[Spring/Summer 2012]

by Pierre Rannou

When we enter the exhibition space at the UQAM gallery, what we see first are two television screens with headphone sets, and then we see two more screens on the wall to the right. As we continue to look around, we note the large-format photocopies of newspaper front pages on two of the four walls and, standing alone on the left side of the exhibition space, a pedestal on which a book sits. The presentation method of the grouping is quite classic. It is obvious that the artist has rejected the garish: she has refrained from playing the seduction card or creating spectacular displays. This straightforward presentation requires us to be serious. We can sense the artist’s desire to make us think. And yet, no explanatory text is offered, nothing suggests what path our visit should take, no wall cards identify and distinguish the elements. How are we to comprehend the intention of Nadia Seboussi, an Algerian artist completing her master’s degree in visual and media arts at UQAM, to investigate “the use, function, and ethics of the journalistic image during the Algerian civil war (1990–2000)”? This civil war (the “black decade”) between government forces and various armed Islamist groups broke out following the cancellation of elections in 1991. As confrontations intensified, some groups of belligerents no longer limited their attacks to the army or police but began to attack civilians – first the lay elite, in the form of targeted assassinations, and then the general population, mainly by conducting raids on isolated villages.

… the artist wanted to decode the production and dissemination of images of assassinations… By encouraging photographers to speak less about the events than about their relationships with them, Seboussi separates the idea of objective construction of documents…

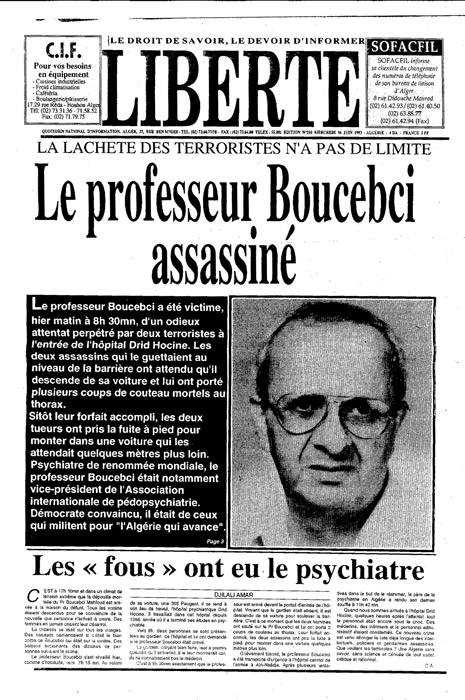

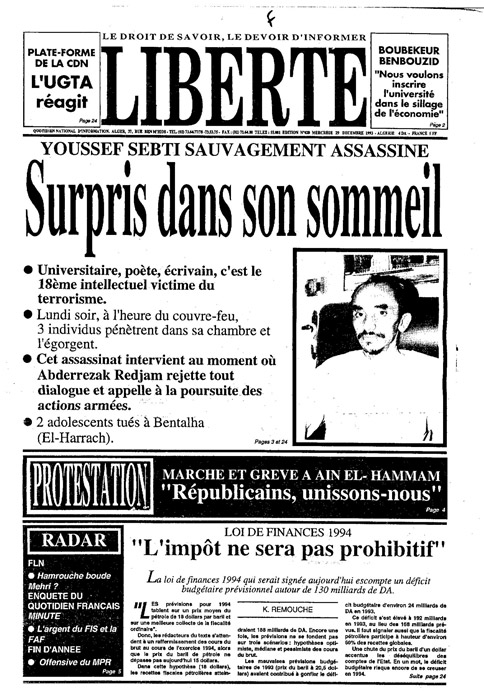

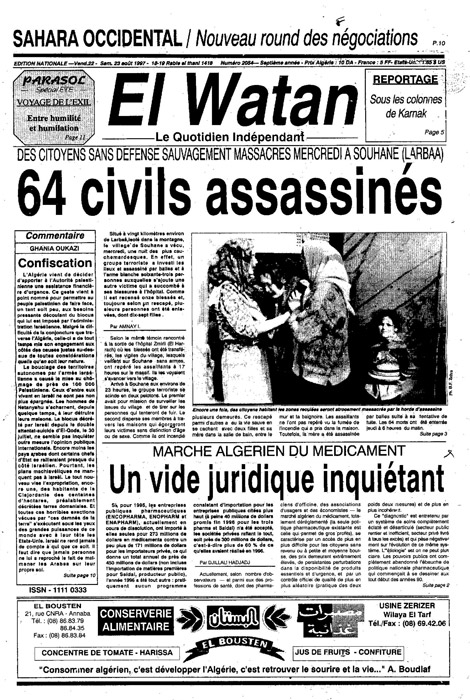

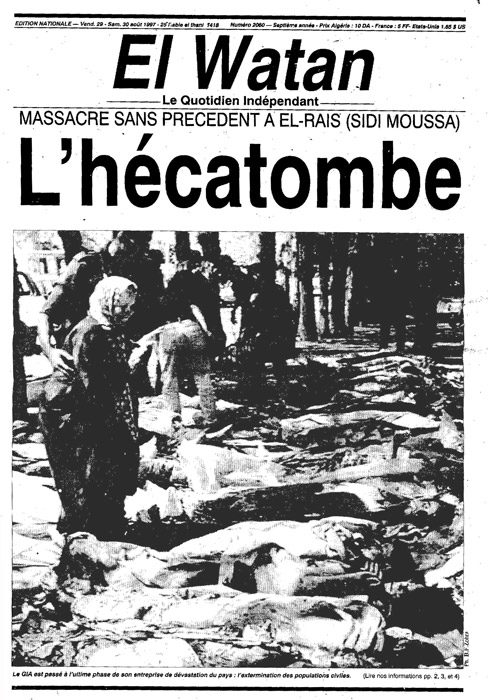

Display. A series of twenty different front pages from Algerian dailies (El Watan, Liberté, Le Matin, La Tribune) published during the black decade are hung in chronological order. Then, we find a group of fifty photocopies of front pages, also hung on the wall in chronological order, many of which repeat the subjects addressed by ones that we have already seen. The role of these photocopies in the overall layout is not immediately and clearly perceptible. The content makes us think that it is a simple contextualization enabling us to grasp the exhibition’s intention. In a way, we are reproducing our usual relationship with a newspaper front page – that of obtaining information – without really questioning how it works. When we look at the last element in this series, we observe that La Tribune used the same photograph above the fold three times (22 September, 3 August, 14 October). This revelation encourages us to reconsider these documents. When we look again, we perceive how the use of the photographs changes. There is a transition from portraits of murdered notables to illustrate headlines to pictures of cadavers that aim to convey more directly the violence of the assassinations, thus privileging horror and spectacular images over the text and reducing the pages to sensational formulations. By choosing to reproduce these front pages in the form of photocopies, Seboussi refuses to give them the value of artefact, although she doesn’t deny their role as archival documents. Rather, she emphasizes their ephemeral character, restating their status as reproducible mass-consumption objects. Furthermore, the hanging system chosen, which consists of pinning them directly to the wall, unframed, encourages us to perceive them as objects to which little value should be attached.

Reception. It is the opposite with the book placed on a pedestal and accompanied by white gloves so that we can touch the book without damaging it; it appears to be a unique, very important object. This document contains seventy testimonials by members of the Algerian diaspora, gathered by the artist in response to her request to identify the photographic or media image produced at the time of the conflict that struck them and to describe its impact on them. Among the images mentioned most often are those of the explosion at the Houari Boumediene Airport, the assassination on Boulevard Amirouche, the Madone de Bentalha, and the assassination of President Mohamed Boudiaf. When we read the answers, we realize that a great number of them are not about the photographic or media images, but about lived experiences, personal anecdotes, or images of trauma, giving the grouping a very subjective character.

Production. The interviews conducted with the Algerian photographers Souhil Baghdadi, Zohra Bensemra, Louiza Ammi, and Hocine Zaourar, who worked during the black decade, also have an eminently subjective nature. At first glance, these interviews, presented on screens attached to the wall, are about documenting the practice of photojournalism during the civil war and establishing the working methods in effect at the time. Although the viewing order is not prescribed, the content of the different videos seems to indicate that it would be best to start on the left and then proceed to the right, thus passing from general considerations to more direct questions on practice or aesthetic approach. The questions, which appear as intertitles, are not necessarily the same for each photographer; some are repeated and others are not. The four videos, however, have similar openings, which raises the idea that this is, if not a single discourse, at least a single discursive unit. Although Seboussi preserves the uniqueness of each interviewee and is discreet on screen, she gives form to her own discourse through the editing of the tapes and their arrangement in the space.

In asking them to describe their first contact with violence or the emotions experienced in the field, Seboussi reveals an often-obscured aspect of photojournalists’ work. When, for example, Bensemra relates that during the murder on Boulevard Amirouche, she continued to photograph even though she was crying, we understand a bit better the difficult reality in which these photographers were immersed. As Ammi and Zaourar note, they remain human beings, experiencing all sorts of emotions and uncertainties, even as they are expected to make images that report on situations.

Although it is mainly the feeling of having to act as a witness – to preserve traces so that a history of the decade may eventually be written – that keeps them going, they have to ask themselves what images to make. The moment of conflict seems to be propitious to ethical questioning, but because the photographers are continually shaken by events, they more often find themselves making aesthetic choices. To escape the temptation of showing decapitated bodies and pools of blood, each developed formulas and an angle of attack. Bensemra and Ammi looked for the details that would make all ofthe atrocities comprehensible (Hocine, for his part, spoke of tight framing) or took a specific point of view of the scene, whether through the gaze of women (Zaourar) or that of children (Ammi). But in all cases, as Souhil Baghdadi explains, there is no question of speaking of good or beautiful photographs.

Exhibition Layout. In light of these intentions, we are less surprised, as we walk around the exhibition space, to find no photographs hung on the walls. We can easily understand that the artist wanted to decode the production and dissemination of images of assassinations under the cover of supposed journalistic objectivity. By encouraging photographers to speak less about the events than about their relationships with them, Seboussi separates the idea of objective construction of documents from a reflective gaze at situations. Through her insistence on this type of information, she enables her interlocutors to reappropriate their lived experience and indicate the wounds that almost-daily coverage of the assassinations left on them. Similarly, by refusing to single out the testimonials by Algerians that did not deal directly with the media images and including them in her collection, Seboussi has chosen to opt for a human approach, a possible encounter of subjectivities. This way, the staggering of front pages of different Algerian dailies ends up less producing a clear idea of the context than underlining how each news-desk editor appropriated texts and images to reproduce his or her own subjectivity. This way of performing the decoding is the truly original aspect of Seboussi’s approach, as she played adroitly on the layout of the different elements in the exhibition.

A Doubly Significant Title. The exhibition takes its title from the unfinished novel by the Algerian intellectual Tehar Djaout, but this choice goes far beyond simply an homage to this author, who was murdered in 1993 during the conflict. It indicates Seboussi’s position regarding how information is treated. Of course, taken literally, the title, Le dernier été de la raison (The Last Summer of Reason), indicates the end of an era and the beginning of a world in which madness reigns, in which good sense seems to have gone missing. It is equivalent to directions for how to read the elements on display. But if one considers it in the light of the book from which it was borrowed, it instils at the very heart of our visit to the exhibition the idea that the artist, like the character in Djaout’s book, has chosen to resist the rise of fundamentalisms through a critical spirit and through culture, the true form of citizen engagement.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Quotation taken from the artist’s specifications outlined in the installation, in which he explains her project to her correspondents.

Critic and art historian Pierre Rannou also is an exhibition curator. He has published essays, book chapters, exhibition texts, and magazine articles. He teaches at the Department of Cinema and Communications and the Department of Art History at Collège Édouard-Montpetit.

Nadia Seboussi was born in Algeria; she has lived and worked in Montreal since 2002. With the exhibition Le dernier été de la raison (2012), she is completing the requirements for her master’s degree at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) with the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. She has received a number of grants and awards, including the Prix Pierre-Ayot and the 2009 Bourse Jacques de Tonnancour 2009 for her academic career.