[Fall 2024]

Casa Susanna

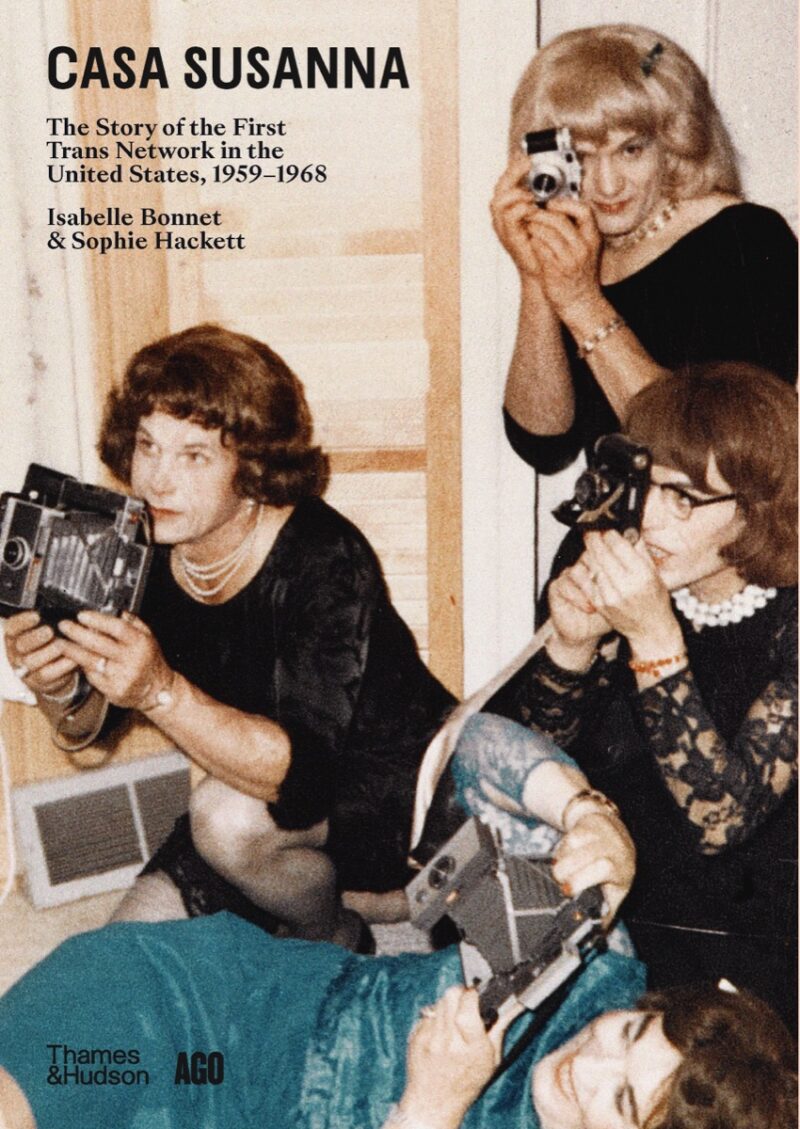

by Dayna McLeod

Casa Susanna is a tremendous showcase of mid-twentieth-century photographs of a femininity-celebrating community of crossdressing men, trans women, and gender-nonconforming people in upstate New York.1 Fortuitously recovered from a New York flea market in early 2000s, the images published in this hefty volume allow us to travel back in time to visit a devoted community and glimpse their joy in celebrating and photographing each other in women’s attire. Subjects smile and pose for the camera, snapshot style, in solo portraits and group shots in living rooms, kitchens, porches, and front yards. Perched on a fence, poised by a wagon wheel, or seated on a couch, chair, or stool, they’re always showing off their best side.

These images, filled with delight and confidence, tell the story of kinship, care, intimacy, celebration, and camaraderie. The sheer volume of the collection reinforces the reach of this dynamic network: every picture glows with self-assurance and femininity. Compelling essays by the acclaimed American trans history scholar Susan Stryker and exhibition co-curators Isabelle Bonnet and Sophie Hackett introduce this incredible immersion into life at Casa Susanna.

A selection of covers from Transvestia, a magazine first published in the 1960s that catered to the crossdressing community and later expanded to include interests relevant to the broader trans community, complement this collection of Catskill candids.2 As the essays in the book make clear, Transvestia’s readership and Casa Susanna’s community overlapped with and reinforced each other. An article by Transvestia’s publisher and editor, Victoria Prince, explains her approach to the magazine, whose tone and style were further exemplified by short beauty articles, fashion spreads featuring contributors, and personal ads, all regular features. An autobiographical piece by Casa Susanna proprietor Susanna Valenti, a regular Transvestia contributor, details her awakening as Susanna, her struggles with dressing in women’s clothing, and the loving support of her wife, Marie. Susanna is found in photographs throughout the book as she welcomes guests, poses proudly, shows some leg, and smiles up a storm.

Stryker contextualizes Casa Susanna’s history in mid-century America. She also explains that she “didn’t really identify with the traditionally feminine notion of womanhood that Casa Susanna’s regulars aspired toward” and that these community members “were gendernauts who explored themselves with others, experimenting with different realities, trying them on for size, figuring out how to make them work.” Further on she reflects, “As I look back with my historian’s eye, I see them not only expressing their positive desire for femininity but critiquing what it means to be a man in their day and age.”

Bonnet details the high stakes of crossdressing for men in the Cold War period, which was “marked by a climate of paranoid suspicion toward all gendered or sexual behaviours that were considered non-conforming.” Bonnet illuminates how Transvestia and Casa Susanna advocated for and practised privacy-protecting conventions throughout their networks because of the dangerous reality that any form of gender deviance was treated as sickness or crime. Bonnet also discusses the lives and politics of Victoria Prince and Susanna Valenti and their impact on the crossdressing community, including the outspoken transphobic, homophobic, and anti-feminist views that Prince shared in the magazine.

Hackett discusses the pivotal role that photography played at Casa Susanna by serving as a unifying medium and activity. She also talks about Prince’s desire to present “authenticity” in the pages of Transvestia and describes the “aspirational ordinariness” that these images seemed to epitomize. Hackett argues that this reflects a longing for a bygone era of American femininity, which perhaps resonated with members of this community who grew up with mothers, sisters, and other role models whom they had romanticized. However, as Bonnet argues, there is an inherent paradox in this embrace of “conventional female identities” that are “based on a patriarchal vision of womanhood” in which women are objectified and passive. “There is only one kind of female identity depicted in Transvestia, though the specifics vary with age: the girl next door, the devoted housewife, the church lady. The crossdressers’ version of ‘chic’ is classic, discreet, sober; the kind embraced by Ladies’ Home Journal and prescribed by Vogue.” This style of dress and approach to femininity is also reflected throughout Casa Susanna.

Nevertheless, these images are more than simple dress-up photos. They are totems of self-actualization that were essential to the identitary survival of participants when they left the comforts of Casa Susanna and returned to worlds where traditional masculinity, dressed in suits and ties, reigned. These images were shared, often by mail, as keepsakes and touchstones of mutual identity and intimacy, tangible artifacts of identity affirmation. We are so very lucky to witness these people en femme and see the shared joy on each and every one of their faces as they wear their best outfits for just such an occasion.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: Casa Susanna – Dayna McLeod]

NOTES

1 This book accompanied the exhibition Casa Susanna, which was co-produced by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) and the Rencontres d’Arles. It was at the AGO from December 23, 2023 to June 16, 2024.

2 All 114 issues of Transvestia are available online via the University of Victoria’s Transgender Archives collection. This collection also holds magazine founder Virginia Prince’s records. See https://www.uvic.ca/transgenderarchives/collections/virgina-prince/.