[Spring-Summer 2013]

Bonnie Rubenstein has been a director at CONTACT since 2002, and the festival’s artistic director Originally from Toronto, she holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. As curatorial assistant for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, she worked on several groundbreaking exhibitions. In 1989, Rubenstein relocated to England to work at Lisson Gallery London as director of special projects, a role that included the organization of Anish Kapoor’s exhibition at the 44th Venice Biennale in 1990. She then coordinated international exhibitions, publications, and public art commissions for Kapoor, and worked with a number of prominent artists.

by Jacques Doyon

Jacques Doyon : Would you first give our readers the story behind the creation of CONTACT? Who created the festival? What gave the impulse? What was the context then, and what were the original goals?

Bonnie Rubenstein : It was Stephen Bulger who inspired the idea for a photography festival in Toronto. He founded CONTACT in 1996 along with three other gallery directors: Darren Alexander,

Linda Book, and

Judith Tatar. Their goal was to develop a greater appreciation of photography and to unite what appeared to be just a small community in Toronto at the time. CONTACT began as a grassroots initiative open to anyone who wanted to participate. The founders envisioned having about twenty participating venues, but, to their surprise, there was quite a lot of interest from the very beginning. The first festival in 1997 included fifty-six exhibition venues of all sorts – from a small café to a large institution such as the Art Gallery of Ontario – and featured more than a hundred photographers whose work spanned the field. We now have more than two hundred venues and present photo- based work by more than 1,500 artists, but we still maintain the broad range that was established in the early days. The Open Exhibition component continues to stimulate alternative shows and events across the city, and this is the foundation upon which we continue to build our curated programming.

JD: Would you give us an idea of how the event developed and strengthened its thematic focus over the years? And tell us a bit about your own involvement in the shaping of this focus, and about how the themes are chosen?

BR: For the first six years, CONTACT had a very strong focus on education but was an umbrella organization for exhibitions produced by our participants. I was hired by the board of directors to develop a critical focus for the festival, based on my international experience. I didn’t have an extensive background in photography, but advice was always close at hand; Edward Burtynsky, for example, has been instrumental. The festival faced many challenges then, but there was great support from the community to take it to the next level. We didn’t have our own exhibition venue so, drawing on my interest and previous experience with public art, I developed the public installation program, which launched in 2003 with photography in subway cars, in transit shelters, and on street billboards.

We introduced the annual theme in 2005 to establish a critical structure and focus for a growing number of curated projects. That same year we began working with the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA) to co-present an exhibition highlighting our thematic focus. The theme began as a conversation with a range of people in the community, and it continues to be informed through dialogue with artists and photographers, colleagues, committees, the board, curators, and educators. This collaboration is an essential part of developing thematic programming that has relevance to our participants and our audience. The theme is also informed by what’s going on in the world – not just in the art world, although, of course, that’s an important component. The concept for the theme usually develops before we start programming, and at times one year’s theme has inspired the next. There have also been instances where the theme has emerged out of the desire to show a particular exhibition.

JD: The festival appears to be well rooted in the Toronto community, and also in the broader photography community here and abroad. Would you give us an idea of the different activities and collaborations that the festival has undertaken and strengthened over the years to broaden the position and reception of photography?

BR: The growth and success of our curated programming is very much a result of collaborations with the community and support from a wide range of contributors. Since 2003 we have produced more than eighty public installations throughout Toronto. These take place in a wide range of public spaces and on the streets, in the subway, and at the airport. Our billboard projects extend to six cities across Canada.

We continue to present a primary exhibition at MOCCA each year, and it is in many ways a central focus of the festival: we hold our launch party there and it’s a great place for a huge celebration. We continue to build the scope and scale of our thematic exhibitions; this year, there are ten in total, thanks to the vital and productive relationships that we have developed with different institutions over the years [the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Art Gallery of York University, the National Gallery of Canada at MOCCA, the Ryerson Image Centre, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Toronto International Film Festival, the University of Toronto Art Centre]. Together we have organized exhibitions of works by Canadian and international artists, a number of which have attracted enormous interest here and abroad. Although we focus our energy on producing the festival every May, some of our exhibitions have travelled within Canada and Europe. These growing international relationships also shape our programming; this year, we pre-sent the North American première of three exhibitions organized in Europe.

JD: Would you say that knowledge and recognition of the photographic practices have changed drastically since the festival’s inception? Has attendance at the exhibitions broadened? Are the media more attentive to your initiatives?

BR: Yes to each of the above, without a doubt. There are many factors that demonstrate the enormous growth and expanded interest in the festival over the last seventeen years. The field of photography has changed dramatically during this time, and so has the way images are created and consumed.

CONTACT has become the largest photography festival in the world, and this is measured in several ways, including audience size (over 1.9 million visits in 2012), number of exhibitions (around 200), and number of participating artists (over 1,500 annually). Our local and international audience continues to grow each year. Even with little spending on media in 2012, the festival received more than 500 million media impressions from press coverage, based on official monitoring statistics, and this is equal to a $30 million media campaign!

JD: Would you introduce us to this year’s theme of the festival and its main exhibitions? Tell us why we shouldn’t miss the event.

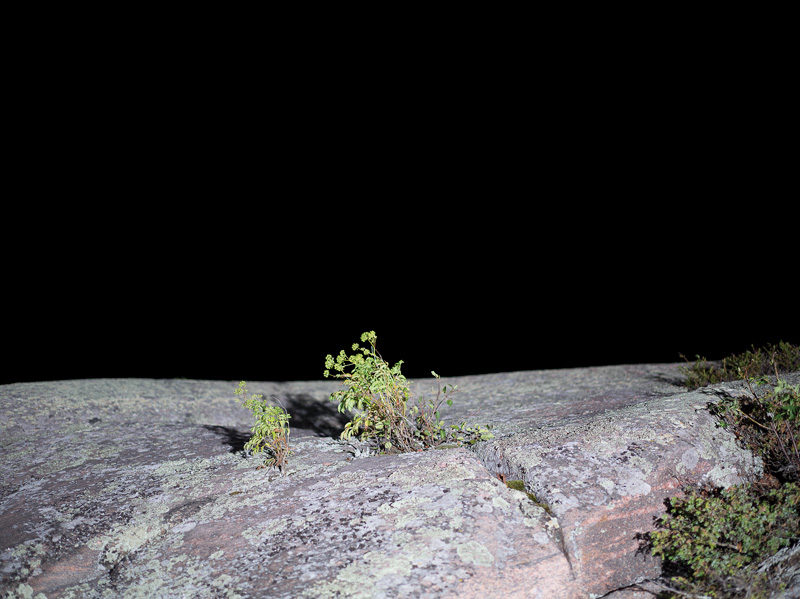

BR: The 2013 festival theme, Field of Vision, frames our primary exhibitions and public installations and positions photography as an extension of vision. The notion that the camera’s field of view extends the eye’s field of vision is central, as is the concept of creative imagination – the ability to conceive an exceptional idea, image, object, or circumstance through photography. Some of our exhibitions expose people and places that are rarely seen by humanity, whereas others imagine aspects of our physical environment that do not actually exist. A number of shows are the result of expansive, long-term investigations, brought together through years of perseverance by their makers or custodians.The North American première of Sebastião Salgado’s exhibition Genesis at the ROM is his most ambitious series of photographs. Captured over the course of eight years of travel (2004–11), these majestic photographs reflect the expansive range of Salgado’s journey in search of near-pristine places around the world, which most of us will never see. The exhibition Collected Shadows at MOCCA provides a rare glimpse into the collection of the Archive of Modern Conflict, an exceptional yet elusive organization that is based in London, England, and Toronto. Over two hundred photographs spanning the history of the medium were drawn from the archive’s holdings of over four million images. The result is a compelling examination of our world that draws attention to how the meanings of photographs shift and change over time. For the exhibition 24hrs in Photography, Erik Kessels downloaded approximately one million images that were uploaded to the Internet platform Flickr over a 24-hour period. Approximately 350,000 images will be positioned within the CONTACT Gallery, overwhelming visitors with piles of photographic prints. Kessels demonstrates how Internet users are bombarded with images on a daily basis and reveals how the limited frame of a computer screen can present an expansive view of the world. At the University of Toronto Art Centre, we’re presenting the first survey of Andrew Wright’s work, Penumbra, which highlights his interest in perception and photographic technologies. Although Wright’s approach is often quite experimental, even playful at times, his highly refined works reflect a rigorous practice that invites us to reconsider the ways we visualize our world.

This year’s public installations challenge the way we perceive and interact with our physical environment, raising questions about the role of photography in society. Focusing on the site as both influence and subject, several projects are site-specific commissions. We asked Martin Parr to focus his lens on Toronto, and he selected Pearson International Airport as the venue to present a collection of images based on his ongoing interest in travel and globalization. Travellers will encounter over 180 of Parr’s large-format images of food documented in Toronto and around the world. For the atrium at Brookfield Place in Toronto’s financial district, we commissioned James Nizam to adapt the approach that he developed for his Thought Form series. Working at night, he manipulated light using mirrors to construct the shape of a pyramid. Existing only as a photographic document, Nizam’s work is hung precisely where the isometric projection was captured.

These are just a few of the many exhibitions and installations that we are presenting this year, which highlight the importance of images as means to better understand the past, the present, and also perhaps the future.

Jacques Doyon has been the editor-in-chief and director of Ciel variable since January 2000.