[Fall 2024]

The Artist as Avenger

by Cheryl Simon

What I am doing is contextualizing my family’s experience. This is what they witnessed in their lifetimes, and this is what I wanted to put forward. This is the stuff that they’ve internalized, more importantly. And so being able to manifest it and put it out in the world so that people can see what they witnessed, what they experienced – it’s a means for me to avenge my family, so to speak. I use that language very certainly. They have been wronged historically and so this is an opportunity to right them in a very real, very public way.

– Deanna Bowen1

The Golden Square Mile, Deanna Bowen’s exhibition at Concordia University’s Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery in Montreal,2 expands on themes and strategies that she has explored before, notably in The Black Canadians (after Cooke) (2023), her extensive and contentious photo-based mural installed on the façade of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.3 Whereas for this project Bowen assembled archival materials to trace the intersecting narratives of race politics and policies in North America and the establishment of Canada’s cultural institutions from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, the images and ephemera presented in The Golden Square Mile delved into the social, political, and economic foundations of the identity that these productions informed. Specifically, the installation tied the status, wealth, and cultural traditions of Anglo-Canadians in Montreal to the colonial relations between Canada and the British Empire during the same period.

Characteristic of Bowen’s practice, both of these exhibitions drew material from a wide array of archival sources, presented in constellation form and curated to challenge official historical accounts about Canadian identity, providing evidence supporting a different, more complex experience of belonging. In particular, they honoured the historical experiences and personal narratives of Bowen’s own family forebears, bearing witness to the events and circumstances that they would have observed and endured as Black immigrants to this country, with historical references covering a period beginning with her great-great-great-grandfather’s birth in Africa in the late 1700s and ending with the birth of her mother in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century – a span of approximately 150 years.

Telling a complicated, difficult, and highly charged story, the Ottawa project juxtaposed portraits of royalty, politicians, abolitionists, and Indigenous leaders with images of decimated landscapes, slave shackles, and tattoos. It also highlighted resistance to Black and Jewish immigration and the presence of white supremacist organizations in Canada, with pictures of political figures responsible for restrictive entry policies and the design and implementation of the residential school system presented alongside snapshots of a Ku Klux Klan Imperial Council in Vancouver in 1925 and of the Right Honourable W. L. Mackenzie King sitting with a Nazi officer at a sporting event in Berlin in 1937. Because these images were mixed with those of artists, art historians, and art organizations active at the same time, the mural drew connections among what are often seen as competing stories shaping Canadian history – of empire and nation building, emancipation and oppression, heroism and violence.

The Black Canadians (after Cooke) stirred controversy. Some members of the press took the opportunity to decry the Gallery’s promise to decolonize the museum and cited Bowen’s commission as an example of the kind of ruinous historical revisionism to be expected of this liberating turn. Others raged against the use of tax dollars to fund an artwork calling out the country’s racist past.4 Writers to the letters section of an online art journal debated the factual accuracy of Bowen’s chronicle, with particular concern that the reputation of the Group of Seven had been damaged by insinuating ideological associations.5 A few recognized the landmark significance of Bowen’s work, acknowledging its value for Gallery visitors and cultural workers who may have seen their own experiences reflected in the story the mural told.6

The Golden Square Mile did not generate the same level of debate. Although it also opened up official narratives to expose the complex workings of power and politics that shape Canadian culture and society, it was oriented very differently. Bowen’s installations are typically site-specific and this exhibition was no exception. Whereas the positioning of The Black Canadians (after Cooke), on the façade of Canada’s national museum and in view of Canada’s Houses of Parliament, informed its particular attention to the politics of nations and national culture, the setting of the exhibition at Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, between the former mansions of Montreal’s elite and the past jazz clubs owned and operated by its Black communities, dictated a different emphasis. The focus was on how social relations and power positions are negotiated on the playing fields of popular culture.

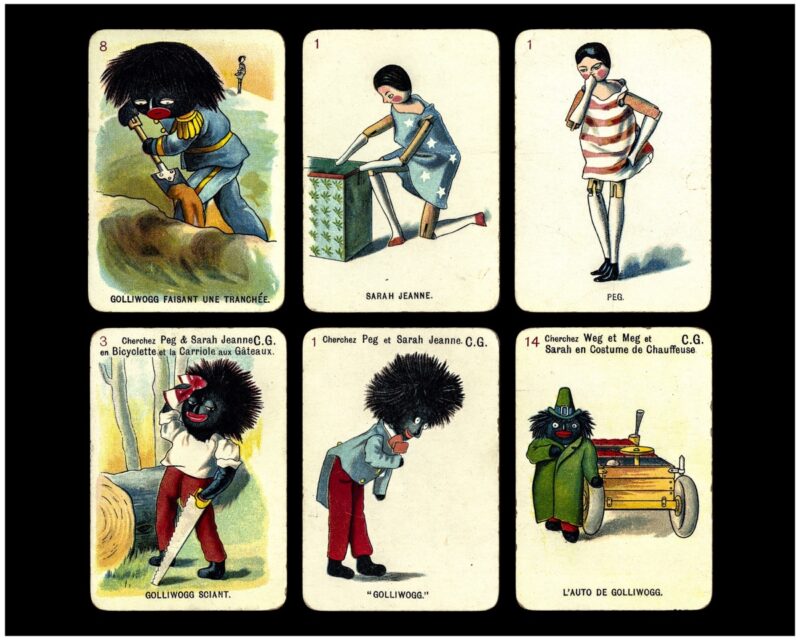

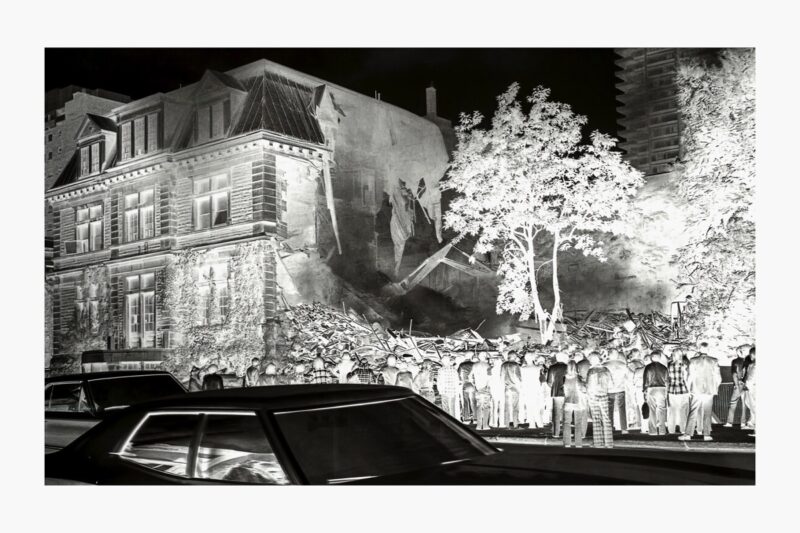

The exhibition in Montreal intertwined photographs sourced from local newspapers, civic groups, and military archives with imagery and ephemera drawn largely from media and entertainments common in the city during the early and middle parts of the twentieth century. Memorabilia and illustrated newspapers commemorating the visits of the royals to Canada joined postcard-type views of Montreal mansions, PR for theatrical productions and minstrel shows, illustrations on playing cards and in storybooks, and a remarkable array of caricatures. Although the historical narrative captured in this fusion straddled class and culture, on balance it demonstrated the prevailing social attitudes and cultural interests of the elite community of Montreal’s renowned Golden Square Mile. From the mid-1800s to the turn of the twentieth century, this area in downtown Montreal was the epicentre of Canadian power, inhabited by influential figures such as railway barons, shipping magnates, newspaper publishers, industrialists, and bankers, many of whom were of Scottish descent and some of whom held knighthoods. These individuals controlled 70 percent of the nation’s wealth, moulding its cultural heritage – a legacy that was deeply entangled with imperialistic ideals.

It is well known that Canada’s prosperity owed a debt to Britain, and yet its economic dependence on the colonization of other nations and tacit military support for Britain’s colonial expansion elsewhere are seldom mentioned. Similarly, although it is common knowledge that colonization had different implications for racialized and Indigenous peoples than for white Europeans, open dialogue about this situation is still relatively uncommon. Moreover, the role that cultural production performs in maintaining and reproducing but also resisting this differential is rarely discussed. The Golden Square Mile leaned into these conversations, with the intersections of war, class privilege, race, and representation operating as its principal critical motifs.

Bowen’s opening gambit was enigmatic: a thirty-plus-foot photographic reproduction of a player-piano roll stretched to fit the full length of the gallery’s vitrine introduced visitors to a thematic concern that was threaded throughout the exhibition. From outside, it was unclear what it was, although the punch-holes in the paper hinted at its automating function. The object and its significance were better understood once inside the gallery. A reproduction of Bowen’s Smoky Mokes Cake Walk Piano Roll (2024), the piece announced the stakes to be won and lost in the contest that the exhibition staged: the annexation and financial exploitation of cultural forms and identifications. “Smoky Mokes Cake Walk,” a ragtime number written by Tin Pan Alley composer Abraham Holzmann, represents an early instance of cultural misappropriation: a white interpretation of a Black musical form, originally conceived to mimic white social manners. Originating in the African American community during the late nineteenth century, the cakewalk was a dance with roots in plantation gatherings and slave traditions. It involved couples in a dance competition parodying the social airs of plantation owners, with a cake as the prize for the best performance. Later, when taken up by white culture in minstrelsy, the cakewalk adopted the dance movements in mockery of Black culture. If, as Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) suggested, “The idea of white minstrels in blackface satirizing a dance satirizing themselves [is] a remarkable kind of irony,” it condenses, in miniature, the kind of struggle for power over self-definition and identity that unfolds in the spheres of the popular.7

As emblem and refrain, the cakewalk permeated the entire exhibition. Reproductions of cakewalk sheet music and album covers and photographs of cakewalk performers and performances appeared in different constellations throughout the show, with a two-part video installation showing historical documentation of Black and white cakewalk performers – slowed to exaggerate the dancers’ stylized movements – ending the exhibition’s tour. Most affectingly, the strains of Oscar Levant playing Claude Debussy’s piece “Golliwog’s Cakewalk” filtered throughout the exhibition space, colouring viewers’ encounters with each and every constellation. Characterized by regular and syncopated rhythms, the music made one kind of sense when regarding groupings of music-themed materials – posters, portraits, and PR shots of local musical legends and theatrical performers – and another when looking at the pictures of degrading minstrel performances juxtaposed with horrific Golliwog caricatures from children’s storybooks and playing cards, and yet another when looking at the photographs that referenced the Anglo-Zulu war, the sugar plantations in Jamaica that supplied the sugar for Canadian refineries, or the detention shed that housed the Chinese workers who built the Canadian railway. In the first instance, the rhythm seemed to unfold as a jazz composition might, with the syncopated notes acknowledging the difference in attunement required of each individual image. One was primed to look for the exceptional honorific image – and there were plenty to be found, especially in the group portraits. When confronting images presenting humiliating stereotypy that had been produced, it would seem, to justify the violence of colonial enterprise, the tune soured, with the syncopation sounding more forced and automated, like the disembodied and unrelenting press of industrial production rather than the call and response of musical innovation.

Bowen introduces herself as “an artist, an educator, and a rabble-rouser.”8 She might have added “community builder.” Despite all the painful histories and truths that her works have uncovered, she remains fully dedicated to the possibilities that the past may hold for the present and future. In her view, if decolonization means anything it means opening the museum to new voices and the archive to new discoveries: placing history in the hands of the people for whom it might matter most. Considering the subject matter addressed by her work, the celebratory spirit generated by the events staged around her exhibitions may come as a surprise. The official launch of the Ottawa mural coincided with Emancipation Day, held on the actual date in 1834 on which the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 came into effect. Members of Black History Ottawa, a charitable organization committed to advancing knowledge of Black cultures and histories, were invited to participate in the opening and celebration, and hundreds attended, some entering the National Gallery for the first time. In Montreal, a jazz performance by the Charles Ellison Quintet at the exhibition’s closing brought contemporary jazz fans into contact with the storied past of the city’s musical culture. And, during the course of her exhibition at Concordia, Bowen invited a group of students to speak about their own archival investigations – to a standing-room-only crowd!

In a public conversation with Bowen, Désirée Rochat, the Concordia University Library’s researcher-in-residence, proposed that the rhythms of the exhibition captured something of the spirit of resilience of Montreal’s historical Black activist community, and also their joy in celebration. It is a remarkable feat to keep history alive, to push back and resist social oppression and cultural assimilation, to build community and bring joy, all at the same time. Rabble-rouser, indeed!

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: The Artist as Avenger]

NOTES

1 Deanna Bowen, “Becoming Deanna Bowen,” uploaded to YouTube by the National Gallery of Canada, July 11, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bq2OeKUKlMY&t=250s. Bowen is discussing her mural The Black Canadians (after Cooke).

2 The Golden Square Mile, curated by Michèle Thériault, Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, February 21–April 13, 2024.

3 The Black Canadians (after Cooke), curated by Jonathan Shaughnessy, National Gallery of Canada, Summer 2023–Fall 2024.

4 See Sophie Durocher, “Bande de racistes !,”

Le Journal de Montréal, June 28, 2023, https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2023/06/28/bande-de-racistes; James Sarkonak, “National Gallery Trades Accuracy for Diversity,”

National Post, July 30, 2023, https://nationalpost.com/opinion/national-gallery-trades-historic-accuracy-for-diversity.

5 See Paul Gessell “Contradictory Truths?,”

Gallerieswest, July 17, 2023, https://www.gallerieswest.ca/magazine/stories/contradictory-truths/, and “Debate Grows Over Installation at National Gallery of Canada,” August 2, 2023, https://www.gallerieswest.ca/news/debate-grows-over-installation-at-nat/.

6 See Gabrielle Moser, “Deanna Bowen: National Gallery of Canada,”

Artforum, December 31, 2023, https://www.artforum.com/events/gabrielle-moser-deanna-bowen-national-gallery-of-canada-2023-545549/; Barbara Fisher, “Guilt by Association, or by Complicity?,”

Gallerieswest, n.d. https://www.gallerieswest.ca/guilt-by-association-or-by-complicity.

7 Amiri Baraka,

Blues People: Negro Music in White America (New York: William Morrow 1963), 86.

8 Bowen, “Becoming Deanna Bowen.”

The author

Cheryl Simon is an academic and writer whose current research interests include algorithmic art and internet culture, photography and the archive, media archaeology, and changing modalities in screen-based art practices. She teaches in the MFA-Studio Arts program at Concordia University and in the Cinema + Communications Department of Dawson College, both in Montreal.