[Winter 2014]

By Isa Tousignant

Walk around in early winter and you may just spot a dash of colour peeking through from under the first coats of snow that blanket the front gardens. That’s a carnation. Long after the peonies, lilies, and daffodils have gone, this sturdy flower still shines its bright hues, in defiance of the season of death. It’s fitting that it is one of the flowers most commonly used in funeral wreaths, but it’s also a mainstay in Mother’s Day bouquets and prom corsages. Its eternal will and refusal to wilt make it the ideal marker for our rites of passage.

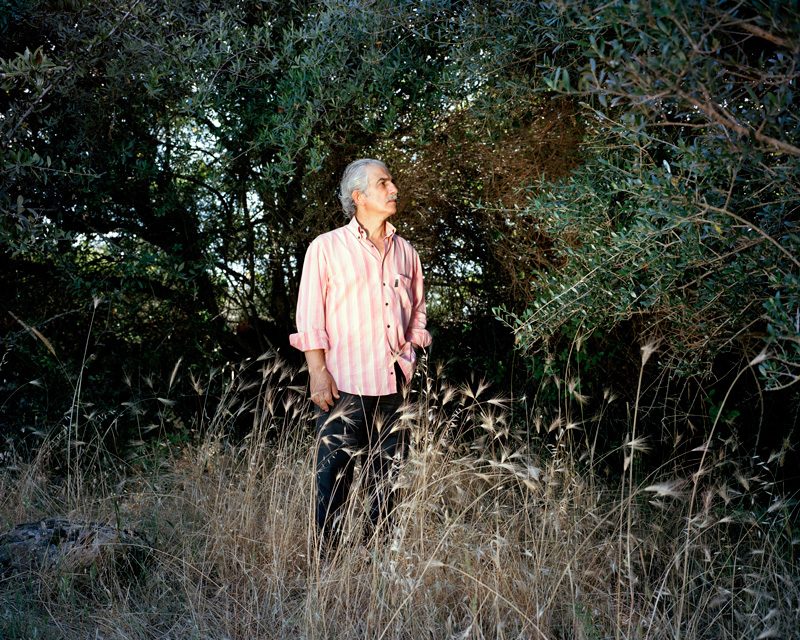

When Marisa Portolese came across a patch of pink carnations in Italy, while she was shooting her autobiographical project Antonia’s Garden, she couldn’t help but capture it, because the light was right, the palette was soft, and it was an irresistible image. But she had no idea that it would ever be a part of the profoundly personal body of work she was in the midst of producing. Over the course of the four years that went into Antonia’s Garden, though, as she made images, sifted through images, discarded images, and reconsidered images until she ended up with the ultimate selection of thirty-five, she also did research. She read that pink carnations are said to have first appeared when the Virgin Mary cried for Jesus as he carried the cross. The flowers blossomed where her tears had fallen and became a symbol for a mother’s undying devotion. As a lapsed Roman Catholic working on a project that has matrilineal relationships at its core, that symbolism could not have been more apt for Portolese. The image was selected and became Carnations: A Mother’s Tears, one of the most poetically potent photographs in this watershed project.

Portolese began this body of work in 2007, right after exhibiting Breathless at Galerie Trois Points in Montreal. That series of eight photographs was the first that combined isolated landscape and still-life images into her practice, which had up to then had consisted exclusively of portraits. Nature had always been an integral part of her work, but it had played the role of background up to then. With Breathless, the emotionally powerful portraits of women (the artist’s specialty) were buttressed by images of spaces and things that were devoid of people – a night sky, a vase filled with flowers. And the portraits’ power was enhanced. Portolese, a born storyteller, has always mined the narrative power of photography. Through juxtaposition, the addition of landscape and still lifes enhanced the tale, like clues in a mystery, or memory flashes in a film, or panels in a graphic novel.

. . . landscape and still life . . . themselves became portraits of someone or of an emotion or of a situation . . . it’s not important who that person is in real life.

Antonia’s Garden is the culmination of that approach. Created for not only an exhibition but a monograph, the project was conceived by the artist as a story that would exist in print, to be held in its viewer’s hand. And though their order has been known to change and parts of the series have been displayed in isolation within group exhibitions, the project is in its best, truest form as a whole, so that each image can dialogue with the others. It was the first time that Portolese had made such a large and time-consuming project; it was also the first time that she had told an autobiographical story. And whereas, up to that point, Portolese had exploded the conception of specificity when it comes to portraiture (her images weren’t homages to the particular people portrayed but iconographic representations, in which her subjects were players in a problematic that she was working out), this project required a different approach. For Antonia’s Garden, Portolese purposely created a divide between the personal and the universal. The result is a story, written like a play, with acts and scenes, that takes a heart-wrenching moment of family trauma and makes it beautiful, meaningful, and redemptive.

We discussed the project in her Montreal home.

What were your first steps into Antonia’s Garden?

In 2007 my grandmother, whose name is Antonia, became ill. We were called and told she might not have very much longer to live, so my mother and I went to Italy. I brought my camera. I wondered if it was weird, when something so dark was happening, but I brought it anyway.

When we got there things weren’t as bad as they had seemed, but she was bedridden. So we spent time with her, and I started photographing. I became very inspired by what was happening around me: the family dynamic, the relationship between my mother and her mother.

What was some of the baggage behind those family dynamics?

The historical context is that when my mother was seven, she was living in Sardinia with her family, and her aunt, who lived in Calabria, in the southern part of Italy, became very ill. My mother’s parents sent her to live with that aunt. She left her family home and never went back – she was to meet my father in Calabria, years later of course, and from there she moved to Canada. My mother suffered immensely from abandonment.

That event was never something that was openly discussed. But in 2007, my grandmother started talking about it. She said she regretted it, and she wanted to be forgiven. She revealed the reason that she’d done it: this aunt was alone, she’d been abandoned by her husband. What was happening around me was incredibly emotional, so I became inspired. It was very cathartic.

Was it cathartic for you as an artist, or more on a personal level?

Both, because as an artist, I was also learning how to put images together differently. In previous bodies of work the theme was very clear. I’ve worked a lot with women, and portraiture is the basis of my practice. My approach was always much more pragmatic: I want to talk about this, so I find ways to capture it through different portraits.

With this project, I felt free to put images together in a way I hadn’t done before. I knew that it had to work not only in a gallery, but in a book, and that the story had to be clear – not that I had to give all the answers away, but it had to function. There was a level of experimentation with how images would speak to each other, working with diptychs, working with triptychs, working with different chapters within the big picture.

With Breathless I had started to get more comfortable with the introduction of landscape and still life, and how they themselves became portraits of someone or of an emotion or of a situation. For me, despite the fact that they’re all related to me and somehow affected by the story, it’s not important who that person is in real life. All the protagonists are symbols. This could be my mother and her mother, but it could also be my mother and me. They’re stand-ins for that universal issue. By the same token, an image like Carnations: A Mother’s Tears is just flowers, but it could mean so many things.

What was the meaning of the garden for you?

It was a metaphor for the family: it’s something you cultivate, something you create, the results are a product of who you are. I thought it was important that it was really Antonia’s garden because this all revolved around her house and her life and her story and her decisions. Did your grandmother live throughout those three years of you working on this? She lived though the entire project, so I photographed her until the end. I published the book in 2012, and she died in February 2013. She died having seen all the images.

What was the project’s aftermath?

I can say this only now, after time has passed, but I was kind of mourning my grandmother before it happened.I knew the end was near, and when she died, I wasn’t as sad as I thought I would be, and I think it’s because I had been processing it for the last five years. When it happened it was like the end of a chapter. It happened in reality and within the work.

Marisa Portolese is of Italian origin but was born in Montreal, Quebec, where she currently lives and works. She is an associate professor in the Photography Program in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Concordia University. Her practice includes photography and video, as well as curatorial work for several institutions. After graduating with an MFA from Concordia University in 2001, she has produced many photographic projects that have received critical acclaim: Belle de Jour (2002), The Recognitions (2004-05), Breathless (2007), The Dandy Collection (2003-08), Imagined Paradise (2010), Pietà (2010) and Antonia’s Garden (2007-2011). A monograph of Antonia’s Garden was recently published by UMA-La Maison de l’image et la Photographie. Portolese is represented by Lilian Rodriguez (Canada) and Charles Guice Contemporary (USA). marisaportolese.com

Isa Tousignant is a contributing editor to the magazine Canadian Art, a blogger on the Montreal arts scene for akimbo.ca, and a freelance writer on culture, lifestyle, design, and travel. After working as a newspaper and magazine editor for over a decade, she recently left the land of cubicles to write her first book, about animals in contemporary art.