of perplexity. But, more than a pretty title, or a symptom of vague or otherwise all-encompassing directions, “lucidity” can be understood, rather, as a project, an ambition, a keynote.

It is not that in “playing” Jesper Just, the curator is trying to write a score of her own devising. What becomes obvious, quite simply, is the capacity of this artist’s films to shine with their own clarity. In this sense, such works, by illuminating the whole, give a clear idea of the limits of the theme’s grasp.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Known as The Seer Letter.* The following artists were also featured in the twelfth edition of Le Mois de la photo à Montréal : Gemmiform, Massimo Guerrera, Corine Lemieux, Augudtin Rebetez,

Lisa Steele, and Kim Tomczak.

René Viau is a journalist an art critic. He has contributed to numerous publications in France and Quebec. He conducted an interview with Jocelyne Alloucherie published in the monograph Œuvres choisies 2004–2009 (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2009).