[Spring-Summer 2013]

Archival Dialogues:

Reading the Black Star Collection

Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

29 September to 16 December 2012

Curator Peggy Gale and Ryerson Image Centre director Doina Popescu smartly chose to inaugurate Ryerson University’s new building and gallery with an exhibition specifically about “The Archive.” In this case, the focus was the world-renowned Black Star Collection, comprising over 290,000 photojournalistic prints, which had been donated anonymously to Ryerson University in 2005. This was a smart choice because it engages the practice of looking back that has become popular with artists and curators. In his essay “The Way of the Shovel,” published in a 2009 edition of e-flux journal, Dieter Roelstraete argues that our culture’s obsession with “the New” has led to the rise of forgetfulness, a condition handily taken on by art: “Art has doubtlessly come to the rescue, if not of history itself, then surely of its telling: it is there to ‘remember’ when all else urges us to ‘forget.’” In the exhibition Archival Dialogues, Popescu and Gale understood the contemporary relevance of the historical image, while seeking to retain the notion of the archive as a whole. Eight significant Canadian artists – David Rokeby, Michael Snow, Vic Ingelevics, Vera Frenkel, Stan Douglas, Stephen Andrews, Marie-Hélène Cousineau, and Christina Battle – were commissioned to create a work “in dialogue” with the collection, and a strong curatorial hand led viewers to examine and appreciate the archive not only as a historical document, but also as a reflection of their own relationship with history. Three artworks serve to acclimatize the viewer to the idea of looking. David Rokeby, whose digital piece Shrouded graces the impressive New Media wall at the building entrance, created a near-perfect start to the show, replacing the usual didactic texts with the viewer’s own revelation as each clouded image was gradually revealed, hands first, then backgrounds, then faces. Finally, the image flipped around to show the back of the photograph, filled with notes and explanations. It was a delight to recognize a young Mick Jagger and quite sobering to see revealed clearly terrified Vietnamese civilians in their war-torn country.

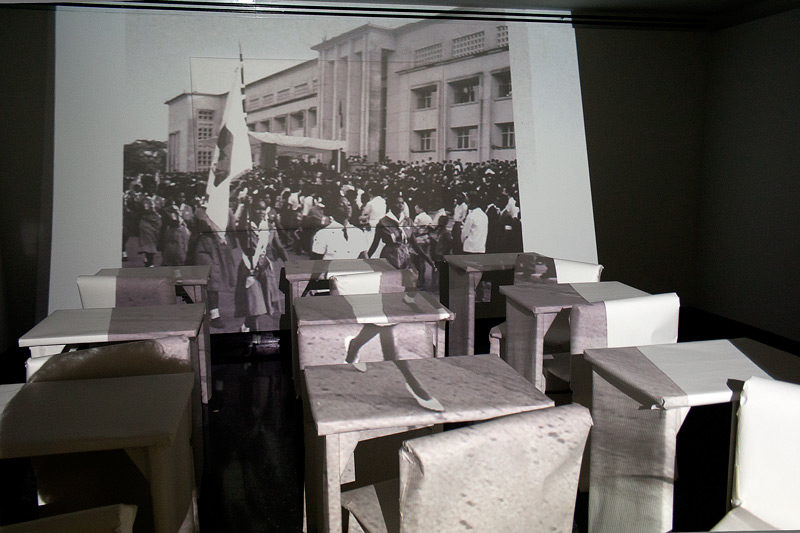

Michael Snow’s video TAUT was an admirably simple and effective installation in a room just outside the gallery entrance. Elementary-school tables and chairs and a blackboard had been covered with photographic paper, upon which images were presented, as if by overhead projector. One by one, photographs of crowds appeared, with no explanation. Viewers were free to imagine the questions asked by schoolchildren and were reminded of the artist-teacher, whose gloved hand holds each image. Across the hallway was a poetic meditation on the archive by Vid Ingelevics. Prints – one of Pierre Elliott Trudeau – were being scanned, organized, and filed. At one point, large prints were even ripped up, reminding viewers of the complex nature of copyright but also of the diminishing status of analogue photography. Inside the gallery, three more works dominated. The strongest was Vera Frenkel’s video-photo-text installation Blue Train, inspired by several train journeys associated with the collection. A video projected on a big screen recounted her mother’s fraught escape by train to Paris during the Second World War with her infant daughter. Because of the inclusion of imagined sound “memories” by other passengers – a nurse, a midwife, a German soldier – viewers became witness to a kind of history. One imagined the memories as one’s own, filtered through the experience of the artist and of the photojournalist Werner Wolff, whose image initiated the artwork.Another standout piece was by Stan Douglas, whose gorgeously staged large-scale photographic installation Midcentury Studio Project, inspired by his study of postwar photojournalists – including those in the Black Star Collection – snapped to life when arranged by Popescu and Gale to form a loose narrative, weaving between truth and fiction, coupled with the collection’s images upon which they were based.

Marie-Hélène Cousineau, a Montreal-based producer and director who is intimately familiar with Arctic life, contributed a straightforward installation, Perdre et retrouver le Nord (Losing touch and coming home) that brought a distancing, museum-like quality to the show. Cousineau selected Peter Thomas’s 1960s images from Baker Lake and rephotographed them, with the original subject now holding the earlier print. She coupled these images with three lovingly handmade dollhouse-sized replicas of Inuit residential interiors designed to illustrate the Westernization of Northern domestic life over time. Stephen Andrews’s installation juxtaposed a series of wall-mounted photographs of Lee Harvey Oswald just before he was shot – you could feel the moment’s intensity – with a film that blended fragments such as the famous image of Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, who burned himself alive in Saigon in 1963, with some of Andrews’s own to create a dark, moody narrative. Similarly, Christina Battle trod the line between truth and fiction, pairing “real” Black Star images with her own, and drew an otherworldly story from one that itself blurred the real and imagined – the mysterious “Mothman” sightings in West Virginia in 1966. Each of these works negotiated individual memories and interests, but together they demonstrated that history is a useful and important medium that, when brought into the present moment, has much to teach us about ourselves. This particular archive is a valuable tool indeed.

An expert on contemporary art, architecture, and design and the founder and publisher of one of Canada’s most widely read culture blogs (viewoncanadianart.com), Andrea Carson Barker is a writer and critic who works with various culture organizations on strategic profile building, PR, and social media planning. She is founding curator of the daily art auction artbombdaily.com and sits on the City of Toronto Public Art Commission.