Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris

6 September to 18 October 2014

By Stephen Horne

David Goldblatt has been photographing in South Africa for many decades. The acuity with which he has recorded the depths of violence and its specific character both during and after the era of apartheid rests on his observation of violence naturalized. Structures of Dominion consists of fifteen black-and-white mid-sized photographs, most taken in the 1980s, and the ten images in Structures of Democracy were taken starting five years after the first democratic elections were held.

For many decades, Goldblatt has been concerned with the particulars of daily life in South Africa, and with photographically recording the meanings he finds in this place. He was born in South Africa in 1930, and his lifelong documentary project has resulted in the production of a substantial archive. This exhibition presents his project recording the evolution of what he calls the structures of dominion, on the one hand, and of democracy, on the other. This body of work has been shaped according to his selection of a single subject, that of buildings and monuments, an architecture. He believes that with such a focus we can observe the “values” of a people – in this case, the attitudes and practices of a minority white society in a colonized and resource-rich landscape.

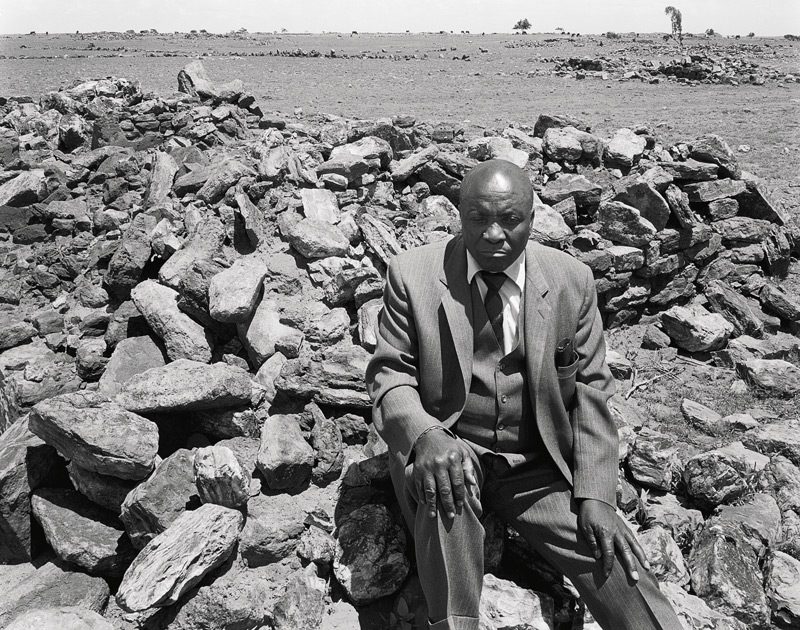

One photograph presents a man in a suit and tie sitting in a pile of rocks and rubble. The man and the rubble more or less fill the frame, although a small slice of prairie and a horizon cross the upper limit of the picture. This man’s feet are outside the lower edge of the photograph. He is thus inclined toward us, with his gaze directed at the camera. His hands rest on his knees. He is a black man of advancing years. He has perhaps simply stopped at this rock pile to rest or to pose for the photographer.

As is the case with all the photographs in this exhibition there is a substantial caption, in this case one identifying the man as Luke Kgatitsoe and telling us that the pile of rocks is what remains of his house, destroyed by the government of Transvaal Province as part of a “forced removal” project. With its understated simplicity, this image crystallizes a world based on oppression, an arrangement in which abuse of power is the everyday norm. Sitting on what was once his evidently already simple housing, Luke Kgatitsoe’s prospects appear dire and place him in the company of other modern “relocations” and “disappearances.”

A second paragraph in the caption describes the practice in which valuable farm land is cleared of black owners and tenants in order to be made available to white farmers. Such were the “values” of the epoch. This photograph is dated 1986, eight years before the formal ending of white minority rule.

Such a narrative is no doubt familiar to Canadian audiences, the system of forced relocation onto “reservations” having been rigorously and widely applied to Canada’s indigenous peoples. It is widely held that the Canadian system of “reservations” and segregation of indigenous peoples served to inspire the authorities of South Africa as they extended their domination with the application of similar practices.

Goldblatt photographed the scene near the Lonro platinum mines following the shooting of over a hundred striking mine workers by police in 2012. In the foreground, rising from a patch of bushy long grass and rocks, several simple white wooden crosses, some standing, some fallen, mark and commemorate those killed. The view looks uphill, and just over the crest of this ridge large electrical transmission towers make their connection to the Lonro smelter. With his characteristic independence, Goldblatt challenges any easy perception of progress after the overcoming of apartheid. Just as this photograph presents the mine facilities behind the murder scene, we are encouraged to contemplate the persistence of capital with its executives and shareholders, now multinational and distant, who call the shots.

Such is Goldblatt’s landscape. Until recently he has presented it in black-and-white prints, although there are two colour prints in the exhibition. They are “before and after” photos of Freedom Square, Soweto in 2003 and in 2006, with the location renamed Walter Sisulu Square. In the first image, the square is an open “people’s place”; in the second, the open market ground has been replaced with an authoritative new facility, now resisted and rejected by the square’s former users, who, no doubt, are all too aware of the coercive powers of such “structures.”

If Goldblatt sees these buildings and places as expressing the normalization of coercion and corruption as acceptable ways of life, his response is that of photography practised as a means of interruption and denaturalization. His is one of the world’s great projects of documentary reportage and, as such, is clearly distinguishable from the interventions of Edward Burtynsky, Alfredo Jaar, and Sebastiao Salgado, whose practices rest on pictorial aesthetic practices deriving from painting. Goldblatt distinguishes himself from this tradition, referring to himself as a “craftsman.” In his photographs, we face the paradox of the simultaneous engagement and detachment that the documentary perspective evokes. The remarkable achievements of his practice recognize the unfolding of actuality in its duration.

Stephen Horne lives near Paris and writes on contemporary art for publications in Canada and abroad.