[Winter 2012]

Suzy Lake

University of Toronto Art Centre

April 30 to June 25, 2011

In general, the art world is not kind to older women artists. Nan Goldin recently gave an interview in which she was brutally frank on the subject. She remarked that three-quarters of the art world wants her dead; her work has changed, but the market would rather have the Nan of yore: documents of seedy underbellies and demi-mondes. Now that she has the life perspective of a woman in her sixties, her hard-won ease does not square with the woman the art world wants her to be. Suzy Lake has made this harsh truth the core of her work. But then again, this is not a recent development. In some sense, a version of this truth has been central to Lake’s practice from the very beginning, when Goldin was still an art student. What Goldin speaks of, and what Lake iterates throughout the span of her practice thus far, is the essential feminist struggle: how to be a woman in the world (art or otherwise).

To call Lake a feminist is at once an obvious truth and a simplistic reduction. It’s not merely that she is a feminist; in looking at the range of her output, one understands that she has made her career understanding feminism from the inside out. Since the very beginning, she has used herself as the magnifying glass under which femininity is deconstructed and reconstructed. Moreover, the construction of femininity is always a game played on shifting sands: one doesn’t finally arrive at womanhood (or manhood, for that matter); its contours slip and shift with age and the passage of time, and Lake has always been vigilant (ever the mark of a good photographer), surveying the terrain and adjusting her footing accordingly.

The work that comprises Lake’s show “Political Poetics” at the University of Toronto Art Centre, curated by Carla Garnet, is a good first step in considering the broader corpus of Lake’s output. Her work of the early to mid-1970s ignited the flame that has kept her burning all these years. In these photographs, she enacts a complicated performance. She revels in high artifice, an obfuscating theatricality that is sometimes made formally literal, as in the Genuine Simulation series (regrettably absent here): the make-up that is applied to the photograph simultaneously obscures her face and re draws it; its opacity both obliterates the black-and-white face printed on the paper, and re-presents it in lurid cosmetic-counter colour.

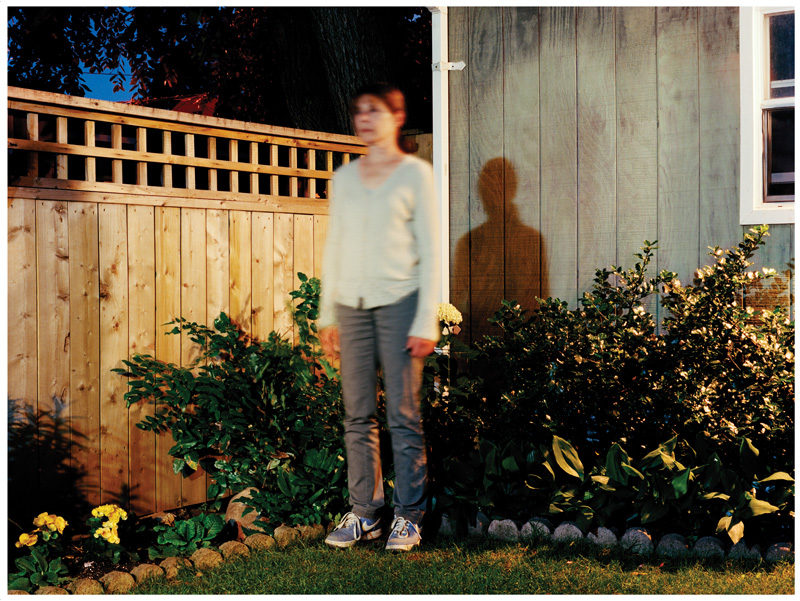

Similarly, the poses and the gestures that are catalogued in On Stage are almost comically artificial; certainly, they have almost nothing to do with any kind of mundane vernacular gesture. Or, perhaps more accurately, just as the make-up job in Genuine Simulation represents a face assembled by cosmetics, the women of On Stage are recyclings of women’s media images: the pouty gamine of fashion photography, the sultry silver screen siren, and so on. In performing these women, Lake is not only reflecting back the fun-house mirror distortions of media-prescribed femininity, she is implicating herself in that distortion as well. These photographs meld interiority and presentation; she is simultaneously reflecting and exposing, using the camera as both surgical tool and amphitheatre. With these works, Lake masters this paradoxical photographic praxis, and it forms the basis of everything that is to follow. This double-gaze permeates her work, and it takes various forms and tones: the frantic, almost masochistic violence of Choreographed Puppets; the psychological compressions of Impositions; the gentle satire of Peonies and the Lido; the autumnal austerity of the Extended Breathing series. Under Garnet’s curatorship, “Political Poetics” posits woman as an alchemical self-reflexive process: osmotic absorption problematized by analytical engagement.

As she ages, Lake’s reflection of femininity – her own, and that of her cohort – has become darker, less playful. Gone are the puckish trappings of On Stage; Reduced Performing, the most recent work at utac, looks almost as if Lake is measuring herself out for a grave. This premature morbidity (à la Nan Goldin ?) is too easy a reading, however: yes, Lake is immobile, stretched out on her back, staring blankly at the viewer; but the contrast of her bright clothes against a stark white backdrop announces her presence boldly, and announces further that, though it seems as if Lake is going gently unto that good night, this is merely yet another performance. Lake tackles the presumed invisibility of older women with an affirmed, acidic presence, not only in the form of her Technicolor garb, but in the unmistakably wry smile that she sports; womanhood is an ever-changing process, and Lake and her camera are by no means done with their dissection.

Sholem Krishtalka is an artist and writer. He holds a bfa from Concordia University, and an mfa from York University. His writing has been featured in Canadian Art, c Magazine, cbc Arts Online, Bookforum, among others. His artwork has been featured in Carte Blanche 2: Painting, a survey of contemporary Canadian painting. He had a solo show in Brooklyn, New York, at Jack the Pelican Presents; most recently, he has had solo shows at the Art Gallery of Peterborough and the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.