For over twenty years, Kim Waldron has pursued an enterprising art practice in which she explores modes of self-representation to inscribe herself in such social spheres as family life, various inflections of labour, representative politics, and corporate finance. To this end, she develops durational projects that allow her to assume diverse roles in real-life contexts. The body of work presented in Kim Waldron ltée: société civile1 bears witness to these experiments and the issues they address. Moreover, the notion of socially embedded self-representation at the core of her artistic inquiry is eloquently foregrounded in the exhibition design and conceptual approach. This tour de force is both a revealing panorama of her multifaceted practice and a fascinating (self-)reflection on artistic production and the curatorial process behind the exhibition.

The video

Self-portrait (2017), the exhibition’s opening work, sets the tone for this overview of a practice that is always interwoven into the social fields within which it unfolds. Against a background of steel-and-glass high-rises viewed from a certain height, a vague, diaphanous figure is slowly reflected against a windowpane. As the image gains definition, it becomes evident that its stealthy presence portrays Waldron in an office space facing the buildings in the background. Her ethereal presence in the midst of the impersonal corporate towers points to the opposite poles in which her self-representations unfold. Her barely visible appearance, at one end, and the imperious towers as a symbol of a faceless society, at the other end, define the field within which intimate experience encounters broader social forces.

This initial situating of a border between self and society is brought into clearer focus in a small display chamber at the centre front of the large gallery. The images shown here pertain to Waldron’s more personal sphere. In addition to the aforementioned Self-Portrait, three paintings of a pregnant Waldron and two photographs from the Kim Kim series (2008), portraying both her real family and a fictional adoptive Korean one, are mounted on the chamber’s exterior walls. Considered as a group, these images evoke a sphere of personal identity and immediate family belonging. This sense of a threshold to intimacy is further underscored by Big Mac and Patty (after Martha Wilson, Breast Form Permutated, 1972) (2023), a grid of nine photographs that is the sole work displayed inside the chamber. This deeply personal work bears witness to the treatment that Waldron underwent for breast cancer. This courageous expression of vulnerability evokes an experience at the limit of the representable. Like a core, this sensitive interiority is enveloped in an outer layer of representations of self-identity and family belonging. It is in relation to this initial boundary that the interplay between the fictional and real, the individual and collective, is set into motion. In order to create dialogue across these registers, the curators made the crucial decision to break up the series form in which most of Waldron’s work had been previously presented.

Using the primarily photographic corpus as a sort of reservoir, they organized individual works on the basis of shared characteristics, such as common themes, similar gestures or situations, and recurring pictorial elements. The resulting wall groupings, composed almost exclusively of photographs depicting Waldron in a range of social situations, are mounted along the walls of the gallery’s two main rooms. The busy display creates a dizzying impression of a presence that oscillates between singular and multiple and cuts across various timeframes. This combination of recurrence and change is judiciously highlighted in the selection and display of the photographic arrangements.

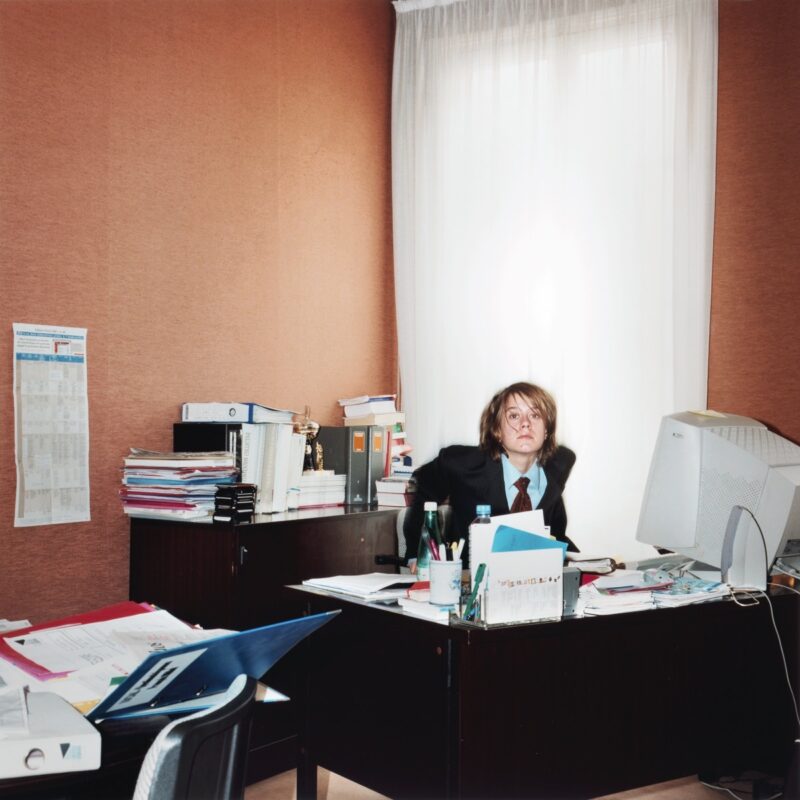

On one of the wall spaces, the photographs’ common denominator is that they contain pictorial elements linked to reading or instruction. The images show Waldron reclining in settings with bookshelves behind her, consulting printed documents in a library, sitting at a desk looking at a computer screens, and so on. These works are drawn from the series Working Assumption (2010), in which Waldron depicted herself in various professional roles; Made in Québec (2015), a project based on exporting her labour to China as a way to question the cheap labour that makes Western consumption affordable; and No Hero (2022), a series centred on the potential role that individuals can assume in a collective endeavour to combat climate change. In another grouping, the notion of labour emerges as the unifying thread. Photographs show Waldron in a white lab coat or wearing grey Chinese workwear as she carries out manual tasks in industrial settings. Many of these images were also drawn from No Hero and Made in Québec.

Another image cluster shows her in situations that involve the preparation or consumption of food drawn from series such as Beautiful Creatures (2013), a project in which she gained firsthand experience of the slaughtering and butchering processes involved in meat production, and Triples (2009), in which she took on the role of a third person in couples’ domestic sphere. Images of social situations related to maternity, family, and friends are gathered in yet another group that also cuts across several series. In addition, the groupings are mounted according to a timeline in which the earliest works are placed at the top and the most recent at the bottom, thus underscoring the return of common themes. However, it must be noted that two of the project’s more politically inflected series are not jumbled up in the same manner.

Both of these projects examined the political ramifications of self-representation and signalled Waldron’s increasing engagement at the time. The first, Same Day (2012), here shown in its entirety, comprises a succession of framed front pages of Canadian newspapers published on the same day, on two separate dates. The selected headlines revealed a clear media bias in the coverage of the 2012 Quebec student strike. The series is completed by two other documents: an original letter that Waldron wrote to then Prime Minister Jean Charest to denounce his response to the strike, and, alongside it, a highly edited version of the same letter published in the Montreal Gazette. These last two works are juxtaposed with the campaign poster that she created as part the Public Office (2015) project, which revolved around her running as an independent candidate for the 2015 federal election in the Papineau riding. The poster features the inscription Indépendante printed above a photograph of her striking a proud pose with a prominent pregnant belly. She thus mobilized her self-representation as a means to question the ramifications of delegated political representations, particularly with regard to gender equity and generational inclusivity.

These ensembles testify to Waldron’s incursions into the political sphere, while also paving the way for a more conceptually informed approach to self-representation that followed in their wake. In particular, this involved a shift from image-based to document-mediated self-representation. This transition is brought to light in the cubicle at the end of the exhibition itinerary. In contrast with the two main gallery rooms, which are abundantly peopled with images of Waldron, there is hardly any presence of her visual likeness in this much smaller space. Instead of the photographic image as an identity marker, it is the incorporation and entity of the moral person that is the focus of the series displayed.

This shift was initially signalled with Kim Waldron Ltd. (2016–20), for which Waldron incorporated herself as an offshore company in Hong Kong. The official documents establishing the corporate identity and a photograph of the office tower where the company is registered are displayed on the same wall. By veiling her visibility behind an offshore company, Waldron critiqued the way power is increasingly shifting away from political representation to the sphere of corporate global finance and its identity-evasion stratagems. Moreover, by inscribing “Artwork” as the company’s principal product or service, she drew attention to the invisibilization of artistic labour and critiqued the role of art as a luxury asset. However, since the offshore company served primarily as a haven for a passive income or assets, the company was closed in 2020 for lack for further activity. Its follow-up company, Waldron’s most recent project, Société Kim Waldron ltée (2023), is the primary focus in this cubicle space. Several surprising elements in this final work’s display mode put a significant twist on the exhibition as a whole.

Upon entering the space, one is immediately struck by the presence of a large sheet of paper that covers the entire floor. A reproduction of the EXPRESSION gallery floorplan is printed on this surface. Mounted on the wall, a photograph shows the curatorial team placing miniature photo reproductions of the exhibition’s works on a floorplan exactly like the one beneath one’s feet. This mise-en-abyme representation of the space within the space is complemented by elements that establish Société Kim Waldron ltée’s role in the exhibition process and outcome, such as the company’s certificate of constitution, and an insightful audio recording of a public meeting of its board of directors. More important, however, is the manner in which Société Kim Waldron ltée’s self-referential manoeuvre is itself a development and extension of the practice that it takes stock of here.

Among the stated objectives of this non-commercial joint-stock company that “sells nothing, and offers no services” is the carrying out of an exhibition that now bears the title Kim Waldron ltée: société civile. The survey exhibition is therefore not only a part of Société Kim Waldron ltée, it is the culmination of the company’s activities. Waldron’s many self-representations, her singular embodiments of multiple roles in civil society, are brought together in this survey exhibition that is also a self-representation and artwork in its own right. At once singular, per its namesake, and multiple, per its incorporated status, Société Kim Waldron ltée composes a grand self-portrait from the many strands of Waldron’s multifaceted inscriptions in different social spheres. In revisiting these singular gestures of society made in the multiple images of the self, the company’s activity concretely demonstrates that our actions and ways of being can forge a more just world in which we can better recognize ourselves.