[Winter 2014]

First in the sightline for those entering Googleheim, a group show curated by Horea Avram at Interaccess in Toronto:

a wireless mouse on a plinth. It might have been a monument to audience engagement – a succinct overture to a show invested in dialogue between the museum’s interest in artefacts and the Internet’s provision of access. It wasn’t that, though; interaction was not particularly celebrated here. The mouse was a red herring.

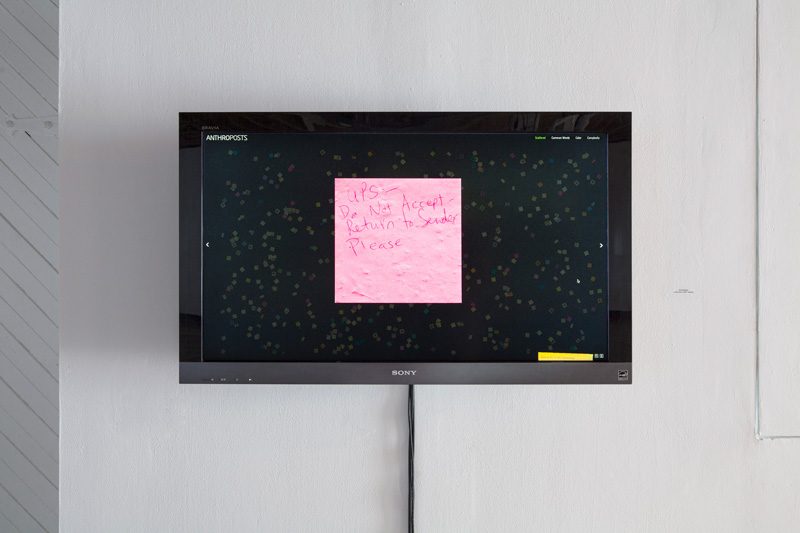

The interactive wings of the art on view were often clipped. Some of the clipping was curatorial: exhibition-goers could use the mouse to peruse an archive of Noah Pedrini’s found Post-it notes, but the project’s sound track (though discussed in the exhibition text) was not played. The gallery didn’t proffer the opportunity to click through the rooms of Stephane Degoutin and Marika Dermineur’s real-time architectural experiment, Googlehouse. The links displayed in Angie Waller’s Google Earth tour of allegedly boring places could not, in the space, be followed.

Both Maco Cadioli’s manipulation of Google Maps and Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead’s A Short Film on War thematized crowd-sourcing and public software, but they used video – a medium that comparatively neuters its audience – to do it. Viewers were immersed in Internet tropes and iconography but were denied the control over experience that denizens of Google have come to expect.

The Internet appeals to us as creatures who select and specify. Unhewn blocks of search bar beg for the refinement of our whittling keystrokes; images compel us to zoom in – and out – at will. So, at the level of contemporary reflex, it was jarring to be kept from clicking on, scrolling through, or typing into the interfaces that Googleheim presented.

Of course, mouselessness is far from paralysis; there are other, and less cursory, ways to engage. Perhaps Avram, with one foot in museological convention, wanted to remind us that interaction predates and exceeds the digital. In the analog visual arts, audience participation can be as simple as contributing attention; sometimes viewers’ eyes are needed to mix pigments, and sometimes their presence is required for a piece of performance or relational art. Now, as Googleheim and countless other projects attest, art and the Internet overlap – and how our orientations to each might also overlap is worth major thought.

We’re reminded that our orientations are structured by the fact that Google and Guggenheim are both, ultimately, brands – ones with extreme influence on our radical, intimate, and everyday experiences. Unfortunately, this point is not well drawn out by the show. Disappointingly, nor does Googleheim privilege the feature so vital to its twin muses’ success: compelling design. The seemingly arbitrary placement of the works on the walls of Interaccess was neither a stunning use of space nor particularly user-friendly.

What’s most unfortunate is that the works in Googleheim were missing more than can reasonably be supplemented

by viewer imaginations or curatorial positioning. Many made promising first steps, but seem to have stalled at the level of concept; even those that were not ongoing felt unrealized. Cadioli, for example, takes up the Borgesian notion of a map without territory. Leaving an overlay of Google Map icons, he has liquidated the land below into an eerie white void. It feels preliminary. Why clear this space; for what? Nothing rushes into its vacuum. And yet there is possibility: could Overdata help us conceive a map of Mars? Or might its whiteness figure the gallery landscape?

The Most Boring Place on Earth is similarly promising and similarly underdeveloped. Waller’s project spins around the world to hover above locations claimed by anonymous bloggers and commenters as the most boring. The topic is significant, and even crucial: as technology changes the ways we pay attention, the phenomenon of boredom becomes more interesting. But we don’t get even as close as Street View to the destinations that Waller sourced. Boredom is mapped but not really felt, or explored. Art should do more than code unusual applications for impressive software.

Software, after all, is quickly outdated. The newest works in the show are from 2010, which, in digital time, is eons ago. Snowden had not yet exploded today’s privacy paranoia; 3D printers had not laid such a shockingly easy path from image to object; Snapchat had yet to infiltrate, with its built-in ephemerality, a medium obsessed with traces.

What’s good about the art and conceit of Googleheim is relevant to all of these developments. I can imagine Overdata expanded to illuminate the significance of metadata. I can picture printing Googlehouse. I can wonder what museums might take from Snapchat. But my musings aren’t enough.

Heather White is a Toronto-based writer currently drawn to experimental intersections of fiction and criticism. She holds

a BA in contemporary studies and history from the University of King’s College, Halifax (2007), and an MA in philosophy and art from SUNY Stony Brook at Manhattan (2009), and she received a writing prize from the Canadian Art Foundation in 2012.