[Winter 2012]

by Alexandra Martin

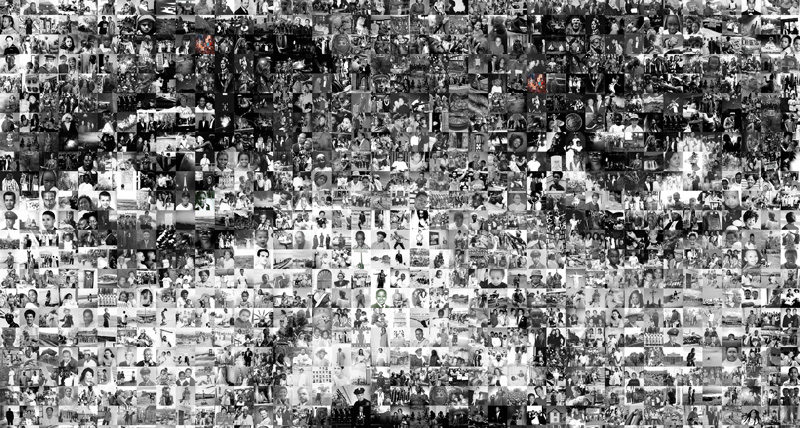

In downtown San Francisco, at the corner of Mission and Third streets, is a huge picture window before which passersby can stop to look at a photo-mosaic several metres high inspired by the famous portrait Girl from Tamale (1973) by Chester Higgins Jr., which is also one of the “tiles” in the mosaic. If they wish, they can enter the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) to take a closer look at the mural.

The Face of the African Diaspora is the icon of MoAD, which opened in December 2005. Its mission is to showcase “the history, art and the cultural richness that resulted from the dispersal of Africans throughout the world. By realizing our mission MoAD connects all people through our shared African Heritage.”1 Of course, showcasing the diaspora is a major museographic challenge. First, how can its profoundly dynamic nature, unquestionably imbued with mobility and fluidity, be accommodated within the fixed space of the museum? As researcher Brandy W. Catanese, suggests, the display strategies employed to contain the cultures of the diaspora within the walls of a permanent exhibition give rise to a tug-of-war between static and dynamic forces – opposed forces that, ironically, are found in a single space representing a single subject2. To get past these contradictions, which are inherent to its very nature, MoAD turns away from the fixed material culture that museums usually deal with. Rather than concentrating on the quality of the object, MoAD has turned toward human beings and their personal life stories to show the living culture of the diaspora. The words of the museum’s first executive director, Denise Bradley, have been quoted many times in the museum’s press releases and on its Web site: “MoAD is truly more than a museum of objects, it is a museum of people and their individual journeys and stories.3” Moreover, MoAD did not come into existence, as do most museums, to house a collection. The concept of diaspora guided its creation.

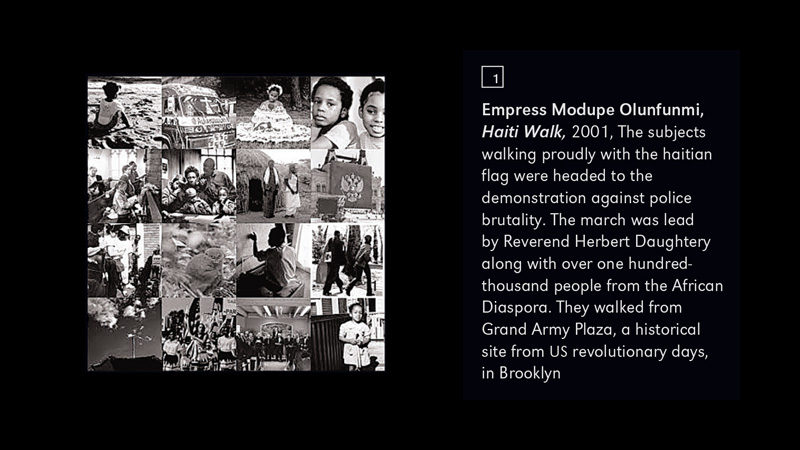

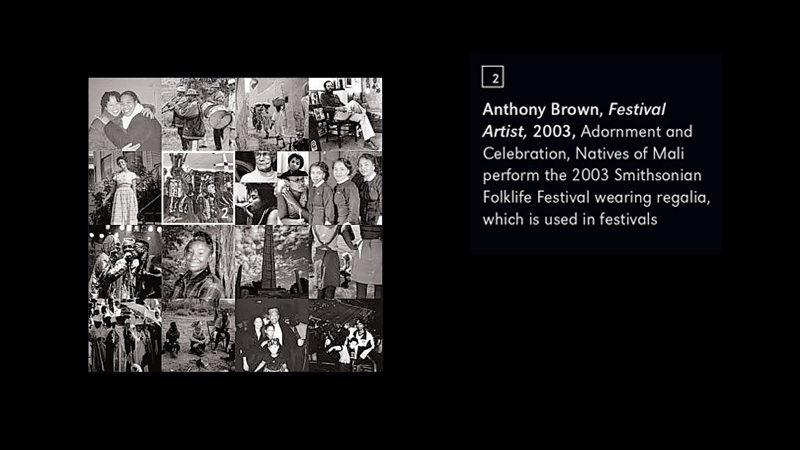

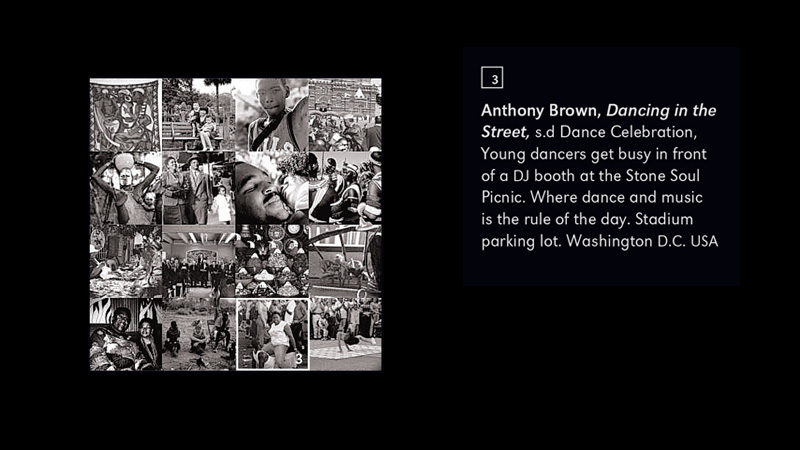

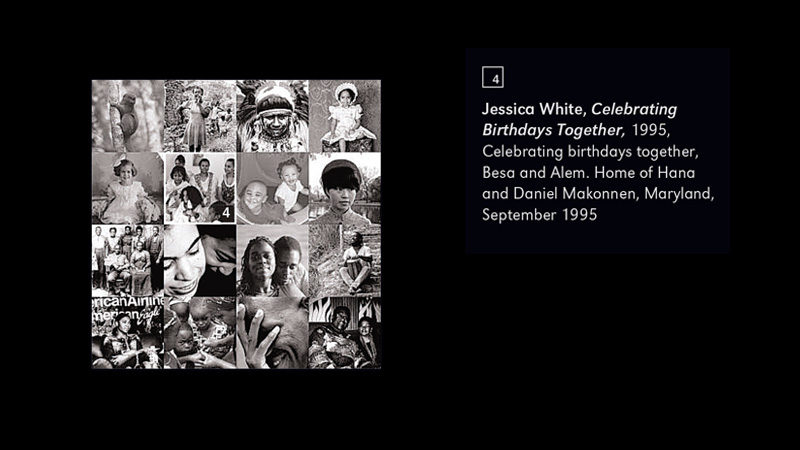

The Face of the African Diaspora represents MoAD’s first act of collection. If we look at the work from a distance, we see only the portrait of an African girl. But as we approach, the true nature of the work is revealed: it is in fact made up of more than two thousand photographs, mainly portraits. These thousands of images were sent to the museum in response to an international public appeal for photographs, open to both amateurs and professionals, made before MoAD opened. The institution received photographs from every continent, although the majority came from African countries, Latin America, the West Indies and, of course, the United States. Most are contemporary, although a few date from the early twentieth century. The photomosaic shows different life scenes, with people, alone or in groups, participating in an activity. Among the people portrayed are some well-known figures – artists and politicians, including San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, who was the instigator of the MoAD project4 – but most of them are unknown.

Some of the photographs were taken during major events, such as weddings, birthdays, baptisms, graduation ceremonies, wakes, or festivals, while others were taken during the course of the everyday life of the people appearing in them: a mother and daughter at home, children at school, parents with their newborn baby, teenagers breakdancing in the street, and so on. There are also more static portraits. The sepia-coloured photomosaic makes one think of a family album, since these are very personal pictures. The human subject is central. On the other hand, not all of the portraits are self-representations; some were taken, for example, during a trip, and the individuals were unknown to the photographer. Most of the people portrayed are of recent African ancestry. But, although most are from black communities of the diaspora, we also see different faces, for the work is intended to affirm that “while our faces may be different, our stories may be different, and our journeys may be different, our origins and our destiny are shared.”5

The museum tries hard to show that “despite the ethnic and cultural differences that separate us, we are linked, through our ancestors, to Africa, and thus we are all part of the African diaspora.”6 About this work with two stories, Higgins himself said, “The captivating photograph of the Girl from Tamale, Ghana, used in the foyer of the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco is meant to convey how all of us in the African Diaspora are connected, one to another, in the divine spirit of the African Continent, personified by the quiet dignity of this young African child.”7

It is not unreasonable that a photograph by Higgins was chosen to compose a portrait of the African diaspora, for he devoted his work to the subject. Indeed, “Much of Higgins’ imagery is inspired by his quest to re-define the visual document as it relates to people of African descent. Over the past five decades, he has produced six books reflecting a sensitive and in-depth diary of his explorations of the human Diaspora, and his concern with his own humanity.”8 These books include Black Woman, Drums of Life, Some Time Ago: A Historical Portrait of Black America (1850–1950), and Feeling the Spirit: Searching the World for the People of Africa.

The Face of the African Diaspora is MoAD’s signature artwork because it conveys the institution’s values, which are about individuals and their life stories. In fact, each photograph sent to the museum had to be accompanied by a short text that gave it context and introduced its author. Like the photographs, the life stories and biographies now belong to the museum’s embryonic collection. In the view of MoAD, it is more correct to speak of a virtual collection, in which the Web site occupies the position of a visible vault by presenting each of the images and excerpts from the related texts.

This way of doing things brings MoAD into a current of thought that is quite new in the history of museum practices: that of sharing of authority between the museum and the community.9 This desire to present the public point of view is reflected in what is called the “new museology,” in which attention is brought to bear on the transformation of relationships between experts and the public. The guideline for cultural institutions that subscribe to this movement is to state their role and social relevance. The approach taken by MoAD, through the creation of its photomosaic, represents an effort to have the community interpret itself. The museum thus aims for a rapprochement between itself and the diaspora.

The photomosaic is considered the core of the group of works exhibited, as it displays MoAD’s twofold mission. First, the museum honours the art, culture, and history of communities of the black diaspora throughout the world and highlights its contributions, which are too often pushed to the edge of official history – both American and global. Second, it wants to highlight the common origins of humanity. It is transforming the diaspora into a universal subject that is accessible to everyone.10 We can now be involved with a conceptual category that draws not on the upheavals and traumas attached to the experience of uprooting, but to a current of thought that celebrates unity and equality among peoples. Thus, the diaspora is understood as a space of affiliation and not alienation.11 The Face of the African Diaspora is anchored in an anti-racist logic; it tries to create a sense of belonging among visitors so that they will appropriate MoAD’s messages.

However, this anti-racist logic is a bit inconsistent. The museum would like to break with the idea of a culturally homogeneous African diaspora to show the diversity hidden behind it. Although initially the museum wanted to deconstruct certain myths about this subject, it has unintentionally obliterated the negative experience that is attached to it. As James Clifford has recalled, the diaspora is articulated both positively and negatively.12 An example of positive articulation is present in the process of identification with global historical cultural forces, of which Africa is a part. Here, the idea is to feel not so much African as “global.”13 But the photomosaic does not succeed in presenting a complete portrait of the diaspora because it does not convey the experience of discrimination, exclusion, and displacement that it entails. By taking only its positive aspects, the museum subscribes to an optimistic, overly naïve version of history.

The romantic vision of a neoliberal discourse on multiculturalism, in which difference is standardized and signposted, and in which diversity becomes the characteristic trait of modern societies, is the MoAD vision. In this multiculturalist perspective – manifest beyond museums – difference is dissolved and alterity is consumed, usually by elites.14 The construction of these new hybrid identities is “founded on the inclusion of differences within the self. . . . Differences of this type do not endanger those who appropriate them. They are digested, integrated into the spaces of cosmopolitan life.”15 Despite its good intentions, MoAD homogenizes the experience of the diaspora, which becomes synonymous with general human experience. In the end, one may wonder if the black experience is itself marginalized in such a context, even though when the museum project began the intention was to celebrate it. Furthermore, it must be noted that the globalized orientation of MoAD went hand in hand with the city’s demographic situation. In a San Francisco that is becoming more and more bourgeois, in which the black population has been in decline a number of years, the MoAD’s “post-racial” policies and poetics of representation cannot help but evoke, as Catanese observes, “a black San Francisco of the mind rather than the body, appealing to a universal diasporic subject because the local subject is frustratingly out of reach.”16

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Brandy W. Catanese, “‘When Did You Discover You Are African?’ MoAD and the Universal, Diasporic Subject,” Performance Research, vol. 12, no. 3 (2007): 91–102.

3 Museum of the African Diaspora, Setting the Stage for MoAD (San Francisco: MoAD, 2005); Museum of the African Diaspora, http://www.moadsf.org/ (consulted 15 December 2009).

4 In 1999, San Francisco mayor Willie Brown gave a mandate to create a museum devoted to presenting and disseminating the city’s African-American culture. At first, the museum was expected to be an African-American museum, but after the museum committee met several times, it was decided that it should have a broader orientation and be dedicated to the African presence in the United States and the world.

5 Museum of the African Diaspora, Setting the Stage.

6 Museum of the African Diaspora (2009). Audio guide text, French-language version (our translation).

7 Chester Higgins Jr.: Forum-Questions, http://www.chesterhiggins.com/forum-questions.html?-MaxRecords=25&-SkipRecords=25&-SortField= recordnum&-SortOrder=descending&-Op=bw&category=questions&-Op=bw&active=yes (consulted 10 November 2011).

8 Chester Higgins Jr.: Photography, http://photographs.chester higgins.com/pages/1/About/About/ (consulted 10 November 2011).

9 On museums and community, see Sheila Watson (ed.), Museums and their Communities (New York: Routledge, 2007); and the Smithsonian trilogy: Ivan Karp and S. D. Lavine (eds.), Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington, dc: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991); Ivan Karp et al. (eds.) Museums and Communities: the Politics of Public Culture (Washington, dc: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992); and Ivan Karp et al. (eds.), Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations (Durham, nc: Duke University Press, 2006).

10 Catanese, “‘When Did You Discover.’”

11 Ibid.

12 James Clifford, “Diasporas,” in Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 244–77.

13 Ibid., 256–57.

14 Jonathan Friedman, “Culture et politique de la culture : une dynamique durkheimienne,” Anthropologie et sociétés, vol. 28, no. 1 (2004), 23–43. 15 Ibid.

15 (our translation).

16 Catanese, “‘When Did You Discover,” 102.

The Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) is a not-for-profit organization situated in downtown San Francisco and contributing to the city’s economic and cultural revitalization. Since it was opened, in December 2005, MoAD has become a cultural focal point along with its neighbours, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Zeum, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum. It is one of the few museums in the world devoted exclusively to African culture and its diaspora, presenting cultural objects of the peoples of Africa and their descendants from around the world.

Alexandra Martin holds a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in museology from the Université de Montréal. Her research interests include representation of minority groups in museums, the formation of ethnic identities, and inter-group relations.