[Spring-Summer 2012]

Songs of the Future:

Canadian Industrial Photographs 1858 to Today

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

20 August 2011 to 3 June 2012

The landscape tradition in North American photography extends back into the colonial era. In “Songs of the Future,” photography is an instrument that documents the unfolding of an industrial heritage. Some of the flavour of this show is akin to Gordon Lightfoot’s song Canadian Railway Trilogy, but, sadly, no images of Chinese or Irish workers or of Sir William van Horne figure in it. The evolution of Canada’s resource industries is as fascinating visually as it is historically. Studios such as William Notman’s and Alexander Henderson’s were synonymous with the development of Canada as a country. A series of Notman albumen stereographs of the building of the Victoria Bridge in Montreal between 1854 and 1859 are nothing if not fascinating. This was, after all, the longest iron bridge in the world at the time, and it was inaugurated by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, in 1860. William Notman was right in there documenting it all. Richard Maynard’s scenes of the bridge building and canyons of British Columbia have a clarity and depth of field that recall Carleton Watkins’s scenes of the opening up of the American West.

Edward Burtynsky’s railway photographs taken in the Canadian West, such as CN Track Thompson River #002 (2008), from the Rail Cuts series, continue in that tradition. His works parallel those of another onetime Montreal photographer, Mark Ruwedel, who now works in California. What would have enlivened this show would have been Burtynsky’s overview shots of the oils sands in Alberta featured in the Globe and Mail. What strikes one in this tame version of Canada’s untamed development legacy is any curatorial or visual editing (or could I say consciousness?) to provoke awareness of the errors and trials that development and disruption a dizzying and dirty development and disruption of the land have produced. We are now producing a dizzying and dirty development legacy currently underway in Canada, produced by a very corporate not at all Canadian corporate grab. The one hint at this in the show is Geoffrey James’s powerful Black Lake, Quebec (1993) with its sinuous black and gradated lines of mine tailings from Canada’s asbestos industry. Why are there no photographs by Bob del Tredici (author of The People of Three Mile Island) documenting Canada’s involvement in providing radium and uranium for the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or of the Aboriginals who worked in mines in Saskatchewan (and later died from the effects)? Without question, such incredible documentary photographs of Canada’s nuclear industry should have been in this show. Del Tredici, who was co-founder of the Atomic Photographers Guild, is a visual cataloguer and documentary photographer with a conscience. In a post-Fukushima world, such photographs are topical and timely (and largely not seen in an era of conservative, politically correct museological curating), particularly in a show addressing Canada’s industrial and colonial heritage.

Roy Arden’s Landfill, Richmond, b.c. (1991), with its sparse tree and solitary telephone pole, is both so stark and so picturesque that it almost looks like a post-media Group of Seven landscape! Isabelle Hayeur’s chromogenic print Jade (2004) from the Model Homes series (2004–07), with its image of a suburban house in mid-production, captures the current state of creation/production in the post-developed world with a keen anthropologist’s eye.

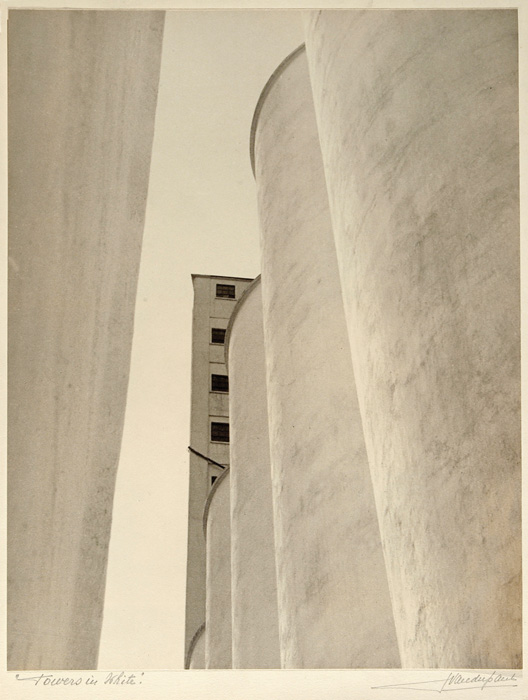

What makes this show interesting is the regional cross-country balance of imagery. We see J. C. M. Hayward’s series of Anglo Newfoundland Development Company in Grand Falls, in which the construction of a pulp mill in 1905 is accompanied by logging and building documents. Hayward’s Wood Pile (1912) exposes economies of scale in the same way that Burtynsky’s Oxford Tire Pile, California (not in the show) does for our times. Both make landscapes out of human activity, the subject of this show. Alexander Henderson’s albumens (1872–74) of construction of the bridges on the Miramichi capture structures at the point of being built as they interface with Canada’s always incredible natural scenery. These photographs are fascinating for their exposure of the growing nature-culture divide in the developing Dominion of Canada. Like John Vanderpant’s classic gelatin-silver print No. 2 Towers in White (ca. 1934), Montrealer Bill Vazan’s Visual Sphere from Jacques Cartier Bridge (1975–77) is more art for art’s sake, a visual and perceptual dialogue with structures that uses the bridge as a point of departure. Vazan’s photograph is in the same league as Dieter Appelt’s Forth Bridge series consisting of eight large-scale photographic panels exhibited at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 2005 and now in its collection. With a more progressive and dramatic sense of Canada’s incredible industrial history, this show would have been a must-see.

Photographs of industry in the land with no social and political context makes for an intriguing informational history of Canada’s great and continuing industrial heritage. Like the lions at Trafalgar Square, centre-point of all that colonialism was or could be, “Songs of the Future” is a show that “looks good” but whose claws have been removed.

John K. Grande is the author of Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Pari Publishing, 2008). He recently co-authored Bob Verschueren: Outdoor Installations (Editions Mardaga, 2010) and contributed to The New Earth Works (isc Press, 2011). He recently co-curated “Eco-Art” with Peter Selz at the Pori Art Museum in Finland. Art & Ecology is being published in Shanghai in 2012.