[Fall 2013]

by Christelle Proulx

The “nine eyes” in Jon Rafman’s project refer to the photographic device mounted on the roofs of Google cars. These cars have been travelling the world’s roads since 2007, equipped with cameras with nine lenses, taking pictures of streets – images automatically in street view – for use with the Google Maps tool. This tool offers Web surfers an opportunity to “explore the world at street level,”1 by enabling them to see the places that maps represent abstractly. The works in the Nine Eyes series come from screen captures taken as Rafman spent long hours “wandering” on streets produced by the Google Street View images in order to find and appropriate images that “deserved” a photograph. Since 2009, he has extracted pieces of this Web continuum to make individual photographs that have captured amusing and, sometimes, disturbing situations, or grandiose and unsuspected landscapes. Presented on a Tumblr blog platform (9-eyes.com) and exhibited in a gallery once printed in large format, Rafman’s surprising images have drawn the attention of a number of well-known galleries and magazines.

After exploring a virtual online world in his project Kool Aid Man in Second Life (2008),2 in Nine Eyes Rafman examines the transposition of physical public space to the Web. Street View is both a vast online territory and a device that gives the impression of visiting different places through photographic images. The geographic sites seem to come to life on a Web site, thus producing a parallel between the two types of sites. Rafman takes advantage of Google’s incredible documentation of the world to uncover what, in his view, among everything that has been captured automatically, makes a photograph, returns a bit of importance to the individual in the taking of the picture. By moving deep into the fixed image and despite the constraints of previously captured source images, he can choose the frame of his photographs as he would with his camera. Screen capture is the cyberphotographer’s method of selection, and he chooses to leave the traces of the interface intact, such as, for example, the directional compass that adorns the corner of each image. Using a keystroke command, he re-cords what appears on the screen. It is a task of collection that he delivers to us by sampling this gigantic assemblage of images addressed to a public who consults them only for their utilitarian value.

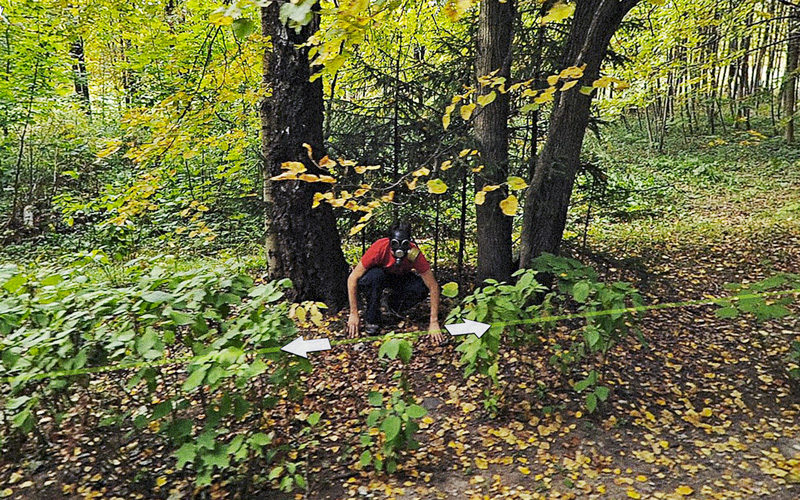

By isolating these images, Rafman produces a parallel archive that makes visible and extends the life of snapshots buried under the immense mass of Street View’s visual materials. In effect, Nine Eyes often captures ephemeral fragments since images in Street View are likely to disappear in favour of new ones that better portray a particular place. The temporality of the image is interchangeable with the legibility and currency of the place’s representations; shots of it that have human or technical “anomalies” will eventually be replaced by ones that are more “informational.” In fact, this is what often fascinated Rafman in his selections that feature human beings: pedestrians, accidents, prostitutes, or arrests captured by the multi-lens camera involuntarily, mechanically, and usually by mistake. The spaces photographed for utilitarian purposes are inevitably inhabited, and the artist chooses images that are likely to be considered anomalies in Street View. Although these are images of a world in which it is always daytime and the weather is always good,3 the conditions of the series testify to the public space and what is uncontrollable about it. Nine Eyes sometimes involves images of activities that should not have been photographed and illustrates how acting in the pubic space or on the “public way” inherently bears the potential of being inappropriate, or even illegal.4

By selecting images of scenes that a traditional photographer probably wouldn’t have been able to capture, Rafman foregrounds the intrusive nature of this mode of systematic documentation, which considers everything visible on the street to be public.

The split image of an old man in 8 rue Valette, Pompertuzat, France shows a pedestrian and a technical anomaly caused by the mechanism for reassembling the images and re-creating the man’s movement. It illustrates how, in Street View, individual instants in real geographic space are stitched together into a fixed ensemble that Rafman fragments once again. The automated image system’s deficient splices and captures punctuate the series. Often corrected after a certain time in the matrix, they both are evidence of the imperfection of the recording device and present an opportunity for Rafman to draw from this artistic blur images that become artworks once isolated. Then, by titling his works with the postal addresses assigned to the images by Google, he reminds us that these are geotagged images that inscribe real space in cyberspace.

Street View presents us with a spatial conception of what is public, thus taking into account the space of the street and not what is happening in it, and with little regard for whether such activity is in the private sphere. This is a public space in which individual identity should not prevail – even legally – which has led to the design of algorithms to systematically blur faces and licence plates. By selecting images of scenes that a traditional photographer probably wouldn’t have been able to capture, Rafman foregrounds the intrusive nature of this mode of systematic documentation, which considers everything visible on the street to be public. This is a type of surveillance that records the space without apparent intention to control. Nevertheless, this supposed neutrality provides a rationale for disturbing captures and allows cyberflâneurs to explore all sorts of places in voyeur mode.

Reflecting the tradition of street photography, the images extracted from Street View remind us how the notion of the public space is linked to that of the public way, the street. Street View gives the impression of documenting a good part of the globe, and yet it’s not exactly the whole world that is revealed to us in these photographs, but only the point of view of streets.5 As Vito Acconci wrote in 1990, in the electronic era the public space is defined no longer as places such as parks and squares, but as roads on which we circulate.6 The Street View point of view reiterates this conception and tends to evoke the street as shared democratic space and the car as symbol of individual freedom, as well as reflecting the Google philosophy, which aspires to democratize knowledge by making all information in the world accessible. The development of the Internet network, following the road network, constantly increases the mobility of images, shrinking spatiotemporal distances, just as photography produces a similar shrinking. Nine Eyes is the photo album of the virtual voyage of a cybertourist who explores territories in images, between physical reality and fictive space.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 http://maps.google.ca/intl/fr/help/maps/streetview/

2 http://koolaidmaninsecond life.com

3 Google takes account of the sun’s position and the weather forecast when it plans its cars’ itineraries.

4 Andreas Boeckmann, “Public Spheres and Network Interfaces,” Cybercities Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004), p. 380.

5 Street View pans are now captured on snowmobiles and on foot.

6 Vito Acconci, “Public Space in a Private Time,” Critical Inquiry, vol.16, no. 4 (1990): 911.

Christelle Proulx is a master’s student in art history at the Université de Montréal. Her research topics are photography, the Web, and new technologies.