[Fall 2013]

If there is one category that seems to have escaped the crisis in the book-publishing sector engendered by the rise of digital publishing, it is photobooks, which are currently appearing at such a rate that it is legitimate to think they will eventually supplant exhibitions as the main means of dissemination of photography and, especially, photographic creativity. Easily accessible and available in a variety of forms, photobooks have opened a breach through which photography has escaped its traditional exhibition venues. Existing beyond the margins of galleries, museums, and magazines, photobooks are seen by a growing number of artists and devotees as a distinct field in the discipline, an “autonomous art form,”1 with its own institutions, publics, and communities of interest.

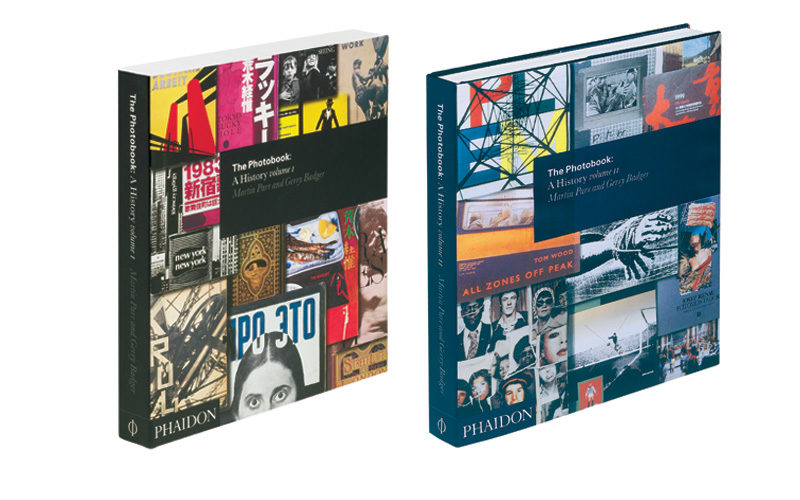

The photobook began its journey to autonomy at the turn of the twenty-first century, when the first reference books on the subject came out,2 and it was greatly helped along by the publication, in 2004 and 2006, of the two-volume The Photobook: A History.3 Drawing on the undeniable expertise of the books’ editors – photographer Martin Parr and critic Gerry Badger – this work inventories photobooks that have made remarkable contributions to this parallel history of photography, from William Henry Fox Talbot’s Pencil of Nature to Joan Fontcuberta’s Fauna and books by Ed Ruscha and Hans-Peter Feldmann. Providing the subject of the photobook with a solid enough historical basis to found a new field of research, the international panorama offered by Parr and Badger has opened the way to other authors who address the question of national or stylistic point of view.4 Although such studies are justified by the inherent interest in the subject, their proliferation attests mainly to the need felt by researchers to draw on history to legitimize the photobook as a contemporary art form.

This enterprise of legitimization, which is not unrelated to the phenomenal inflation in the prices on online auction sites of works with a historical stamp of approval, has resulted in the institution of an organized market, like that for photographic prints,5 based on rarity, and this has led to aggressive speculation.6 Just a few years ago, photobooks were valued only by an inner circle of knowledgeable collectors; now, specialized institutions play an essential role in this new market7 by helping to spread connoisseurship, constantly updating the supply and demand of new titles, and increasing the number of consumers – not to mention speculators.

The historical, economic, and sociological implications linked to the rise of the photobook, though interesting, are simply indications of an even more exciting reality, which is the raison d’être for this type of publication: their basis in creativity. The primary interest in every photobook, we can hope, is not its value as a tax shelter but its capacity to take advantage of the intrinsic characteristics of the book form to raise a body of photographic work to the rank of artwork. Although the photobook is recognized as an “autonomous art form,” it is appropriate to ask what exactly this art form is and whether there is a canon that, notwithstanding the diversity of books, would provide a single, encompassing definition. Rather than seeking an essentialist, and thus disembodied, answer to this question, it seems preferable to turn our attention to an art practice exemplary of the current issues underlying the production of photobooks because it is completely justified by such production: that of American photographer John Gossage.

Within the rapidly expanding world of the photobook, Gossage is a recognized authority. Since publication by Aperture in 1985 of his book The Pond, which has been widely seen and appreciated for having considerably raised the standards of the genre, Gossage’s reputation has been consolidated through projects designed expressly for presentation in books rather than exhibitions.8 Parr and Badger regarded him to highly that they asked him to define a series of criteria for the photobook for The Photobook: A History: “Firstly, it should contain great work. Secondly, it should make that work function as a concise world into the book itself. Thirdly, it should have a design that complements what is being dealt with. And finally, it should deal with content that sustains an ongoing interest. ”9 Although, as Parr and Badger admit,10 Gossage’s criteria do not describe all photograph books, they seem ample for an understanding of the exemplary nature and relevance of Gossage’s approach. Already at work in The Pond,11 these precepts seem to be taken to the extreme in the many books recently published by Gossage.12 These projects, without exception, count first and foremost on the artistic interest of their respective photographic corpuses. In his distinctive style, Gossage uses certain strategies first seen in The Pond, which aim to highlight the banality and enigmatic nature of the subjects photographed, such as shallow depth of field generating a bokeh that creates a dialogue among the different planes of the image, framings that are more evocative than descriptive, and subtle contrasts that unify the representation. In some of these works, Gossage trades his usual language of black and white for that of colour – for which he ventures for the first time into digital photography – and yet never undermines the coherence of his visual signature.

Gossage assigns a specific position to each image within groupings rigorously conceptualized as systems. Although he supplies some keys to understanding these groupings by slipping textual citations, often obscure and laconic, into his books, he does not give any further explanation of the principle behind the logic of these groupings. It is thanks to an accumulation of images that the reader gradually unravels the intrigue – and the enigma – of his books. The cohesion. of the groupings is reinforced by graphic elements that help to make the reader’s experience of the books more dynamic. Each aspect of the books’ manufacture reflects this, from format to paper, to binding type to cover.

Finally, the ongoing interest that Gossage’s books aspire to generate resides in their capacity to universalize the relatively personal corpuses that they present. Gossage’s photographs, which seem to be the fruit of multiple wanderings, usually appear to be linked to his private relationship with the world, and yet they also bring to light political, economic, sociological, and anthropological lineaments. Never trying to mask the particular condition of their producer, but instead highlighting it with anecdotal references drawn from his life, the corpuses in Gossage’s books are inscribed in an infinitely broader historical perspective. By mobilizing the resources of photographic narration, these books testify, in this sense, to the historicity of the present time.

Although further examination of Gossage’s recent publications would no doubt offer a more detailed illustration of the implications of his series of criteria for the photobook, it is possible to propose that his acknowledged expertise tends to position his approach as an essential model in this particular publishing field. Evidence of this can be found in the practices of a number of artists who, following in Gossage’s wake but without necessarily excluding the support of an exhibition, favour the book form for display of their work. Some of these artists are Ron Jude, J Carrier, Christian Patterson, Alec Soth, Rob Hornstra, JH Engström, Böhm/Kobayashi (Katja Stuke and Oliver Sieber), Takashi Homma, David Alan Harvey, KK+TF (Klara Källström and Thobias Fäldt), and Cristina de Middel. Paying due homage to Gossage, as well as to Moriyama, Petersen, Graham, and Parr, these contemporary practices have in common a desire to break with the stale models of the monograph and the catalogue to envisage, instead, the book and all of its variations as a perfectly legitimate “autonomous art form.”

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Horacio Fernandez, Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print, 1919-1939 (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1999); Andrew Roth, The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century (New York: PPP Editions and Roth Horowitz LLC, 2001).

3 Martin Parr and Gerry Badger (eds.), The Photobook: A History, vols. 1 and 2 (London: Phaidon, 2004, 2006).

4 Ryuichi Kaneko and Ivan Vartarian (eds.), Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ‘70s (New York: Aperture, 2009); Peter Pfrunder (ed.), Swiss Photobooks from 1927 to the Present: A Different History of Photography (Lakewood, NJ: Prestel, 2011); Horacio Fernandez, The Latin American Photobook (New York: Aperture, 2011); Frits Gierstberg and Rik Suermondt (eds.), The Dutch Photobook: A Thematic Selection from 1945 Onwards (New York: Aperture, 2012); Darius Himes and Larissa Leclair (eds.), A Survey of Documentary Styles in Early 21st Century Photobooks (self-published [Blurb], 2012).

5 Nathalie Moureau and Dominique Sagot-Duvaurout, “La construction du marché des tirages photographiques,” Études photographiques, no. 22 (2008), http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/index1005.html.

6 As shown in an intentionally caricatured, but very effective, book self-published by the artist Andreas Schmidt, featuring screen captures from auction sites and showing entries for each of the photograph books mentioned in the second volume of Parr and Badger’s work. See Andreas Schmidt, The Cost of Photobooks: A History Volume II (self-published [Blurb]).

7 Notably the Fotobookfestival in Kassel, Germany, and The Photobook Review, a supplement of the magazine Aperture devoted to news in the photobook field.

8 John Gossage, The Pond (New York: Aperture, 1985, republished in 2010). Aside from The Pond, other significant books published by Gossage before 2010 include Stadt des Schwarz: Eighteen Photographs of Berlin (Rockville, MD: Loosestrife Editions, 1987); There and Gone: One Hundred and Twenty-Four Photographs (Portland, OR: Nazraeli Press, 1997): Empire (Portland, OR: Nazraeli Press, 2000), and Berlin in the Time of the Wall (Rockville, MD: Loosestrife Editions, 2004).

9 Parr and Badger, Livre de photographies, quoted by Gerry Badger in “Genesis of a Photobook,” in John Gossage, The Pond, (New York: Aperture, 2010), n.p.

10 Ibid.

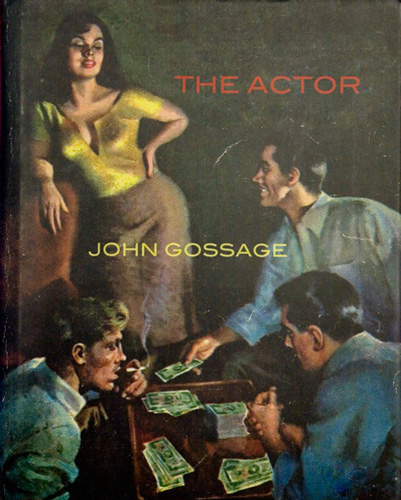

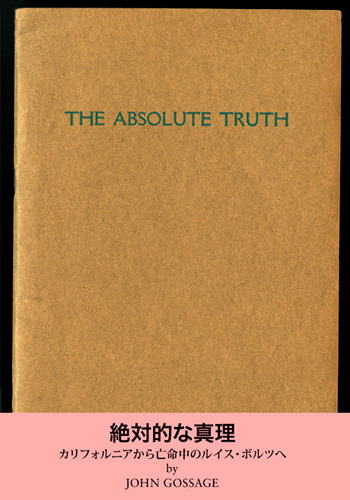

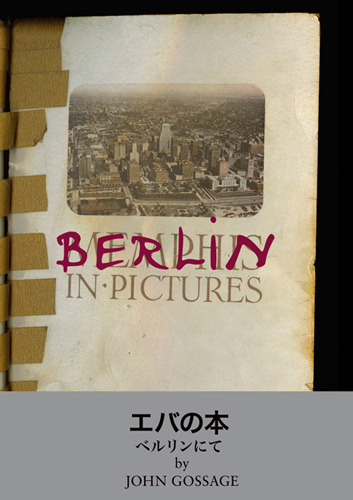

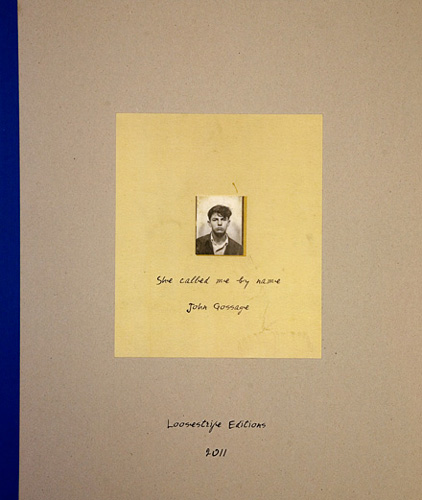

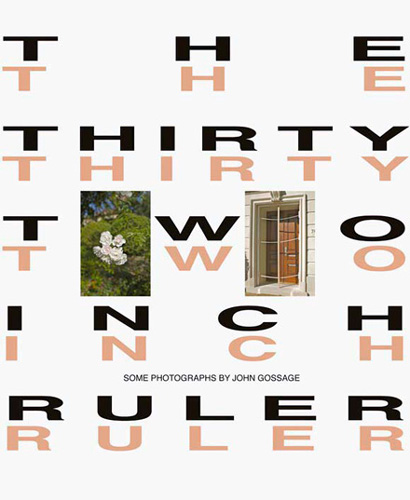

11 As mentioned in the essay that Gerry Badger wrote for the 2010 republication of this book; see Badger, “Genesis of a Photobook,” 12 Aside from his contributions to edited books, Gossage has published at least eight new projects since 2010: , including Here (Rochester, MN: Rochester Art Center, 2010); The Thirty-Two Inch Ruler/Map of Babylon (Göttingen: Steidl, 2010); She Called Me by Name (Rockville, MD: Loosestrife Editions, 2011); The Absolute Truth (Kanagawa: Super Labo, 2011); Eva’s Book/Berlin in Pictures (Kanagawa: Super Labo, 012); The Code (East Hampton, NY: Harper’s Books, 2012); The Actor (Rockville, MD: Loosestrife Editions, 2012); and Looking Up Ben James – A Fable (Göttingen: Steidl, forthcoming in 2013).

Alexis Desgagnés lives and works in Quebec City. His research dialectically addresses photography theory and practice. A regular contributor of articles to Ciel variable, his photographic work has been exhibited at L’OEil de poisson (Quebec City) and Regart (Lévis), as well as in various magazines. Desgagnés is a lecturer at the Université de Montréal and Université Laval, as well as artistic director of VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie.