[June 2, 2021]

Pierre Dessureault

Presented during the 11th edition of Les Rencontres internationales de la photographie in Carleton-sur-Mer, Gaspé, Unuua (Nuit), a photo-documentary on hunting and the arctic night, was shot by Yoanis Menge in Iqaluit and Pond Inlet, Nunavut, and in Salluit, Nunavik. “In the course of a number of journeys in polar territory,” he wrote in the introduction to the exhibition, “I succeeded in integrating myself into Inuit communities and families with whom I learned to hunt goose, caribou, seal and narwhal. I became friends with certain hunters, who introduced me to rituals and to the ancestral skills anchored in Inuit culture.”[1] His immersive approach of participating in the community’s daily activities is in direct contrast to the position of detached and neutral observer taken by an “objective” documentary maker. A previous project on the seal hunt, Hakapik, produced between 2012 and 2015, resulted from some twenty trips that Menge made as a hunter and full member of the crews of boats based in the Magdalen Islands, Newfoundland, and Nunavut. Hakapik highlighted a first-hand experience and offered an intimate portrait of an activity practised for generations. Menge thus responded to animal-rights groups demanding that the hunt be banned with images both spectacular and controversial.

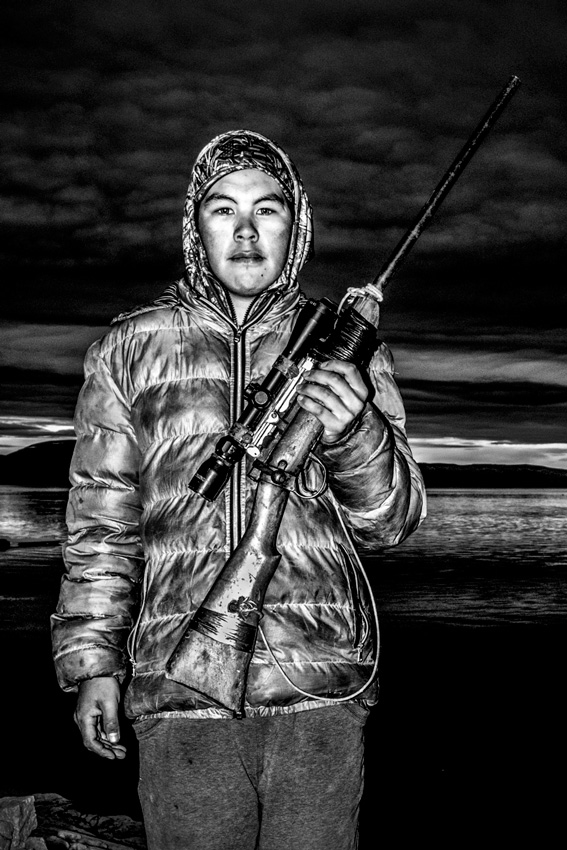

In Unuua, begun in 2013, Menge continues with his approach based on dialogue, flowing from a patient process of learning and discovery – a process instigated by sharing in his subjects’ everyday activities, which reveal the ties binding them to the territory that they inhabit. This familiarity, acquired through privileged access, establishes a closeness between Menge and the local community. It lays the foundation for his knowledge of the people, enabling him to discern their personality traits and identify signs of their material culture. In this sense, his vision is unremitting; his observations, unequivocal. Although hunting was once the cornerstone of Inuit cultures, the manifestations of this age-old activity are fading in favour of practices imported from the South. The latest guns, cell phones, snowmobiles, branded clothing, sedentarization, and dwellings modelled on Southern structures bear witness to the tensions between what some see as progress and others regard as the dispossession of an ancestral way of life, manifested in unique forms of expertise, that had imposed its pace on the community’s activities and made harmonious integration with the Northern environment possible.

Drawing on the qualities of photography as a medium, Menge deploys a visual vocabulary that marks the images with his personality and clearly states his positions and allegiances. The choice of black and white quashes the picturesque and magnifies the details of forms and textures, eliminating the superfluous. By using a flash, he exaggerates the strong contrasts and adds relief to the images, in keeping with the harshness of an environment buffeted between the darkness of the polar winter night and the glare of the midnight sun during a too-brief summer. The almost constant use of a wide-angle lens broadens the field of vision and erases the distance between the photographer and his subjects, who therefore share a foreshortened space. The many close-ups of weathered faces that punctuate the grouping confirm a proximity engendered by life experienced in common.

Menge’s images convey a personal and singular point of view, defining the environment from which the gaze – a composite of perceptions, impressions, believes, and culture –is cast at visible reality. Grafted onto the ethnographic truth of observable facts is the authenticity of the particularized and internalized experience, translated through the photographic medium and the visual language adopted. This fully assumed mediation resulting from an embodied gaze manifests a commitment to the subjects that goes beyond the transparency of factual truth and documentary exactness, which some claim is a gift of the real offered in the moment to the observer.

On the contrary, the image here is the product of meticulous work on visible data, gathered in the field, and of the photographer’s devotion to the lived experience of his subjects. It is an approach that might seem contestable in comparison to traditional documentary practices. “But might it not be a good thing,” writes Pierre Perrault in the essay “Du droit de regarder les autres,”[2] “to contest that approach? To recognize its limitations and look elsewhere for a behaviour that cannot be found here. We learned a great deal in any case, even if the cultural distance seems insurmountable.” Translated by Käthe Roth

Trained at CÉGEP de Matane and then at the Magnum Photos agency in Paris, Yoanis Menge is part of a generation of photographers raised on social documentary, whose authorial position is opposed to that of the photojournalist. Menge, who sees himself as falling into the tradition of direct cinema, works on local issues in isolated communities. He has had exhibitions in Canada and abroad, and his first photobook, Hakapik, was published in 2016. yoanis.squarespace.com

Pierre Dessureault is an expert on Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized more than fifty exhibitions and published books and articles on the subject.

[1] www.photogaspesie.ca/en/portfolio/yoanis-menge-in-carleton-sur-mer/.

[2] Pierre Perrault, De la parole aux actes (Montreal: L’Hexagone, 1985), 303 (our translation).