National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

27 June to 16 November 2014

Par Johanna Mizgala

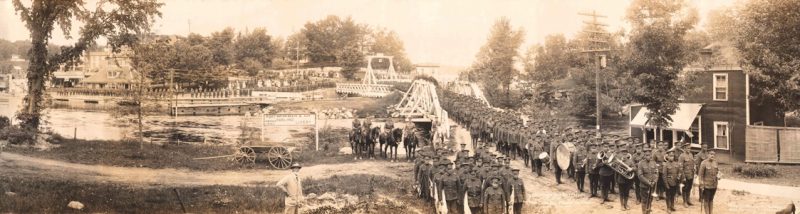

The Great War: The Persuasive Power of Photography contains over four hundred images, ranging from private portraits to almost-life-size enlargements of battlefields and scenes from the front. The exhibition addresses the multiple means by which photographs circulated during the war years, while at the same time underscoring the profound sense of loss and devastation experienced by a generation and its descendants. Poignant, lyrical, and, at times, grisly, the photographs offer glimpses into the sheer magnitude of this moment from our collective past.

Photography had been in existence for over seventy-five years at the outbreak of the First World War. From its inception, the medium had been employed to record both the battlefields around the globe and the faces of soldiers. Just as the cumbersome equipment of the early years was a determining factor in the kinds of images that could be created, so too were the rules of modesty, decorum, and restraint – careful consideration was paid to how the public might react to certain scenes, as well as to conveying and circulating the values of honour, dignity, and valour. From the beginning, it was clear that the medium was a powerful message. Censorship was tightly adhered to, as it was crucial that those at home remain steadfast in the conviction that victory was close at hand; although their loved ones were in harm’s way, they clung to the belief that soldiers were well looked after by those in command. Letters home and personal diaries contradicted the majority of the official images, which showed smiling, jovial young lads who seemed to be having a grand time.

The confluence of advances in photographic technology, access to information through forms of mass communication, and the burgeoning use of the camera by amateur photographers in the early years of the twentieth century created a new visual landscape and a greater appetite for wartime images: photographs were created and disseminated not only for official purposes, but also by the press and for circulation in private hands. Photography pervaded all avenues of military life, although still according to tight constrictions: photographs in personnel records; images of training facilities, military equipment, camps, and numerous group portraits; aerial photographs for reconnaissance purposes; illustrations for news items that were sent home and to the front; and personal treasures that helped to span the distances by keeping the faces of loved ones close while they were gone for long years.

Included in The Great War: The Persuasive Power of Photography are a series of modern prints, created for the exhibition, from war-era autochromes by French photographer Léon Gimpel. Gimpel’s images, taken in 1915, depict a group of Parisian children, some of whom likely had male relatives on the battlefront, acting out skirmishes of their own in their neighbourhood streets. Dressed in costume and wielding toy weapons, the children play at war, drawing their inspiration from stories that they have overheard in adult conversations. The images are at once whimsical and sobering, evidence of how the Great War permeated the imaginations of everyone, including children, who could not fathom the depths of the devastation but nonetheless were captivated by its omnipresence.

Photographs from war zones belie the medium’s claims to the unerring power of truth-telling: they cannot adequately capture the enormity of the events in question, and yet, in its aftermath, they serve as vital evidence to piece together what transpired. They signal events but they cannot contain them, however strong the desire for such closure. Photographs are encapsulations – moments that are selected, framed, and lifted out of time and space. They exist both in history and out of history and serve as much as evidence as invention. They occupy a curious terrain of permanent present – and yet, by virtue of their content, they offer the viewer a glimpse into something that once was. As visual arguments, they propose a point of view that requires a willing viewer who understands their signs and symbols. As aesthetic objects, they command a presence in their own right, while simultaneously serving as traces of action that transpired in the past.

The National Gallery installation includes a re-creation of an exhibition held in 1917 at the Grafton Galleries, London. The Grafton show was one of several events organized through the Canadian War Records Office, the brainchild of Sir Max Aiken, who would become Lord Beaverbrook. Aiken considered photography essential to documenting Canadian involvement in the Great War and held firmly to its persuasive powers for promoting the war effort. Visitors to the Grafton Galleries were treated to the spectacle of huge reproductions of images of war, including one that took up an entire wall, reminiscent of a movie screen. The goal was to make viewers feel like they were part of the action and to rally emotions to the ongoing cause. Accompanying the exhibition was a checklist of images, and patrons could order copies of the photographs.

In the contemporary installation, the photographs call to mind not only modern large-scale photographs in which the artist is clearly playing with and calling into question the seductive abilities of scale, but also reference mass advertising campaigns in the form of billboards. Added to this context is the knowledge that several images were in themselves re-creations of events or staged scenes, or else were printed using multiple negatives from different points of view. At the time of the initial presentation, this sometimes-elaborate mise en scène would be understood simply as the most economical means by which it was possible for the photographer to produce the images, given the realities of carrying a camera in media res onto the battlefield. Viewed with the luxury of distance, however, the images lose some of the immediacy of action. Their seductive powers necessitate a measure of complicity. Each successive generation of viewer, having less and less direct interaction with the actual events, imbues the images with greater significance, as the key to understanding; yet by this very contradiction, the photographs operate more as fictionalization than simple facts. Nostalgia and history are strange bedfellows.

Johanna Mizgala is the curator of the House of Commons Collection and a PhD candidate in cultural mediations at Carleton University. Her interest in commemoration and the persuasive power of photography stems from a longstanding investigation of memory and photography, of longing and loss, and of identity politics.