[Fall 2024]

For “Better and Freer Tomorrows”

by Claudia Polledri

[EXCERPT]

I am shocked at the fate that the Almighty has reserved for the Kurds. These Kurds who, by the sword, so often conquered glory, are now only to find themselves deprived of empire and dominated by their neighbours?

– Ahmedê Khanî, Mem and Zîn, Kurdish epic written in 1692

Behind their apparent “obviousness,” Zaynê Akyol’s photographs contain a world. They link the present to the past of a nation that is still without a state and extends into four countries (Türkiye, Syria, Iraq, and Iran), and they question the future, ever more uncertain, of the region. These images also connect two similar yet distinct media: film and photography. The former is Akyol’s main artistic terrain. Her career as a filmmaker includes two documentaries that show, unstintingly, the military and political issues facing the Kurdish armed forces, especially after the advent of the Islamic State (IS) in 2014. In Gulîstan, Land of Roses (2016), Akyol documents her encounter with the female fighters of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), whom she spent time with in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan before they left for the battle of Sinjar (2014–15). During the shooting of this film, in which the women’s faces are the protagonists and the weapons have names, the idea of turning to photography arose, which led her to produce the project Rojekê, One Day (2016).

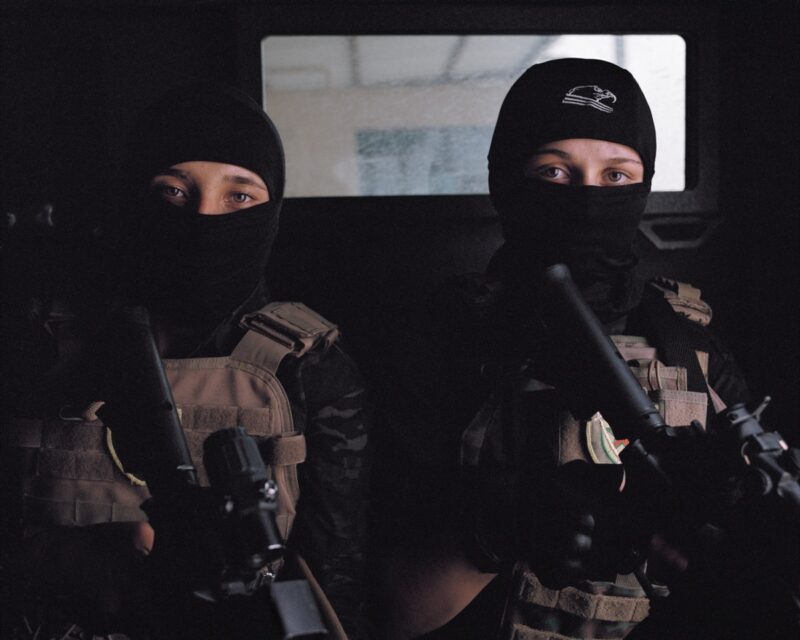

The photographs presented here, under the title NÛJEN, les combattantes, are taken from Akyol’s second feature-length film, Rojek (2022).1 Shot in Syria, Rojek presents a series of interviews with ex-IS fighters now held in prisons controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Some of the people featured in the photographs appear in a sequence in the film. We see them preparing to leave for Hajin in order to “save Deir ez-Zor” from Daesh – Deir ez-Zor being both a city and a governorate situated in northeast Syria on the Iraqi border, at the intersection of roads leading to Raqqa (to the northwest); Mosul, Iraq; and Palmyra (to the southwest), and a strategic crossroads for IS. It is precisely to these Syrian territories, between Deir ez-Zor and the cities of Raqqa and Aïn Issa (in Rojava, or western Kurdistan) that Akyol’s images take us.

In Gulîstan, Land of Roses, women enlist in the PKK army; those in the photographs, whether they are Kurds, Arabs, or Assyrians, are part of the Women’s Defence Units (YPJ, formed 2013) or the People’s Defence Units (YPG, formed 2011), created to fight against the Syrian regime. Since the battle of Kobani (2014–15), both have been on the front lines in the fight against IS. These units constitute the armed branch of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party, in Syria, and are part of the SDF coalition.

This military cartography is far from insignificant; it explains why these images are not simply pictures of “female fighters” but reflect a composite geopolitical universe into which Akyol found her way not solely thanks to her Kurdish origins. These pictures, like the film, are the result of a challenging process – both beforehand, what with authorizations, permits, and waiting, and in the field, due to the wartime context. In fact, it was the difficulties of directing a film crew under such circumstances that impelled her toward photography, which enabled her to establish a more direct relationship with the image and with the subjects portrayed. Finally, these photographs form a record of her encounter with these women, with whom she bonded during weeks of sharing and conversation as the film was being made.

Compared to the more intimate portraits in Gulîstan, Land of Roses, in the series NÛJEN there is a clearer connection between the female fighters and the land in highly symbolic sites. For this series, Akyol used a medium-format analogue camera, known to produce high-quality portraits and accurate colorimetry. Many of these images were taken in the Syrian city of Raqqa, an IS stronghold that the SDF, led by Kurdish commandant Rojda Felat, had liberated on October 17, 2017. Produced two years after the fall of the caliphate, NÛJEN exposes, through the women’s poses (not directed by Akyol), their sense of power over this place, though devoid of any ostentation or triumphalism. The two photographs taken of fighters in front of and inside the national hospital – with the stadium, the last building liberated by the SDF – evince a notable lack of arrogance, as if their presence there was enough on its own to demonstrate their valour. Most often, the women stand in front of ruined buildings, a metaphor for those who resisted, contributing to the collapse of the caliphate.

The soldiers’ determination emerges more in shots such as those taken in Deir ez-Zor. In one of them, the women’s faces and gazes show no hesitation, and their confidence is manifested in their V formation – a figure both balanced and expressive, reinforced by the framing. The smiles and pauses in some pictures help to mitigate any sense of intimidation. Their obvious familiarity with the weapons, which seem to be extensions of their bodies, paradoxically accentuates an effect of “normalcy.” However, the photographs of women with their faces covered – the elite members of the YPJ and the YPG, who belong to the Anti-Terror Units (Yekîneyên Antî Teror, YAT) – are in a completely different register. The much more assertive, almost sculptural composition of the bodies in the image taken at Aïn Issa underlines the victory over Daesh: here, they do not stand beside the ruins but on top of them.

Since the war with IS broke out, in 2014, the Kurdish women fighters have often made headlines, notably in the Western press, but their commitment to different Kurdish armed groups goes much further.2 The terms often used to describe them range from “heroine” to “victim” to “terrorist” – stereotypes reinforced by images that, by dwelling on their feminine features, evoke one or another of these descriptors. Akyol’s photographs, on the other hand, offer a different view of these women, built from within, with no spectacularization or roles or genders. They reproduce, with apparent simplicity, a difficult reality, and they avoid the pitfalls that the scopic drive related to photography may sometimes provoke.

Placed in relation to the film Rojek, the photographs in NÛJEN acquire greater depth of field, allowing us to better understand the motivations that led these women to engage, as well as the murderous ideology that they are confronting. The counterpoint between these two works is no doubt one of the important aspects of Akyol’s approach. It remains that these women fighters never cease to challenge us, as they deconstruct roles and redefine stereotypes such as the one that associates war with the male sex. As Leila, an experienced fighter, reminds us, “We mustn’t forget that it is not women who make violence, it’s ‘war’ that is violent.”3

Finally, we are reminded that in the Kurdish language the words jin and jiyan – “woman” and “life” – share the same root. These words, along with azady (freedom), have long been a slogan4 of the PKK, in which the role of women and the struggle against the patriarchy have been largely conceived, thematized, and asserted. Does this hymn to women and life contradict warlike postures in constant dialogue with death? What comes to mind is what Sozdar Cudî says in one of the final scenes of Gulîstan, Land of Roses before she leaves on a mission – words that might also have been spoken by the women photographed for NÛJEN: “Tomorrow . . . We’re going to war. You’re coming too. I hope it will be a successful fight and that we save our Arab people over there. At this moment, my words might be my last words for you or they might not. Either way, I’d like my video journal to be yours, to be yours as a souvenir. I hope that we’ll live better and freer tomorrows. . . . In those free days to come, with a free life, with a free art, I’d like to see you again.” May these words and these images continue to speak to us. Translated by Käthe Roth

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 127 – SISTERS, FIGHTERS, QUEENS ] [ Complete article in digital version available here: For “Better and Freer Tomorrows”]

Notes

- 1 The film was chosen to represent Canada in the Best International Feature Film category at the 2024 Academy Awards.

- 2 The period varies by region of Kurdistan and by armed group: between 1979 and 1981 in Iran, in 1990 in the PKK, in 1996 in the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, to cite just some examples.

- 3 Quoted in Somayeh Rostampour, “Front de guerre. Un temps pour la transgression de genre en Turquie ?,” Les Cahiers du CEDREF 24 (2020): 69–89, https://journals.openedition.org/cedref/1321.

- 4 The slogan “Woman, life, freedom,” taken up during the funeral of Masha Jina Amini in Saqqez in Iranian Kurdistan (September 17, 2022), gave voice to the uprisings that followed until 2023 and that the Kurds called the “Jina revolution.”

The artist

A graduate of the Media School at UQAM, after earning her bachelor’s degree Zaynê Akyol won the René Malo Chair award for most promising documentary filmmaker for her medium-length film Iki bulut arasind/Under Two Skies (2010). Since completing her master’s degree with a focus on relational and creative issues in documentary film, Akyol has made two feature-length films, Gulîstan, Land of Roses (2016) and Rojek (2022). She has received many distinctions, including the best feature film award at the Milan Film Festival in 2016 (for Gulîstan, Land of Roses) and the special jury prize at the Toronto Hot Docs Festival in 2022 (for Rojek).

realisatrices-equitables.com/dames-des-vues/realisatrice/zayne-akyol/

L’autrice

Claudia Polledri is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Université de Montréal, where she earned a doctorate in comparative literature devoted to photographic representations of Beirut (1982–2011). An expert in Middle Eastern contemporary photography, she was curator of the exhibition Iran. Poésies visuelles, presented in Quebec in 2019.