[Winter 2014]

I had the pleasure of being invited by Chuck Samuels, the director of Le Mois de la photo à Montréal, to join Paul Wombell, the curator of Le Mois de la photo 2013, at the screening of art video shorts and a presentation of Michael Snow’s La région centrale (1970) at La Cinémathèque québécoise. Of course, the general theme of this year’s edition, Drone: The Automated Image, explored the issue of the automation and autonomy of machines and instruments, but also, as Jacques Doyon’s interview with Wombell revealed, that of agency.

In these terms, it becomes possible to advance a critique of the “automated” image, but first we must come up with better definitions and ways to distinguish the machine from the instrument, the machinery from the instrumentation. If we read Doyon’s interview with Wombell in French and English, there is an obvious shift in meaning between the French appareil and its English translation as “instrument.” I have discussed elsewhere the translation issues around the term appareil, which I proposed to translate into English as “apparel,” to differentiate it from instrument and from dispositif, which is often translated as “apparatus.” 1 Here, I will go more directly to the heart of the question: how to distinguish between the machinery and the instrumentation of vision.

During the 2000s, Jean-Louis Déotte led the way in theorizing the notion of appareil.2 In his book L’art au temps des appareils, Pierre-Damien Huyghe writes of a “photographic condition of art”3 within which the (photographic) machine “invents correlatively, in the absence of appropriate savoir-faire, a subject and an object [and] develops a possible state for this correlation.”4 The machine is conceived of here as something that causes to appear, that enables the eye to see independently, or that reveals what the naked eye cannot see. Huyghe also states that machines evade all “instrumentalization.” The theoretician of dance Véronique Fabbri distinguishes the machine, which “arranges the material and renders it available for its transformation or for being set in motion,” from the “instrument, tool, or apparatus, [which] have the common function of transforming a material, of submitting it to a form.”5 These distinctions, however, do not prevent Déotte and Fabbri from confusing the instrumentalization of nature and people, for purposes whose qualification arises from a moral, ethical, or political judgment, with instrumentalized action or play. In a perspective in which the machine allows for material to be arranged and rendered available, it is in fact more productive to think of the instrument as a means of interaction and play as much as a form of agency serving purposes that may, moreover, be beneficial or destructive.

Thus, the idea that networks and the Internet change the relations between private and public space may be thought of as an effect of machinery. The technologies, computers, and cameras that now crisscross the planet – all of this ambient machinery – make it possible to erase the border between private and public by making the private sphere a material that is available. They produce a “vision” that is not so much automated as machinic: machines reveal the private sphere and render it available in a hyper-accessible public sphere. Cheryl Sourkes’s works – Everybody’s Autobiography (2012), Facebook Albums (2010), and BRB (2010) – draw on such material from private life. But what about the instrument? In effect, the instrument poses the question of agency, but not only in the sense of use for a purpose. The notion of instrumental agency, studied by the philosopher of science Don Ihde,6 presents a phenomenology of body/subject oriented toward and within the world, and it is this orientation that constitutes its agency.

In science and in music, the instrument is a mediator between an intentionality of knowledge, or play, and the objective sought – an objective shaped by the use of instruments that are embodied in a relationship with the researcher’s, or instrumentalist’s body. Thus, instrumental mediation is coupled with human mediation and produces an instrumentalized body/subject that is a “being of relations,” as Gilbert Simondon calls it to emphasize the dynamic of relations rather than the fixing of the material by forms, as opposed to philosophical hylomorphism. Simondon states, “A wide gap exists, in fact, between living beings and the machine . . . that comes from the fact that the living being needs information, whereas the machine uses essentially forms. . . . The living being transforms information into forms, the a posteriori into the a priori; but this a priori is always oriented toward receiving information to interpret.”7

This is true also of the digital instrument – the instrument built to process information – which is neither immersive nor ambient, but maintains an objectification that establishes both a rupture and a mediation between the instrumentalist and the object (music or natural data), creating an instrumental interaction. The drone is one of the instruments that involves such a distancing: a soldier sits before a screen operating a joystick, as if playing a video game. This remote-controlled instrument is based on the global telecommunications machinery that transmits images and data in real time and makes space and time into material rendered available to an instrument of war.

The technologies, computers, and cameras that now crisscross the planet – all of this ambient machinery – make it possible to erase the border between private and public by making the private sphere a material that is available.

* * *

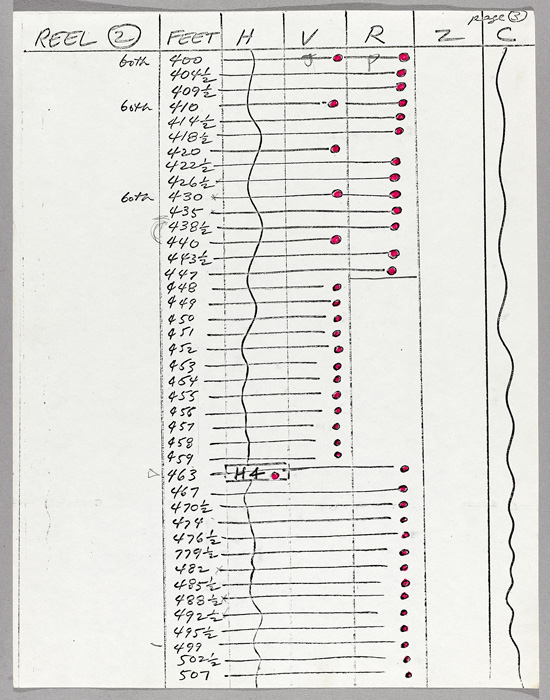

Agency and control are also at the core of the instrumental relations operating in an artwork such as Michael Snow’s La région centrale. This work8 shows how fine is the line that sometimes separates the machinic work from the instrumental work. The film was shot with a device with a robotized arm carrying a camera that could turn in all directions. As a simple recording of what the machine made it possible to film, La région centrale could be considered the result of an instrumentalized performance.

Snow’s original project also involved a dimension of instrumental play. Pierre Abbeloos, the builder of the device, suggested and designed a way to use audio tracks to control the camera’s movements on the mechanical arm. Electronic beeps at different speeds and timbres were recorded for this purpose; however, the artist and the engineer did not have the time to develop and use this system.

The sound was therefore produced after the images were edited. Later, Snow remodelled the sound using a small oscillator-synthesizer in the original logic of a score modulated by the image track and the final technical script.9 This approach to composition and execution of the sound component of the artwork is interesting as both “machinic art” and “instrumentalized art.” Conceived as issuing from the machine, the work influences the senses and perception by rendering the landscape available to a disembodied gaze; conceived as an instrument, the artist has composed it to be executed according to a program. So, is La région centrale the recording of an instrumentalized work for the cinema?

I will leave this last question unanswered. But in my view, the distinction between machine and instrument is crucial for articulating our now-technological relationship with the world and avoid the pitfalls of either a technophobic or a techno-utopian position. Whether this distinction is applied strictly in the art sphere or in more global spheres of life and culture, it allows us to address moral and political aspects by distinguishing levels of agency. Once technology engages, deploys, or arranges a material, that material then becomes prey for artists, scientists, and soldiers of all types.

2 See two volumes edited by J.-L. Déotte, Appareils et formes de la sensibilité (Paris: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques, 2005) and Le milieu des appareils (Paris: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques,2008); two books of which he was the author, L’époque des appareils (Brunelleschi, Machiavel, Descartes) (Paris: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques, 2001) and Qu’est-ce qu’un appareil ? Benjamin, Lyotard, Rancière (Paris: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques, 2007); and the book that he co-edited with M. Froger and S. Mariniello, Appareil et intermédialité (Paris and Montréal: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques, 2007).

3 P.-D. Huyghe (ed.), L’art au temps des appareils (Paris: L’Harmattan, coll. Esthétiques, 2005) (our translation).

4 Ibid., 25 (author’s translation; see Gagnon, Apparatus, Instrument”).

5 V. Fabbri, “De la structure au rythme. L’appareillage des corps dans la danse,” in Huygue, L’art au temps des appareils, p. 96 (our translation).

6 D. Ihde, Instrumental Realism: The Interface between Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Technology (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991).

7 G. Simondon, Du mode d’existence des objets techniques (Paris: Aubier, 1958), 137 (our translation).

8 Presented at the Cinémathèque québécoise on 17 September 2013 as part of Le Mois de la photo à Montréal.

9 Jean Gagnon, Digital Snow [DVD-ROM] (Montreal: Fondation Daniel Langlois and Paris: Éditions du Centre Georges-Pompidou, 2002); Anarchive 2, www.fondation-langlois.org/digital-snow.

Jean Gagnon is the director of collections at the Cinémathèque québécoise à Montréal. After earning a BA in fine arts, with a major in film production and film studies, he worked at the Canada Council for the Arts for three years before becoming associate curator of media arts at the National Gallery for Canada, a position he held for seven years; he then was executive director of the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology for ten years. He has taught in a number of Canadian universities and acted as a consultant for cultural organizations. Recently, he undertook doctoral studies in art studies and practices at the Université du Québec à Montréal.