[Fall 2024]

Maxence Croteau, L’infime (codex)

by Michel Hardy-Vallée

Maxence Croteau, L’infime (codex), 2023, exemplaire unique, 802 pages

[EXCERPT]

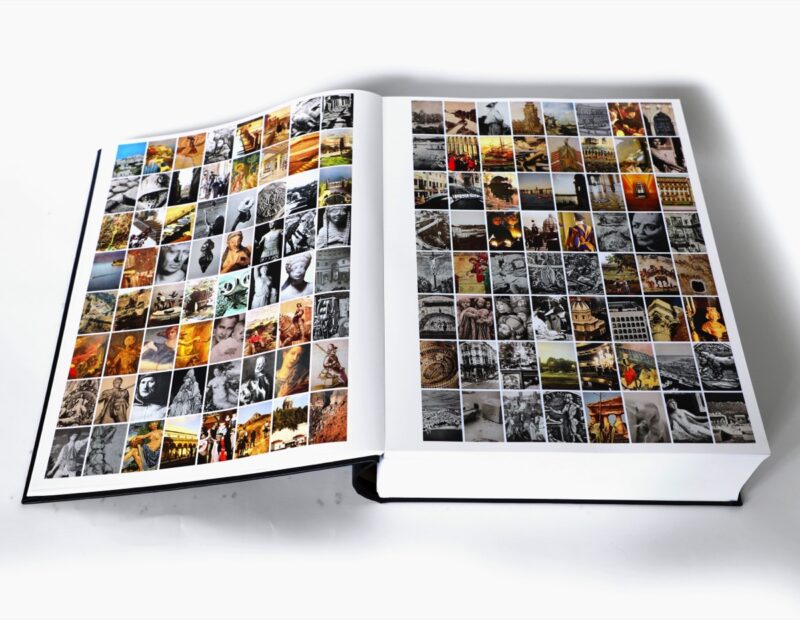

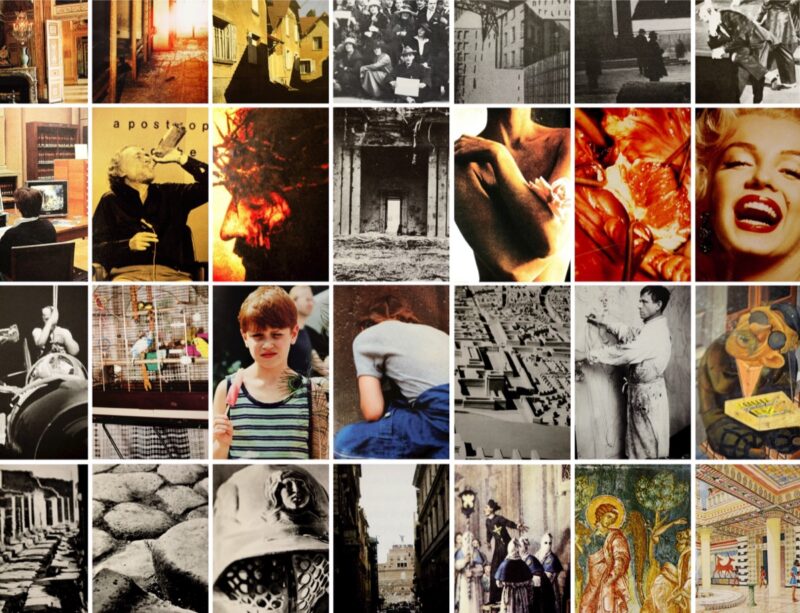

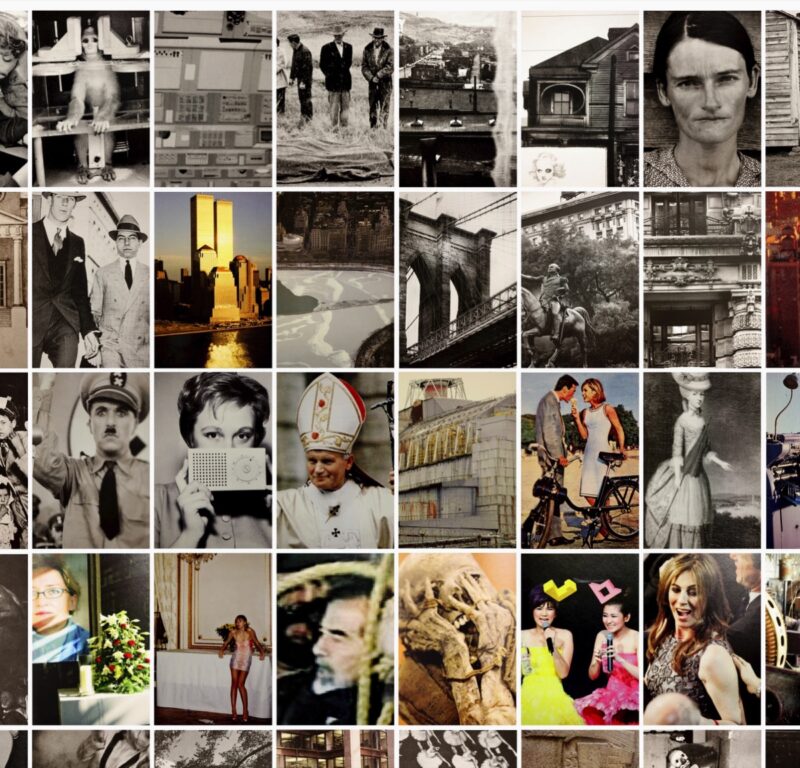

In a way, a library is a form of conceptual art: uniform layout, complex and rational organizational system, comprehensiveness, and seriality. Each book in it is displayed as a ready-made. It nevertheless communicates an organic, physical, and emotional experience. I remember how sad I was, during the pandemic, to see the shelves of the Grande Bibliothèque, wrapped in sanitary plastic, turned into an accidental Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Maxence Croteau’s work would have been a welcome antidote. In the UQAM arts library, he took each volume off the shelves, flipped through it randomly until he came across an image that caught his eye, and took a photograph of the interesting detail; then he began again, until he had gone through every shelf. The images were then arranged on an inflexible grid reproducing the sequence of classification numbers and printed to compose a huge perfect-bound hard-cover codex. Exhibited at Galerie Laroche/Joncas, the document was accompanied by a mural composed of full double pages and isolated images printed on rigid supports. In Croteau’s system, nothing is very complicated. L’infime (codex) follows in the footsteps of classic conceptualism, whether it’s Melvin Charney’s The Main … Montréal (1965) or Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) – that is, a work that tries to strip away the hierarchy of the gaze through exhaustivity: Each Monograph on the Shelves of the UQAM Arts Library would have been an acceptable alternate title.

The choice to reproduce the images from art books places Croteau’s work in the domain of infinite semiosis: each image is part of another image, which itself refers to something else, and so on. Intellectually, it is almost impossible not to connect the book to every possible art philosopher, theoretician, and hypothesizer – Plato, Umberto Eco, Gilles Deleuze, Jorge Luis Borges, James Joyce, and infinite others – because, in theory, everyone who informs Croteau’s work is already a part of it. When I read the master’s thesis that underlay this creation, I noted the sometimes-monotonous catalogue of academic references. But overall, Croteau’s work is not a one-to-one-scaled mapping of the library, of art history, or of Quebec culture. Its limitations are human: those of an artist who has only finite energy to devote to his project, or of the viewer who will inevitably find some of the images familiar. For me, it was a revelation to realize that I recognized some Quebec photographers at a glance from fragments of their images (two Hassidic Jews by Edward Hillel and Raymonde April’s self-portraits, for example).

I found the materiality of Croteau’s approach more interesting than his system. After all, we live in a time when eating every item on a fast-food-chain restaurant’s menu is a legitimate form of public entertainment on YouTube. In his thesis, Croteau evocatively described how the project wore on his body and explained his attention economy, his mental exhaustion, and the subtle alterations to the binding or the pages of a book that drew him to consult them. Such discomforts are also those of librarians. Each system is an attempt to master something (an object or oneself) and, although one can analyze in depth and breadth the subtleties of a concept (what it includes, what it excludes), its concrete application is more significant. With apologies to the Sherrie Levines, refuting originality does not invalidate the value of creation. Artists make not new images but new actions.

The exhibition layout of L’infime (codex) offered two different forms of access to its performance: the book as monument and the pages covering the walls like wallpaper. Although the book contains a totality, the fact that it’s impossible to view more than two pages at a time limits its panoptic ambition. Nevertheless, the wall arrangement engendered a narrative effect, and each image seemed to be the poignant portrait of a dear departed in a memorial, such as those that come together spontaneously after tragedies or those that are more permanent, like Maya Lin’s. Walking through rows of bookshelves is an exhilarating moment in the day of a library rat – a cinematic moment that combines excitement about the title to find with the vertigo of standing before an abyss of potential knowledge glimpsed. It seemed to me that the deployment of Croteau’s entire work in the space would give it a human scope that his weighty codex does not completely achieve. Translated by Käthe Roth

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: Maxence Croteau, L’infime (codex) – Michel Hardy-Vallée]