[Spring-Summer 2013]

By Emmanuel Hermange

Dominique Auerbacher’s early career was bound up in the emergence of photographic commissions devoted to landscape in Europe, starting with the Mission photographique de la Datar, which brought her to the public eye in the mid-1980s. She sparked a lively debate by choosing, against all expectations, to photograph a number of major European cities as part of a project on Lyon, in order to highlight a degree of homogeneity among major urban centres. Through commissions and other projects, such those devoted to exploring the world of Ikea through its catalogue (Fauteuils and Catalogue Pieces, 1995), she developed a reflection on the notion of shared places by examining the link between landscape and territory – the latter now overdetermining almost totally, in her view, the gaze on the former. As part of her wide-ranging research on urban graphic cultures, Scratches continues this reflection by featuring tagging as a vector of the gaze “in” the city, or a form of inscription that paradoxically asks, using a resolutely wild gesture, about what is shared in the public space. Although tags, like graffiti, are now often exhibited in galleries and museums and their aesthetic is copied in all sorts of commercial media, public opinion and the authorities continue to speak of “vandalism” when tags are produced in their original environment, outside of the sites that developers sometimes devote to them in the urban space.

Since the wall fell, Berlin has become, in a way, Europe’s laboratory on twenty-first-century urbanity, as all phenomena seem to be magnified there. In 2007, while living in the German capital, Auerbacher became interested in the inscriptions and collages whose unique inventiveness, diversity, and density give the urban space the appearance of a diffuse and discontinuous forum, as these gestures and graphic forms seem to reach out and respond to each other. After shooting a large number of snapshots – taking notes, as she puts it – she created a first grouping of twenty-seven photographs titled Kunst ist Waffe (“Art Is a Weapon,” 2008), in reference to anonymous posterings on bus shelters displaying this statement followed by the name of its author, German playwright Friedrich Wolf, who published a short essay under this title in 1928. Defending, in opposition to the bourgeois concept of “art for art’s sake,” a Marxist conception of the relationship between art and society, Wolf stated, “The writer who does not see the tragic conflicts of today on our streets, who is not seized by them and overpowered – he has no blood in his veins! He sees the world from his writer’s studio or through the dusty windows of his church; but he does not forge ahead into hard, wild, rusty, unadorned life, of which art today is a part!”1 Auerbacher wished to put this conception of art and of the role of the artist to the test in the present day by undertaking a large-scale project on the burgeoning of graphic forms within urban cultures. Analysis of her “notes,” of which Kunst is Waffe is a preliminary selection, led her to distinguish five aspects in this urban material that became five distinct groupings of images, among them Scratches, which she completed after presenting Nachstücke (Pieces of Night produced with Holger Trülzsch), an installation of 160 images revealing the wild state of some deserted pockets of the city (Nosbaum & Reding Gallery, Luxembourg, 2011). The three other groupings – Ornements urbains, Assemblages collectifs, and Psyché urbaine – are in the process of being created. By speaking of not “series” but “groupings,” Auerbacher underlines certain aspects of her working method, which consists of leaving the selection and organization of these images open and in motion.

As part of her wide-ranging research on urban graphic cultures, Scratches continues this reflection by featuring tagging as a vector of the gaze in the city, or a form of inscription that paradoxically asks, using a resolutely wild gesture, about what is shared in the public space.

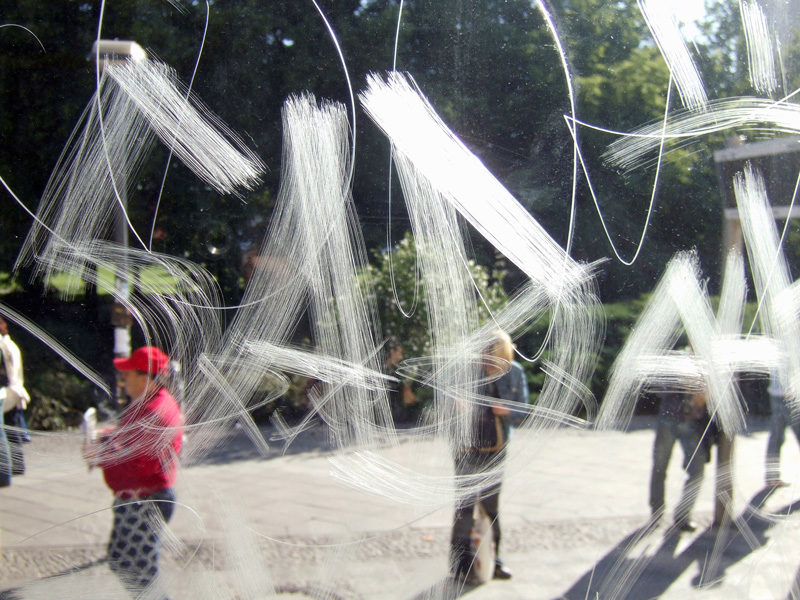

An unusual escalation of tagging on Berlin tramcar windows was the inspiration for Scratches. Auerbacher chose this term for its onomatopoeic qualities as much as for the link that it suggests, within hiphop culture, between the tagger who acts furtively, using improvised sharp tools2, and the scratching technique used by rap DJs to accelerate or slow the rotation of a vinyl record on a turntable, making the sound of the needle scratching on the surface of the record as if by vandalism. The intensified accumulation of acronyms, signs, and gestures engraved on the windows of tramcars was related to the tacit battle between the taggers and the Berlin transit company (BVG) from 2008 to 2010 – when, after a number of fruitless attempts to protect the windows, BVG had a tinted film imprinted with the motif of the Brandenburg Gate placed over them, discouraging the taggers. As she photographed, Auerbacher was challenged a number of times by tram passengers (“You didn’t do that, why are you interested in it?,” “You don’t have the right to take pictures of that!,” and so on), but she leaves to barroom philosophers and political leaders the indignation and the accusations of vandalism along with the arguments about visual pollution and the costs of cleaning.

Although one might not take seriously a historical reference to the Vandals, it’s worth asking, Which empire do the taggers threaten? Their invisible and intangible community doesn’t demand anything explicit. We know only that tags are sometimes linked to marking territories during gang wars. If the taggers are defying a particular power, in the context of a Berlin marked by twenty years of intensive architectural and urban reconstruction, one might think that it is the power of design. The effects of design – which, one might say, is both integral and total today, pushing ever further a type of illusion of transparency and fluidity – can be seen when an urban zone is completely programmed and planned over a very short time. Design expands the windowed surfaces of each new model of subway car, bus, or tramcar proportionally, it seems, to the expansion of urban spaces reserved for advertising. Through the window-screen of a tramcar, design grows by a forceful kinetics that completes its idealization. Diluting the effectiveness of the window- screens by etching into their very fabric a collective and informal framework – informal because collective – resulting from a territorial struggle no doubt means resisting the obtuse violence of the simulacrum that blankets the experience of the city today. In this sense, Scratches retains the trace of one of its “tragic conflicts,” before which the artist, as Wolf said, must be “seized” and “overpowered.”

The dimensions of the twenty-five “photographic paintings” in the exhibition match those of a Berlin tramcar window (89 x 114 cm). Each wall of the gallery was painted with a colour from Berlin’s urban space: the yellow of the tramway, the red of the monorail, the blue of the signage, and so on. On these colourful walls, the “paintings” formed broken, rhythmic lines at three heights: those of a sitting passenger, a standing passenger, and a passerby. These choices of view made it possible to keep at an equal distance another transparency, that of the document, and the process of artialization through which reminiscences of action painting were sometimes superimposed over the artist’s gaze when she photographed. In this tension, the complex overlappings of planes and signs presented by the “paintings” within this installation gave viewers the sense of experiencing a diffracted perception of the city from the point of view of a collective subjectivity.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Taggers also use hydrofluoric acid, which etches the surface of glass. To judge by Auerbacher’s photographs, this technique isn’t widely used in Berlin. The extreme harm that it can cause to the human body has been the subject of lively exchanges in taggers’ discussion forums.

Visual artist Dominique Auerbacher uses various media in her work by articulating photographic images with text, video, painting, and sound. Born in Strasbourg, she currently lives and works in France and Germany. She is a professor at the École supérieure des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg. She has had exhibitions in various museums and artist-run centres, including ARC (contemporary section of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Casino Luxembourg, Kunstraum Innsbruck and Kunsthalle Hamburg. She has also participated in numerous public art commissions in France and Italy. Scratches will be on view again at the Urbi & Orbi Biennale in Sedan, France, from 1–30 June 2013.

Emmanuel Hermange is an art critic and a professor of art history at the École supérieure d’art et design de Grenoble-Valence. His publications concern the relations between photography and language in the nineteenth century, as well as the uses of photography in contemporary art, focusing particularly on issues raised by representations of the city and of labour.