By Alexis Desgagnés

I discovered Marcel Cognac by chance – a chance presented to those who know how to wait for it, to those who want to understand something about their culture and their country. When I came across a copy of his book Visages du Québec, published in 1964, with text by Jean-Charles Harvey, I didn’t yet know that Harvey, who died twelve years before I was born, was a child of the magnificent landscapes of the Charlevoix region (as my parents had been). Nor had I yet read his inflammatory Les demi-civilisés, of which I managed to save a copy – $2.95 at the Salvation Army – from the contemporary book-burning to which my society is succumbing. At the Colisée du livre de Québec, however, it was not Harvey’s reputation as a writer that guided my hand toward this copy of Visages du Québec. What caught my eye was the book’s magnificent cover, devoid of a title, featuring a black-and-white photograph of logs. A log-drive scene: my first contact with Marcel Cognac.1

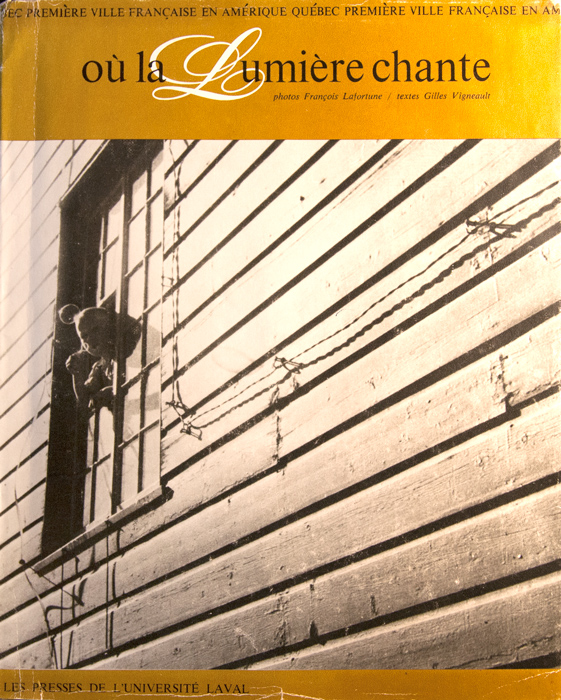

Although it is beautiful, the book isn’t enlightening. Leafing through it, one finds a photographic celebration of perpetual, timeworn stereotypes of Quebec culture. I won’t list those stereotypes here, as you may have already brooded over them to the point of being ashamed of them. As it recently occurred to me that this shame no longer inhabited me, I have come to consider this book one of the links in the chain of the as-yet-uncovered history of the Quebec photobook. Consisting of publications prior to 1980, this history can be summarized in a few legendary books, the number of which is easily counted on one hand. Thumb: Où la lumière chante (1966). Index finger: Les ouvriers (1971). Third finger: Open Passport (1973). Ring finger: Disraeli (1974). Pinkie: Transcanadienne sortie 109 (1978).2 If I’ve forgotten any, I still have my other hand.

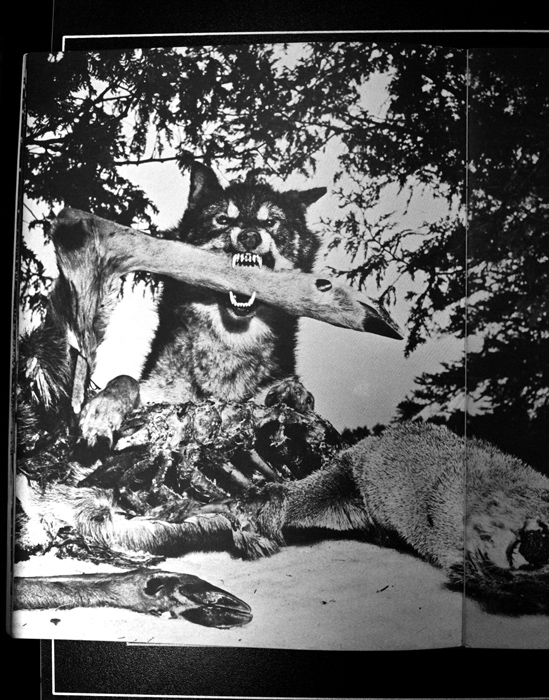

With Visages du Québec in my hands, however, I had to take a small step back to appreciate Cognac’s 1962 book, Guerre aux loups ! 3 In that self-published photographic report, Cognac showed pictures of cadavers of wolves frozen by the cold in order to deliver a dreadful defence of the slaughter of these animals by strychnine poisoning. Although I felt profound indignation in reading about the mass extermination of this magnificent species, which had been ordered by the young minister of hunting and fisheries,4 the book nevertheless contains stunningly powerful images, making it a small gem of photographic mise en scène and an UFO in the desert landscape of the history of the Quebec photobook.

On the whole, the theme of country dominated the few books that covered the scrawny skeleton of this history with a bit of flesh. And that’s really no surprise. As the Quiet Revolution was in its infancy, the quest for country had not yet been subjugated to the partisan interests of politicians, and collectively we were still proud to belong to a land; we knew that all that remained, as the song went, was to name it. The photographer Michel Régnier made perhaps the most complete portrait of this land and its inhabitants. Our first glance at Régnier’s pictures, like those in Visages du Québec, gives a certain sense of déjà-vu. This sense fades, however, when we take account of the fact that these books were published prior to the now-institutionalized folklorization of our history that our colonized society sometimes masochistically surrenders to.

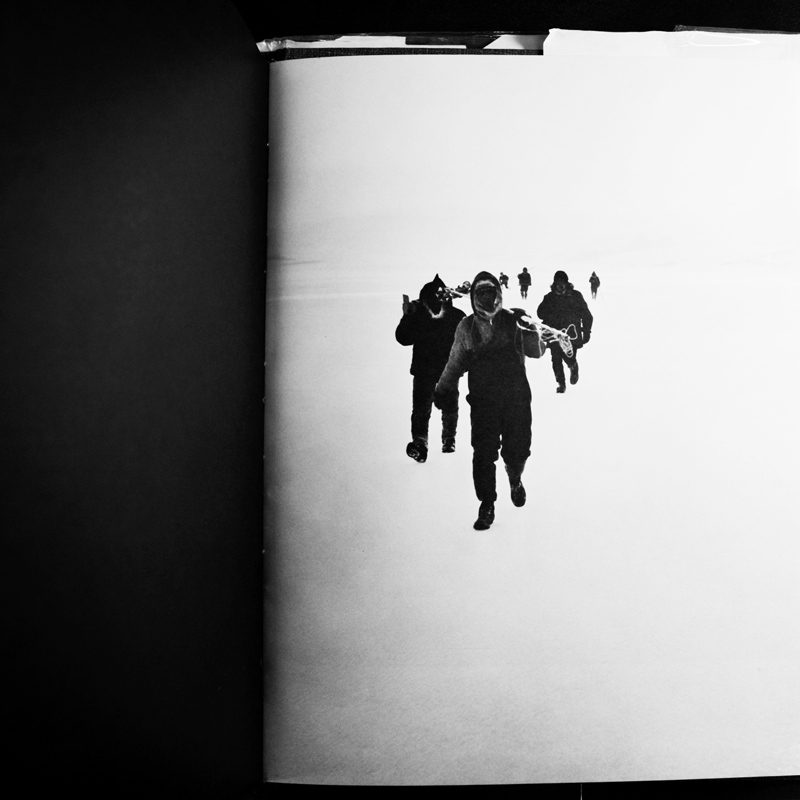

French-born Régnier left his mark in Quebec culture, among other ways, as director of the important activist short film Griffintown, produced by the National Film Board (1972). Régnier’s concern with the gentrification of working-class Montreal neighbourhoods, as expressed in this film, was rooted in his longstanding interest in Quebec’s largest city, which we can assess by looking at his book Montréal, Paris d’Amérique,5 published in 1961. This bilingual book brings excerpts of works by twenty-two Canadian poets, including Félix Leclerc, Roland Giguère, Saint-Denys-Garneau, Louis Dudek, into dialogue with an impressive photographic corpus that transposes the humanist aesthetic into the streets of Montreal. The “Paris of North America” portrayed by Régnier is a city shaped by the juxtaposition of transitory symptoms of North American modernity against the persistent manifestations of a French Canadian culture more and more isolated in the past.

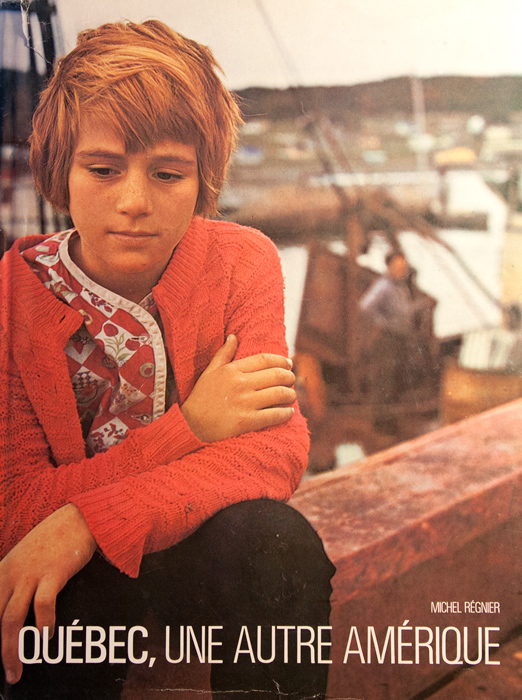

Québec, une autre Amérique,6 published in 1970 and thus approximately contemporary with La Nuit de la poésie and the October crisis, offers a panoramic vision of Quebec society, motivated by Régnier’s stated desire to share his mad love for his host country. Surveying Quebec from east to west and south to north, Régnier deconstructs the territory into a series of photographs that, through an accumulation of often anecdotal representations of daily life, numerous sublime landscapes, and portraits of introspective faces, offers a fairly complete description of the socio-economic reality of the time. It is worth underlining the presence of Aboriginal nations in the final pages of the book, as the Aboriginal condition was presented as an integral part of the Quebec cultural mosaic – still too rarely the case today. The book was also uniquely important because it seems to have been one of the first significant efforts to reverse the hierarchy of text over image, leaning unequivocally in favour of the latter. Despite the relatively connoted portrait of Quebec that Régnier offered, this book therefore prefigures the milestone books Les ouvriers, Open Passport, and Disraeli, which we can legitimately consider the first books by Quebec photographers freed of the grasp that text usually holds on image.

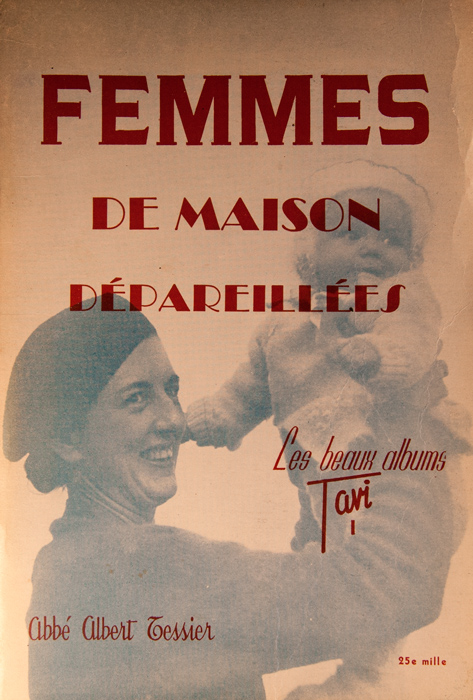

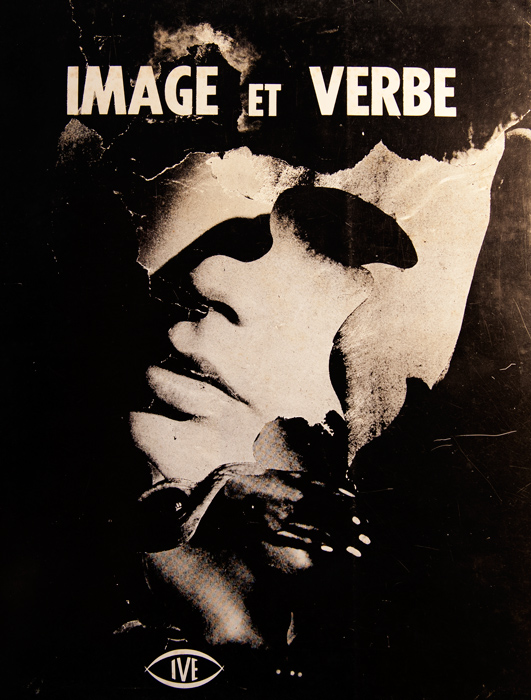

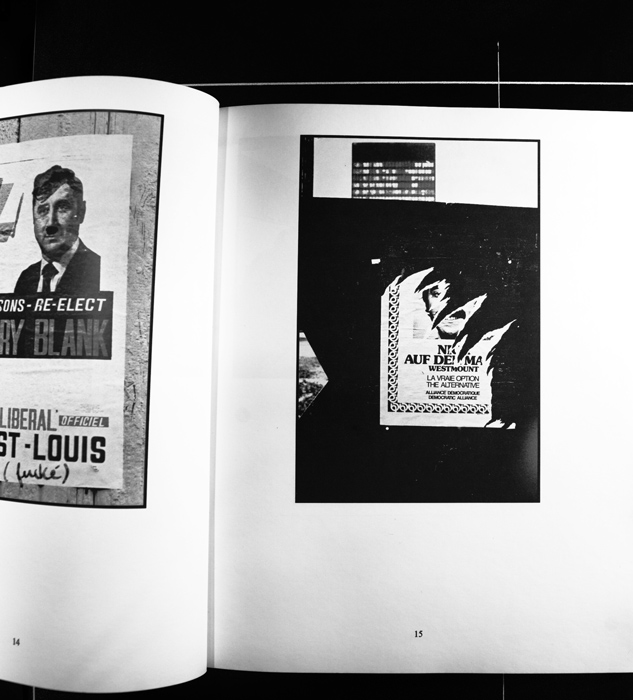

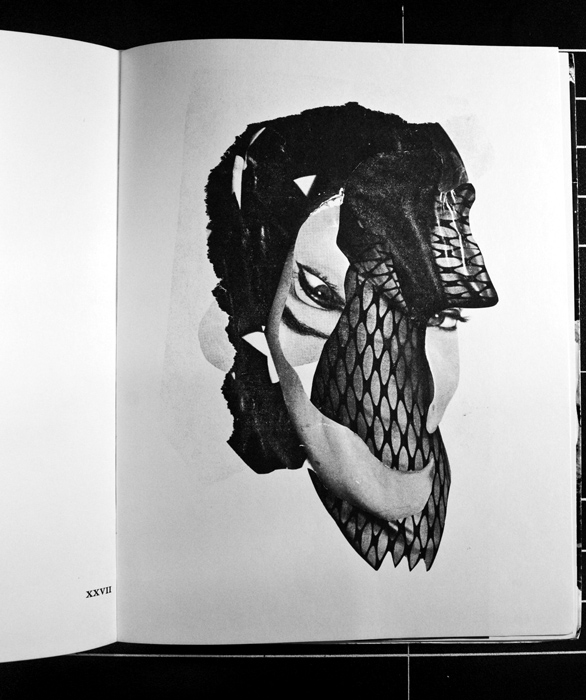

Although they were still dependent on this hierarchy, it is nevertheless important to recognize the contribution of several other publications to the genesis of the history of the photobook in Quebec. First, we owe to Father Albert Tessier, pioneer of the Quebec documentary film, the six volumes in the “Les beaux albums Tavi” series, published by Fides between 1942 and 1946; these programmatic books, with photographs by Tessier, are clearly concerned with propagating the era’s regionalist Catholic values. Tessier’s photographs had previously been used to illustrate a book of poetry by Rina Lasnier called Images et proses (Les Éditions du Richelieu, 1941). The anthology Refus global (Éditions Mythra-Mythe, 1948) included the famous photographs by Maurice Perron of Françoise Sullivan’s Danse dans la neige. Then there’s Roland Giguère’s Images apprivoisées, published by Éditions Erta in 1953, consisting of a series of “provoked” poems and, as the author states, appropriate photographs similar to those that illustrate certain French surrealist publications. In the wake of this book, the photo album Image et verbe (Image et verbe éditions, 1966) contained poems inspired by thirty photo-collages by the Abitibi artist Irène Chiasson. Finally, there are Où la lumière chante, by the Quebec City photographer François Lafortune, and Québec et l’Île d’Orléans (Éditions du Pélican, 1968), by Mia and Klaus. Taking an approach similar to Régnier’s, these two books included poems by, respectively, Gilles Vigneault and Gatien Lapointe.

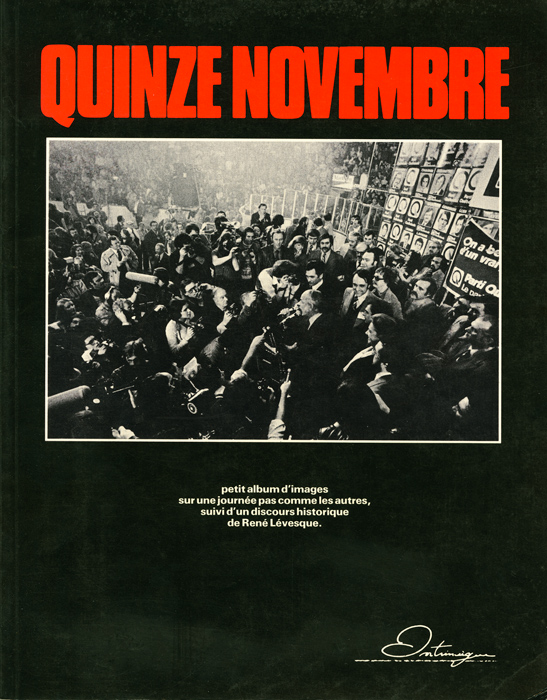

To conclude this admittedly incomplete overview of the origins of the photobook in Quebec, I must slip Quinze novembre (Éditions Intrinsèque, 1976) in between the masterful Disraeli and the powerful Transcanadienne sortie 109, two relatively well-known works. As its title would lead us to guess, Quinze novembre relates, from morning to night, the day of the 1976 provincial election that brought René Lévesque’s indépendantiste party to power for the first time. Produced by a collective of seven photographers who seem to be photojournalists, the body of work in this book takes us from Montreal polling stations to a few Parti Québécois (PQ) campaign offices, and then brings us into the frenzied, smoke- filled atmosphere of the mythic Paul-Sauvé Arena. The exhaustive photographic description of this extraordinary day captures the historic nature of the PQ’s electoral win for Quebec indépendantistes at the time. The palpable joy of the victorious candidates, and of the hordes of supporters who had packed the arena’s stands, conveys the certainty at the time that one day in the not-too-distant future Quebec’s independence would finally be achieved. Intended to commemorate this election, the book ends with a transcription of the vibrant speech delivered that night by Lévesque: “We aren’t a small people; we are perhaps something like a great people.” Looking through these pages and reading these words almost forty years later, we have a better understanding of how, despite the referendum failures of 1980 and 1995 and a pronounced shift from social democracy to neo-liberalism, the PQ is still able to systematically dupe voters, who persist in thinking that its desire to contribute to the political emancipation of the Québécois people is genuine.

My motivation in writing this overview of the as-yet-uncovered history of the Quebec photobook before 1980 wasn’t to offer an exhaustive excavation of this history. A thorough comprehension would require a much greater investment of energy than I have devoted to it so far, and this research remains in large part to be conducted, by me or by others. Rather, I wanted to offer some thoughts, as imperfect as they are, on the subject in the hope of seeing this history, still embryonic, gradually enhanced with scholarship that will provide the Quebec photographic publishing sector with a solid historic foundation.

Outside of Quebec, since the early 2000s historical publications testifying to the importance of the book in art photography have flourished. These books have made it possible to acknowledge and legitimize a set of innovative publishing practices centred on photography, and they have contributed to the exponential growth of a book market from which Quebec artists are relatively absent. Despite the quality of the photographic work being produced in Quebec today, production of photobooks is relatively marginal here, mainly for two reasons. First, the lack of in-depth scholarship on the history of photobook publication in Quebec makes it difficult to recognize this autonomous form7 of photographic creativity and create a readership sensitive to its specific issues. Second, although Quebec society has implemented public funding structures that enable culture to exist without being completely subjugated to the pecuniary imperatives of the world art market, the production of Quebec photobooks is not favoured by the funding programs currently in place, which see artist books principally as a means of promoting individual artists’ careers rather than as a full-fledged creative form. Thus, visual arts publishing initiatives are forced to mould their products to the fundable model of the monograph and to bow to the precedence of text content over visual content in publications. It goes without saying that this conception of the artist book is incompatible with the stakes in production of photobooks.

Confronted with these difficulties as a practitioner interested in working in this particular creative field, I feel that it is important to participate, to the best of my capacities, to its historical recognition in the hope that one day this recognition will be echoed in the public funding policies for Quebec culture. This hoped-for funding is even more necessary given the dazzling expansion of the world market for photobooks. Quebec artists who wish to produce such books in the future will face a difficult dilemma given the lack of adequate public support: to produce their books abroad rather than in Quebec or to sacrifice the use of the French language to American domination of this market. In either case, Quebec culture will certainly be on the losing end.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 François Lafortune and Gilles Vigneault, Où la lumière chante (Quebec City: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1966); Pierre Gaudard, Les ouvriers (Ottawa: Office national du film, 1971); John Max, Open Passport (Toronto: Impressions, 1973); Claire Beaugrand-Champagne, Michel Campeau, Roger Charbonneau, and Cedric Pearson, Disraeli, une expérience humaine en photographie (Montreal: Les Publications de l’imagerie populaire, 1974); Jean Lauzon and Normand Rajotte, Transcanadienne sortie 109 (Montreal: Les Éditions OVO, 1978).

3 Marcel Cognac, Guerre aux loups ! (N.P.: Éditions Marcel Cognac, 1962).

4 Sanctioned on 14 March 1962 by the Liberal government of Jean Lesage, the statute creating the department of hunting and fisheries was contemporary with the publication of Guerre aux loups !

5 Michel Régnier, Montréal, Paris d’Amérique (Montreal: Éditions du Jour, 1961).

6 Michel Régnier, Québec, une autre Amérique (Quebec City: L’éditeur officiel du Québec, 1970).

7 Alexis Desgagnés, “John Gossage, the Photobook: Reflections on Several Recent Projects,” Ciel variable, No. 95 (autumn 2013), 62–66.

Alexis Desgagnés lives and works in Quebec City. His research addresses photographic theory and practice from a dialectical angle. His photographic work has been exhibited at L’OEil de poisson and Regart (Quebec City), as well as in various magazines. A regular contributor of essays to Ciel variable, Desgagnés is a lecturer at the Université de Montréal and Université Laval, and he is artistic director at VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie.