De la piscine aux verts

OPTICA, un centre d’art contemporain, Montréal

11 May to 15 June 2013

Richard Deschênes’s exhibition De la piscine aux verts (Optica, May to June, 2013) is composed of pared-down images – made entirely of cut-out and recombined press photographs – that shift among painting, collage, photography, and text. This visual and semiotic dynamic thwarts any attempt to definitely qualify them in a single category. In my view, however, these hybrid artworks can best be described as pensive images, to borrow Rancière’s terse formulation. Such an image generates a tension between intersecting visual registers and thus mobilizes thought from within its operative constitution. To better understand this generative tension, I shall briefly examine how the artist’s approach, informed primarily by painting, is extended and renewed through visual materials (press photographs) and a technique (collage) that are distinct from painting. Ultimately, though, I hope to make clear that these works are best understood as paintings, albeit paintings produced by other, impure means.

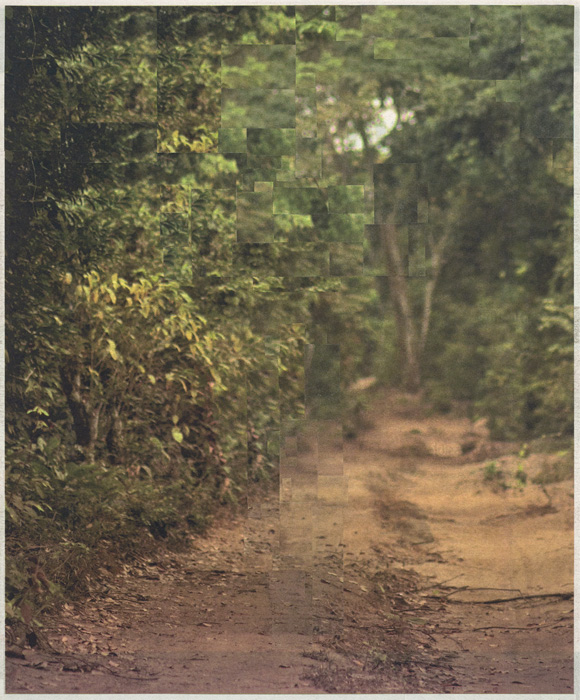

In Deschênes’s case, the mediated image exists as a presence in which it is not fixed but suspended in a state of unresolved tension between visual registers that compel the viewer to think with and through the image rather than about it; the mediated and reworked images are not as much formed as in-formation. Operating like a metaphysical surgeon, the artist makes incisions to subtract the central figure-subject from a photojournalistic picture, chosen after perusing a multitude of newspapers to find a background that is enticing not only aesthetically but also with regard to its title and the anticipated intervention. He then grafts and sutures elements from two or three identical copies of the chosen photograph to reconfigure and imagine a new ground to take the place of the ablated figure-subject. Although the recomposition effectively creates a visually credible ground so that the picture field is completely filled, it is in fact a pure fiction. For instance, in the work titled Girl Powers (War Witch) – Kim Nguyen, the vanished figure-subject is replaced by an array of variously sized rectangular and square cuttings pasted together to compose a subjectless forest landscape. However, the initial ablation process creates a void that can be filled only through the imagination, for the as-yet-unformed ground has no reference in the real and can be invented only via a creative process that is clearly informed by the idiom of painting (manual composition of visual forms, colours, and textures to create an abstract or figurative visual field). Note that in order to invent this pictorial space Deschênes is compelled to return to the original image, for in order to refill the void with verisimilitude he can be guided only by what remains of the photograph. In other words, to fashion the nonexistent space he cannot but work from what subsists of the pictorial real in the photograph: in order to accurately and convincingly invent what never was, the artist must remain faithful to what remains – a reality that pertains not to the picture’s representational or referential function (obliterated by the vanished figure) but to what is “really” present within it as an image.

Viewed as a completed picture, it is not the image of the forest that piques the gaze, but the fuzzy, punctured area in the centre, which is the lieu of the vanished figure and reconfigured ground, a patched-together field of scar marks that can be likened to the notion of the punctum introduced by Barthes. However, the punctum, “this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me . . . this wound, this prick, this mark by a pointed instrument” so thoroughly proliferates the picture that it becomes the studium (whereby Barthes designates a photograph’s scene or intentional subject). But, since the punctum/studium binary depends on the interplay of the two terms, the all-punctum image cancels both out. Instead, it is the pensive image, alluded to before, that characterizes the visual logic inherent in the exhibited series.

Even though the works are closest to painting, in both process and aesthetic effect, they are impure paintings in which the coexistence of various image registers and the title text generate a tension that traverses and binds all levels of what is made visible. A viewer who attentively reads these images is invited to activate the pensiveness inherent in the incessant transfer among these multiple registers. Such a reading invariably makes clear that these pictures are decidedly undecidable. As paintings, they include various genres, from figurative landscapes and urban studies to abstract painting, and resist classification within a single typology. But these hybrid, impure paintings are made up of residual photographic elements that, however modified and unmoored from their referential shackles, continue to inform their visuality.

And finally, there is the presence of the titles, which mobilize yet another level of semiotic interrelations. The titles (which are in fact the captions that accompanied the original photographs) are not extraneous adjuncts to the works, but an integral and operative part of them. A case in point is the title Jessica Zelinka of Calgary completes in the shot put portion of the heptathlon, which, though it linguistically evokes a picture, in this case refers to an image in which this word-picture is the object of the vanishing, of the subtracted studium. The title is hence also unmoored from its referential context, orphaned and left to itself to take on a quasi-poetic function within the image-text loop.

Interestingly, this title refers to a picture that at first glance appears to be a purely abstract green field painting, but that on closer inspection reveals the presence of newsprint text on the recto side of the semitransparent paper that is the support of all of the works – another level of impurity in which the support asserts its residual status as a media object despite the painterly manipulations.

With this series of works, Deschênes also asserts that, despite the many death knells announcing its imminent demise, painting can still devise novel ways to revitalize itself, expand, and reappear, albeit in an undecidable, pensive, and impure form.

Bernard Schütze is an independent art critic, curator, and translator. He regularly has articles published in various art magazines and has written numerous catalogue essays and monographs. He has been invited to speak at art-related events and universities in Canada and in Europe. He lives and works in Montreal.