[Winter 2012]

by Sylvain Campeau

For a number of years, Patrick Dionne and Miki Gingras have been working on large-scale photographic projects that encourage artistic engagement in society. In 2002, to better fulfil this mission, they founded Diasol, a charitable organization the objective of which is to use art photography as a means of intervention with marginalized people and young people and adults with difficulties with school or family, in psychological distress, or in the process of social reintegration. It was in this perspective that they designed the Identité project, the final step of which was creation of a huge mural composed of the images that people had been asked to take of themselves with a Brownie camera transformed into a pinhole camera. To date, Dionne and Gingras have produced an artwork with the population of Montreal North, and they are hoping to do the same with people in the Côte-des-Neiges and Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhoods of Montreal.

Montreal has not been the only site for these projects. Dionne and Gingras have conducted similar experiments in Latin America. Humanidad was an important first step. In Nicaragua, they organized art workshops with the country’s child workers. They were assisted and supported by INPRHU-PANT and Dos Generaciones, Nicaraguan organizations promoting the right to education, health, and entertainment for child workers in different markets and at the La Chureka dump in Managua. Young people learned how to use pinhole cameras made with recycled materials, with which they produced photographs of their surroundings. The final result was quite successful, as the images were shown in numerous exhibitions. Nevertheless, it seemed to Dionne and Gingras that the context in which the images had been made should have been, in one way or another, presented more concretely instead of being part of a sort of “beyond-the-image” and “beyond-the-scene,” and thus having to be explained aloud or in accompanying wall texts.

For many years, Miki Gingras and Patrick Dionne have worked on large-scale photographic projects that encourage a closer relationship between the artist and society. In 2002, they founded Diasol, a cultural organization whose objective is to use photography as a means of intervention with young and marginalized people. The projects Investigation (2005), Vision poétique (2006), and Partages culturels (2008), produced, respectively with adolescents, sellers of the newspaper L’Itinéraire, and young people in Montréal-Nord, were based on learning how to use a pinhole camera and portrayal of social themes. More recently, the Identité project involves creating enormous fresco murals made from community portraits. Three murals have been produced to date in Montreal neighbourhoods: Montréal-Nord, Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, and Côte-des-Neiges; a fourth is underway in Centre Sud. Montreal has not been the only site for these projects. Gingras and Dionne have conducted similar experiments in Latin America between 2004 and 2008. Humanidad was an important first step. In Nicaragua, they organized art workshops with the country’s child workers. They were assisted and supported by inprhu-pant and Dos Generaciones, Nicaraguan organizations promoting the right to education, health, and entertainment for child workers in different markets and at the La Chureka dump in Managua. Young people learned how to use pinhole cameras made with recycled materials, with which they produced photographs of their surroundings.

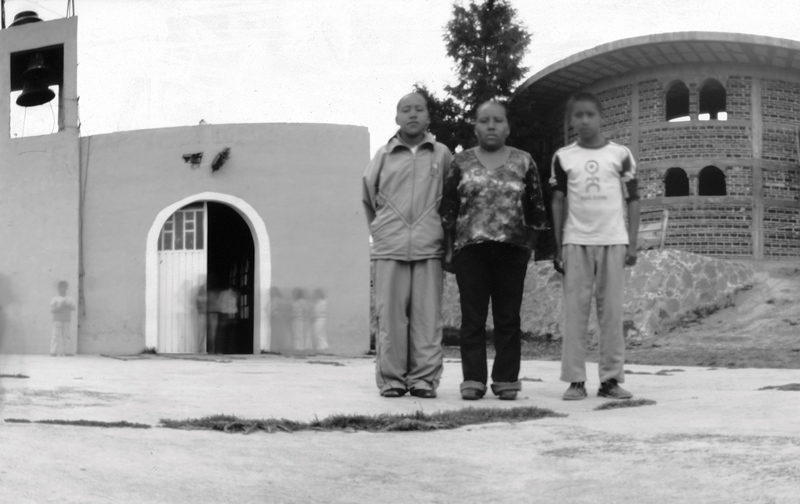

The final result was quite successful, as the images were shown in numerous exhibitions. Nevertheless, it seemed to Gingras and Dionne that the context in which the images had been made should have been, in one way or another, presented more concretely instead of being part of a sort of “beyond-the-image” and “beyond-the-scene,” and thus having to be explained aloud or in accompanying wall texts. With Escenarios de Mujer, a solution to this problem was found. Again, the project consisted of providing supervision and minimal training to a specific group of people. This time, it was women in San Pedro Ecatepec, a Mexican village in the district of Atlangatepec, state of Tlaxcala, near the American border; because of its location, it is almost totally devoid of men, who have left to seek their fortune with Uncle Sam. Through discussions and meetings, it was agreed that the women would create images representative of their state as women. Gingras and Dionne provided assistance by conducting two seminars a week. Working with pinhole cameras made with cans, the women produced images, often with long exposures, for which they chose the parameters. The photographs were developed in a rudimentary darkroom set up in the village; then, the selected images were enlarged onto canvas with a procedure that gave them an old-fashioned magenta tint. During the village festival, the images were exhibited on the walls of the houses where their makers lived and a map was distributed so that people could make a full tour of the exhibition. Then, Gingras and Dionne took digital photographs of the project, concentrating on the images selected and exhibited, completing the documentation and information on how the women approached the project.

And what was their approach? What can be said about it? One thing emerges immediately, and that is the unique dialogue that this way of working initiates with the documentary genre. For, of course, these are documents, although they could be described as self-documents made with assistance. In effect, the expertise that went into them is an expertise that has been transmitted – or, perhaps, borrowed, as the intervention of the photographer-mentors was indispensable to their creation. Moreover, the raison d’être of photo-documentary is transmission of information on a state of the world; it is not important whether the information is transmitted as pure illustration or maintains a more informative relationship with the doxa. In the context of the approach exhibited here, the images made by these women have more to do with revelation and formation. For, in the end, the images resulted from a desire to illustrate the self to the self and depended on the introduction of two mentors into the world in which the women were living. And this is another factor to be elucidated! Documentary photographers do not want to be intrusive.

In the most naïve historical sense, they wanted to be non-invasive, simply witnesses, and their presence on the scene was not supposed to influence the course of events. We know today that this was pure utopia! Gingras and Dionne decide to provoke and follow what may be compelling and formative about the taking of pictures. They fully assume the power of retaking the photograph that comes from subjecting oneself to its influence. Someone who sees herself may know herself better! And someone who chooses an image of himself, one that he creates and puts forward, enters a sort of stage of the enlightening mirror. In creating and controlling their image, people somehow re-create themselves. The pictures that Gingras and Dionne finally create and bring back from this formation toward the self-image reveal an experience of lived sociability. They are related, among other things, to the high point, the final result: the exhibition. From this starting point – the social, community, and cultural action – viewers are invited to learn about what has taken place there. They have before them the documents of that experience. They witness the work of bringing relationships to light, and they also see in these images the different steps that led to the final experience: training, taking pictures, choices, discussions.

But the essence is not here, in the moment that closes the circle. The essence is in the exhibition that is the result of these women’s work, as it was proposed to them by Gingras and Dionne. Here, in their own village, before the people who are their friends and family and whom they have known their entire lives, the images will bear witness to a proclaimed and reclaimed uniqueness. They will operate as markers of the self, as an experiment of creating self-awareness through images, the display of what they see themselves as being. There is, here, both knowledge and recognition in the pride of being and the dream of being seen in the most distinctive portrait of oneself. Similarly, by walking along the path on the map, going from house to house, viewers see themselves through these known places and evoke the familiar strangeness of the women who had the experience of creating an image of themselves and creating themselves in an image. And so it happens that these self-documents, whose final arrangement becomes an exercise in shared sociability, awakens people to the fact that the community makes the individuals that compose it at least as much as they make the community through their social ties, for which photography has here become the linking symbol.

One could, no doubt, raise the objection that this practice of the self-image, the self-portrait, is not new and that it appears a bit pretentious to create an entire new category for it – the “self-document.” Self-portraits, however, are made by artists searching for introspection – as were the women that Gingras and Dionne recruited, of course – but in the secrecy and privacy of their personal world and artistic approach, with neither invitation nor training. They come to it on their own! This is not the case for the women of San Pedro Ecatepec, who were encouraged to undertake a similar practice. They responded to an invitation for creative sociability. This leads us to navigate in the waters of relational aesthetics. At the beginning of Nicolas Bourriaud’s book on this subject1 are inspiring words that unfailingly bring to mind the work by Gingras and Dionne. Art is a “state of encounter”;2 it takes “for a theoretical horizon the sphere of human interactions and its social context”;3 it “holds together the moments of subjectivity linked to unique experiences”4– experiences that are also shared, of course, but that, above all, encourage “a culture of interactivity that proposes the transitivity of the cultural object as a fait accompli,”5 proposing the artwork as “a point on a line,”6 representing the lived experience of sociability.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Ibid, p. 18.

3 Ibid, p. 14.

4 Ibid, p. 20.

5 Ibid, p. 25.

6 Ibid, p. 21.

Since 1999, Patrick Dionne and Miki Gingras have jointly created photographic works that focus on political, social, and cultural issues. In 2001, they founded Diasol, an organization whose mandate is development and dissemination of creative projects that encourage artists’ engagement with society. Most of their projects involve collaboration with local populations, in both Canada and Latin America. Their best-known work is Humanidad, les enfants travailleurs du Nicaragua. In 2007, they founded the FueraDFoco collective in Mexico City, in collaboration with two Mexican artists. They received a grant from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec for a studio-residency in Mexico in 2011. Dionne and Gingras live in Montreal.

Sylvain Campeau has contributed to numerous magazines, both Canadian and European (Ciel variable, ETC, Photovision, and Papal Alpha). As a curator, he has organized thirty exhibitions presented in Canada and abroad. He is also the author of the essay Chambre obscure : photographie et installation and of four books of poetry.