[Summer 2025]

Feeling and Listening to Images

by Érika Nimis

[EXCERPT]

By combining photography and textiles, the Cameroonian-Belgian artist Mallory Lowe Mpoka weaves visual stories that explore the blurred boundaries of identity and belonging. She focuses on the way in which an individual may navigate in multiple spaces, constantly redefining what it means to be part of different cultural contexts and to situate oneself within them. Lowe Mpoka, who was born in Montreal in 1996, evokes her own hybrid condition, in constant dialogue with many cultures. As a queer artist, she also addresses dynamics of power and representation through various media by encouraging critical reflection on questions of otherness and decolonization of the gaze. She questions, among other things, the place of nonWestern bodies in dominant narratives by deconstructing stereotypes conveyed through photography, which often fix the Other in a unilateral image.

[…]

In Lowe Mpoka’s practice, the self-portrait takes centre stage and the body becomes a space of resistance, a way to rewrite history; therefore, The Self-Portrait Project (underway since 2021), inspired by her family’s photographic archives, is deeply rooted in the visual landscape and photographic culture of post-independence central Africa and reflects its diasporic realities. Holding in her hands a photograph of her father dating from the 1970s, she tries to re-create her sense of belonging and revive her Bamileke (western Cameroon) heritage, while breathing new life into these archives. From her new position and point of view, she perceives them as an opening, a space where it is possible to reinvent herself from the traces of the past.

Aside from photography and textiles, she uses techniques such as sculpture to create immersive environments. Her most recent textile installation, The Matriarch: Unravelled Threads (2021–24),1 presents a circular structure, lit from inside, composed of several hundred screen-printed images of her family and herself, dyed with the red earth from her ancestral region. Through such combinations, which aim to transform the art experience into a living dialogue between the work and the public, she slowly but surely defined the plan for a first artist monograph, titled Architecture of the Self: What Lives Within Us.2

Behind the plain front cover of Architecture of the Self, illustrated with the black-and-white image of a box into which a jumble of photographic materials have been tossed, Lowe Mpoka deploys great visual inventiveness to celebrate her close ties with her family in Cameroon. Her quest took a decisive turn with the death of her paternal grandmother, in March 2023. In effect, she inherited the role of matriarch of her Bamileke family and has since assumed the responsibility of preserving and passing on her forebears’ memories, especially those conveyed by photographs.

The book opens on a double-page image of a wall made of banco (bricks made of dried clay and straw) pierced with a little window curtained by scraps of fabric, perhaps symbolizing the vulnerability of this familial transmission. Fluently, from page to page, she traces her path among various markers of identity and memory: Bafoutam, the ancestral village, about twenty kilometres from Bandjoun, where she attended an art residency in 2021, at the Bandjoun Station art centre; Douala, where her family has a sewing workshop that she photographed in 2022; Montreal, her hometown, where, in 2023, she posed as the Odalisque during a performance in the form of self-portraits, her gaze turned toward a photograph of her grandmother.

She combines exploratory photography, poetry, personal stories, and reflections supported by references. A section at the back of the book, printed on green paper, provides a translation of the texts into French, including an interview with the Toronto curator Liz Ikiriko. The book’s masterful layout alternates the formats of the images and texts and the colours, and plays with opacity and transparency, openings and ruptures, to underscore the complexity of the family history and of her own quest. She moors herself by inscribing her body, whole or fragmented, into adobe buildings that are deteriorating, just like people and things. Laterite, the red earth that colours even the book’s cover, is a central material. Dyeing and photographing are melded together here, for in both cases imprints are lifted from the earth. No matter what the process, working with this material becomes an act of re-appropriation and transmission. By photographing her hands and feet in contact with the red earth of her forebears,3 she permeates this territory to the point of melting into it.

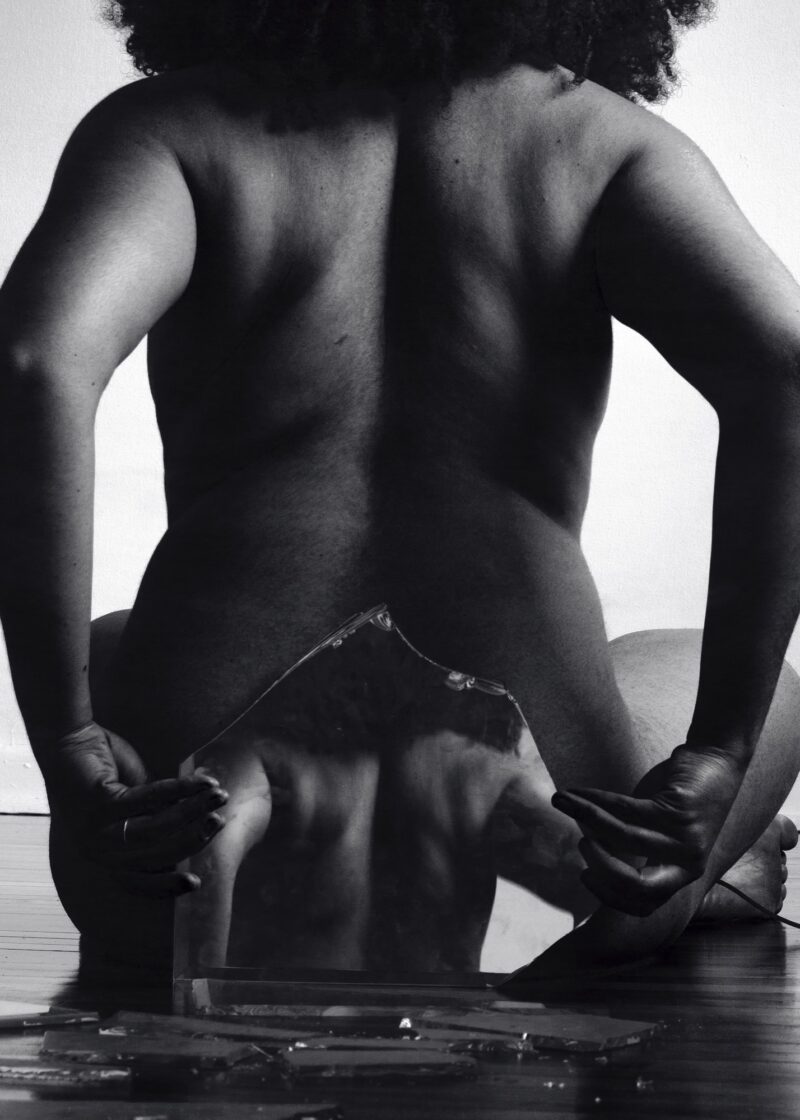

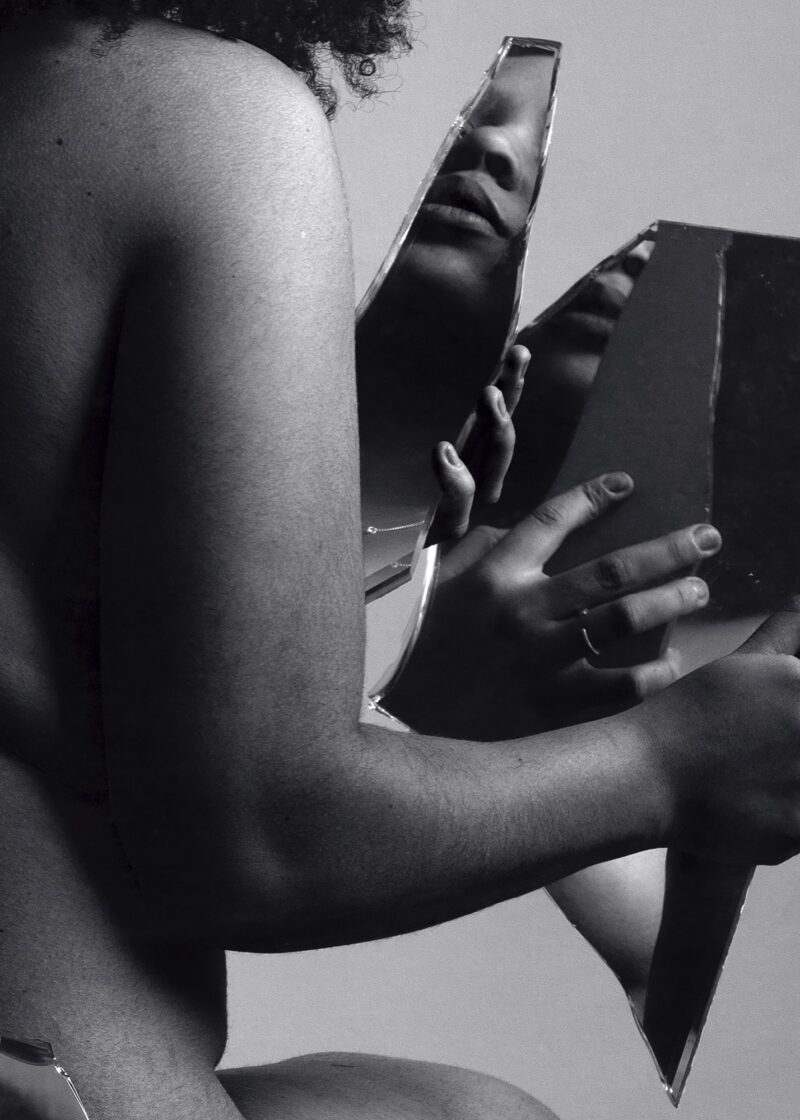

Self-portraits, like pieces of a puzzle, are prominent; one of these is a double-page spread presenting fragments of a nude body, reflected in pieces of mirror, in the centre of which is inserted a booklet with alternating quotations and views of the house in Bafoutam in which the ochre of the earth and buildings, the green of the vegetation, and the beauty of the dusk light stand out. Farther on, two black pages have cut-outs that “frame” images of body parts in contact with the elements (earth and water) speaking of the “(dis)embodiment” of the “diasporic body,” – a direct echo of the title, Architecture of the Self.

She also reveals herself through the materiality of her family’s photographic archives: portraits taken in the studio or during festive moments testify to a past that she did not directly experience but has appropriated. For her, these are much more than images: they are living objects that unearth buried emotions. She takes inspiration from the Black feminist theorist Tina Campt,4 who proposes an interpretation of illustrations as objects to feel and listen to. Playing on the photographs’ emotions and haptic dimension, Lowe Mpoka invites us to resonate with her work, to experience the images beyond simply viewing them. Two QR codes allow us to “see” the songs she recorded: those of her grandmother, whose hands alone (intertwined with her own) are filmed, and the family’s children singing the Cameroonian national anthem.

By reassembling the pieces of the family mythology and integrating fragments of herself into it, Lowe Mpoka offers a sincere introspective voyage, in a book “rooted” in Montreal, made and published by Les éditions Pièce jointe,5 with the support of the Centre d’art et de diffusion CLARK. Translated by Käthe Roth.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 129 – FROM CONTINENT TO CONTINENT ]

[ Complete article in digital version available here: Mallory Lowe Mpoka, Architecture of the Self]

A graduate of Concordia University, Mallory Lowe Mpoka centres her practice around photography, textiles, and ceramics, through which she addresses themes such as migration, self-perception, and environmental colonialism. Among the honours she has received is the Prix Malick Sidibé, awarded at the Rencontres de Bamako – Biennale africaine de la photographie, in 2022. She was a finalist for the 2022–23 Access ART x Prize and has received the RBC Future Launch Scholarship. Her work has been exhibited in Canada and internationally.

lowemallory.com/

Érika Nimis is a photographer, historian of Africa, and associate professor in the Art History Department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa, including one adapted from the doctoral dissertation, Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba (Paris: Karthala, 2005). She contributes to various magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.

1 The work was presented at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, in the group exhibition Light: Visionary Perspectives, July 13, 2024–April 21, 2025, agakhanmuseum.org/whats-on/light-visionary-perspectives/.

2 Mallory Lowe Mpoka, Architecture of the Self (Montreal: Pièce jointe éditions and Centre d’art et de diffusion CLARK, 2024).

3 The Bamileke people were brutally massacred as they fought for their independence (from France) from the 1950s to the 1970s.

4 Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

5 Run by a curious and generous duo with a high-quality approach to contemporary art creation, Pièce jointe works in close collaboration with artists to offer publications that are accessible, beautiful, and eco-responsible.