[Fall 2013]

Maison de la culture Frontenac

29 January to 3 March 2013

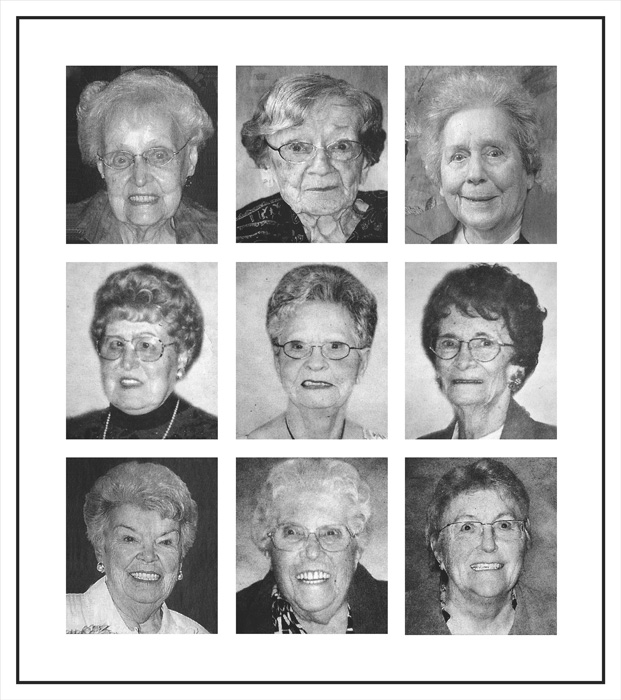

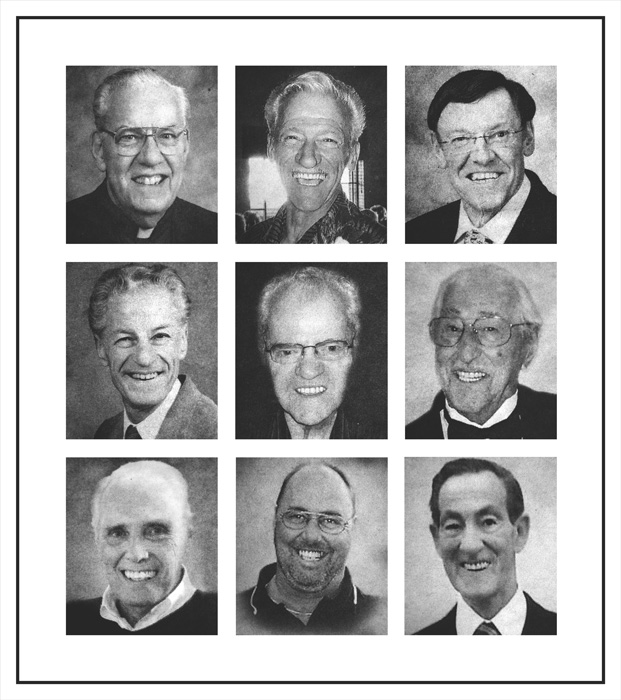

Obituaries, I am told, become a part of everyday life once you reach a certain age. At one point, these public announcements of death made in local newspapers on a daily or weekly basis take on more significance as you begin to recognize, either literally or figuratively, the names and faces of those who have died. Regularly reading obituaries is a way to both defy and ease oneself into death. Alain Pratte’s recent exhibition at the Maison de la culture Frontenac took the photographic material in obituaries as a starting point. Titled Des morts exemplaires, the show consisted of more than fifty large-format prints, each combining nine closely cropped portraits culled and rephotographed by Pratte from obituaries published primarily in Le Journal de Montréal, La Presse, and Le Journal de Québec. The uniformity of the artist’s chosen mode of display was matched by an equally carefully elaborated organizational logic: a typology based on gender, physiognomy, and demeanour that only emerged after some contemplation.

Each of the prints unites nine individuals, all of the same sex, and was shown as part of a group of four, five, or six, also organized by sex. Figuring out which characteristic ad brought a given set of faces together became a kind of game: some, such as men in police uniforms and women wearing extravagant glasses, were obvious, whereas others, such as men with strange noses and women with dumbfounded gazes, were determined subjectively. Many of these organizational features were downright comical (one group, for example, presented men apparently possessed by the devil), prompting one to wonder why on earth these people’s families felt it was a good idea to have their presumed loved ones remembered by such bizarrely unflattering portraits.

Such is the question that Pratte asked in the short text introducing the exhibition, in which he pondered the motives behind choosing to have these portraits stand as the final statement of a person’s existence. Amassing this material is a process that the artist initiated in 2008, when he noticed, as he read the paper each morning at his local coffee shop, that the dead were frequently shown laughing. Since 2009, when he began to collect the images more systematically, he has built an extensive portrait gallery, which, he says, he has classified according to his own prejudices.

When Pratte talks about the ongoing project, there is little trace of sadness or overt paying of homage. His way of typologizing these figures undoubtedly emphasizes their weirdness and humorousness; it is as though we are being encouraged to laugh in the face of death. It is significant that those whose derision has been sanctioned are easy targets: elderly, white males and females form the bulk of the corpus. The exhibition included no portraits of visible minorities, an absence that is explained by the demographics of the selected newspapers’ readerships, and Pratte deliberately left out images of babies and of mentally challenged individuals. Perhaps standing in for generic parent figures, these elderly, white men and women can be seen as emblems of a waning authority – and a waning society.

Pratte makes connections between this project and his other found-photograph works – for instance, the 2003 video À rebours, which is composed from a collection of unidentified negatives purchased from a curio shop. Here too, vernacular photographs deemed of little value have been salvaged and given new meaning. Des morts exemplaires also has commonalities with other, less likely of Pratte’s works – for example, Chiens trouvés, a series of portraits of dogs tied up outdoors produced between 1999 and 2004, and the 2005 series Dans le sac, in which the artist captures discarded plastic bags littering the streets. In both of these cases, he manages to bring out the subtle idiosyncrasies of his subjects and imbue them with personality. He appears to look upon such animate and inanimate objects with a great deal of empathy, as thoughhe somehow identifies with those who have been left out in the cold.

Similarly, the portraits of the dead assembled in Des morts exemplaires invite us to cast a tender gaze on the small eccentricities of ordinary people. Although they function within a memorial device, the images that appear in obituaries are ephemeral; only those who knew their subjects can claim them as photographic cenotaphs. By gathering these nameless faces together in perpetuity, Pratte offers an opportunity to remember that people are indeed strange, and that this, in the end, is the heart of humanity.

Zoë Tousignant is a PhD student in art history at Concordia University. She holds a master’s degree in museum studies from the University of Leeds, U.K. Her doctoral research concerns the emergence of photographic modernism in Canadian illustrated magazines between 1925 and 1945.