[October 5 2022]

By Julie Martin

A Feminist Avant-Garde. Photographs and Performances of the 1970s from the Verbund Collection, Vienna

Arles, les Rencontres de la photographie

4.06.2022 – 25.09.2022

The exhibition A Feminist Avant-Garde. Photographs and Performances from the 1970s, organized by curator Gabriele Schor and presented at Arles during the 2022 Rencontres de la photographie, features photographs and videos from the collection of the Verbund Foundation, situated in Vienna1. The works, made by women artists in the 1970s, are arranged in five sections: “mothers, wives, and housewives,” “locked-in,” “the dictates of beauty,” “female sexuality,” and “role playing and identity.” Combined, these simple themes demonstrate the extent to which “the personal is political.” This slogan, popular in the 1970s in activist feminist circles in the United States, highlights the fact that the political doesn’t stop at the front door, in the family, in the couple, or in intimate relationships. Problems experienced as isolated within the private sphere are actually systemic and symptomatic of collective oppression. “The personal is political”2 thus summarizes the main claims of second-wave feminism, which, unlike the first wave, which was concerned with voting rights, demanded relative emancipation of the body, sexuality, and daily life.

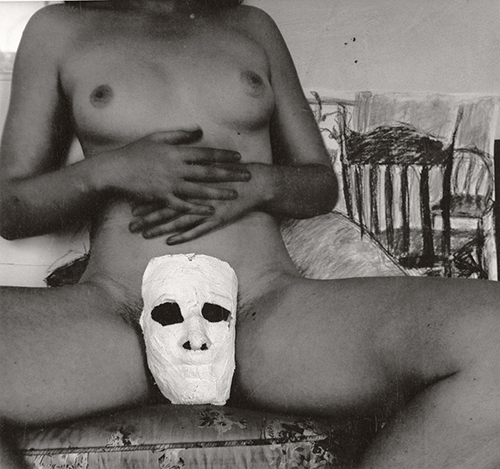

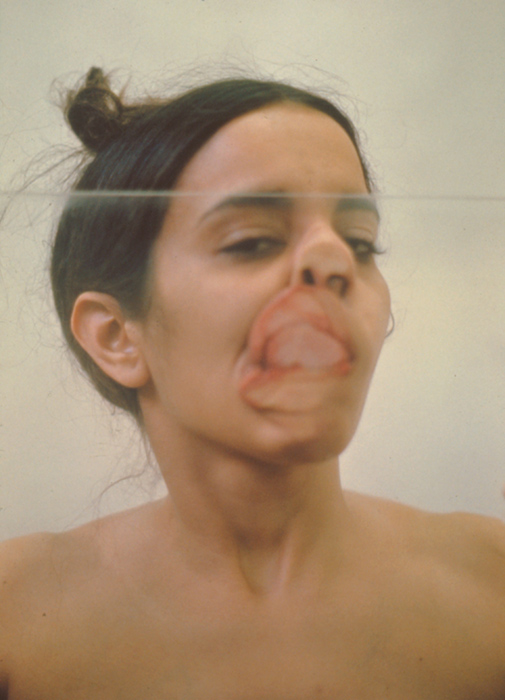

Such concerns were prominent in the work of numerous women artists during the 1970s. Their artistic approaches involved the female body – their own – which they staged within the domestic space through alienating everyday activities, whether they dressed it in stereotypical garb, mangled it, or smothered it. Because the body was where domination was exercised, it was also where the critique of domination was carried out. In parallel, performance art, which developed in the West in the 1970s and placed the artist’s body at the centre of creation, was of particular interest to feminist movements, as it was a new art practice that had not yet been imbued with a long history of patriarchal art and the figure of the male genius, as painting and sculpture were.

Because they were ephemeral, the performers’ actions were often captured on cameras and preserved in still or moving images. The use of video, like performance itself, was still new, and therefore women had not suffered long, passive exclusion from it. The quickness and simplicity of production also seemed to respond to the urgent need for expression.

The exhibition continues the exploration of visibilities in the social and art field by including works by well-known artists, such as those from the United States (Dara Birnbaum, Judy Chicago, and Carolee Schneemann, for example) and bringing to light those by artists who are not as easily identified. Above all, the exhibition layout underlines the existence of similar gestures emerging in different geographic, political, and cultural contexts, exposing a common condition of subjection and an identical desire to escape it. The eight photographs by Renate Eisenegger titled Isolamento show the progressive obstruction of her mouth, nose, ears, and eyes, until all possibility of expression is blocked. The bound faces in the works by Annegret Soltau and by Sonja Andrade evoke a similarly fettered life. Playing on dress codes to demonstrate the constructed dimension of the female identity is key to the photographs by Cindy Sherman, as well as those of Martha Wilson and Marcella Campagnano.

Nevertheless, feminist art is far from homogeneous and free of internal controversies. In the 1970s, white feminism was criticized for seeming to ignore other systems of oppression, including those related to class and race. Theoretician bell hooks showed how, under the cover of universalism, the situation of white women overshadowed the specific condition of Black women.3 A Feminist Avant-Garde takes care to bring to the public eye the work of racialized artists who, through their works, have testified to their particular position at the intersection of several kinds of oppression. In her grating video called Free, white and 21, Howardena Pindell recounts the racist assaults that she and her mother have experienced. Her interlocutor, disguised as a white woman, constantly relativizes the contempt she has suffered and repeatedly recites the terms of the privilege that she enjoys: “Free, white, and 21.” Lorraine O’Grady’s photographs document performances during which she “crashes” vernissages and art events wearing a dress made of white gloves and a sash bearing the words “Miss Black Bourgeois 1955.” Her intention is to call out her fellow artists on how they compromise to conform to the expectations of the white art field.

Far from belonging to a bygone time, the concerns and claims visible in the exhibition are still very current. In 1970, Elizabeth Catlett drew the face of a Black woman whose head is filled with the death of her child. She portrays the perpetual agony of Black mothers whose children are statistically more likely to meet a violent death – a situation denounced today by the Black Lives Matter movement. Although the right to sovereignty over one’s own body is an omnipresent theme in the work of the feminist avant-garde, the revocation of the right to an abortion by the United States Supreme Court confirms that advances are still fragile and regression is always possible.

By choosing to use “avant-garde” as an umbrella term for the practices of women artists of the 1970s, Schor restores their trailblazing role, both artistically and politically. Because the term originates with the military, it lends a combative dimension, buttressing the idea that women artists were not only given to see the feminist movement or puts its demands into cogent form but also were in the front ranks of the battle against the patriarchy. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Many second-wave feminists have used the slogan “the personal is political” in their writings, discourses, and activism. It is often attributed to Carol Hanisch, who wrote an essay, published in 1969, using it as the title. In an essay written in 2006, she explains, “I’d like to clarify for the record that I did nto give the paper its title, ‘The Personal Is Political.” As far as I know, that was done by Notes from the Second Year [in which the article appeared] editors Shulie Firestone and Anne Koedt.” See Carol Hanisch, “‘The Personal Is Political’: The Women’s Liberation Movement Classic with a New Explanatory Introduction,” http://www.carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html.

3 bell hooks, Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (Boston: South End Press, 1984).

Julie Martin is a professor associated with LLA-CRÉATIS (Université Toulouse – Jean Jaurès). She researches documentary art approaches in the era of fluid images and the connections between art and politics. She is the author of “Du médium au média, les pratiques artistiques documentaires face au net,” published in Ligeia Dossiers sur l’art (2020), and, with Sara Alonso Gómez, of “Contre-visualités: tactiques artistiques contemporaines à l’ère des nouveaux médias,” published in Nouveaux médias: mythes et expérimentations dans les arts (2021). She is also an art critic, exhibition curator, and co-director of the exhibition space trois_a (Toulouse).

![Birgit Jürgenssen. Ohne Titel (Selbst mit Fellchen) [Sans titre (Moi avec de la fourrure)], 1974. Avec l’aimable autorisation de Estate Birgit Jürgenssen / Galerie Hubert Winter / Bildrecht / COLLECTION VERBUND, Vienne.](https://cielvariable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/biennales-arles2022-01.jpg)

![VALIE EXPORT. Die Geburtenmadonna [The Birth Madonna], 1976. Courtesy of VALIE EXPORT / Gallery Thaddaeus Ropac / Bildrecht / VERBUND COLLECTION, Vienna.](https://cielvariable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/biennales-arles2022-04.jpg)