[Fall 2013]

By Élène Tremblay

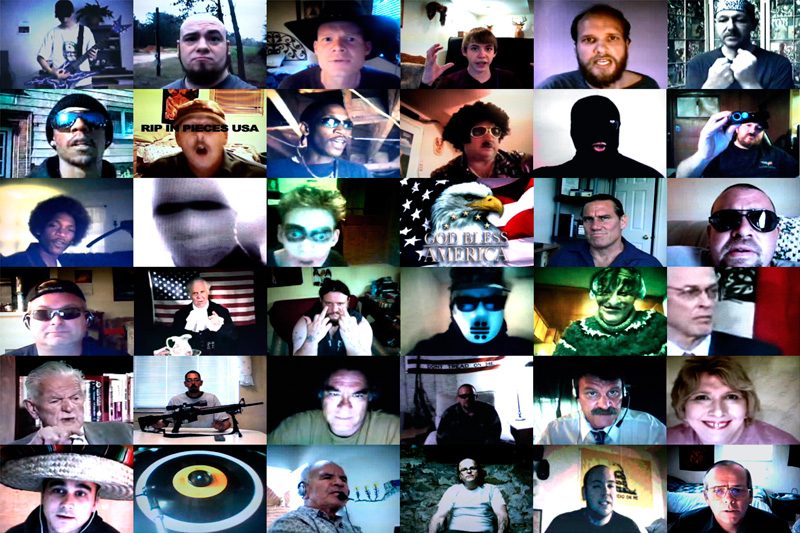

In his Web trilogy – the films RIP in Pieces America, Pieces and Love All to Hell, and Big Kiss Goodnight (2009–13) – Dominic Gagnon finds video excerpts on the Internet, which he describes as a cinémathèque or film archive, and recombines them to produce what he calls “films about people who film themselves.” With this appropriation, he redefines what the found-footage film might become in the Web era, while raising the questions of the artist and of self-exhibition on the Internet.

Without a camera and from a distance, Gagnon adopts the position of hidden observer, anxious witness, and amused nomad – a foreign traveller to the worlds he visits. In an approach that is both postmodern and ethnographic and that bears traces of situationist influence, he captures the paradoxical character of subjects who make spectacles of themselves as they use YouTube to vehemently decry control by the society in which they live.

The diversionary practice that runs through Gagnon’s work, defined for the first time by Guy Debord in 1959, is an approach of critical appropriation of existing discourses in a context of exhibition and generalized spectacle. In Debord’s view, “détournement as negation and prelude”1 aims, through a mirror effect, to show the establishment of the capitalist system as a myth sustained by the powerful image machines of advertising, movies, and television. In his Web trilogy, Gagnon draws our attention to the recent transition from production of advertising images by the capitalist machine to self-production of images by subjects themselves, who deliberately put themselves on display.

Today, YouTube, the new image machine, transforms the present into spectacle, as people digitally archive their gestures and words on its remote servers. A museum of the present, YouTube is a space of “free” exhibition, without the sorting or mediation of museum curators, where everyone’s self-expression is instantaneously published. YouTube’s “performance” archive is deployed organically and exponentially, according to its users’ desires. As a self-publication space, it holds numerous hours of ordinary performances and a few extraordinary moments. In this ocean of banalities, one sometimes finds unique expressions and speeches, and Gagnon, interested in discourses of the margin and resistance, has decided to excavate these through an extensive research project.

For this trilogy, Gagnon’s search by specific keyword (martial law) led him, for a number of months, to follow “survivalists,” “preppers,” and others who feel threatened in the United States. These people perform for the camera alarming, if not incoherent, messages about the various scourges that they think menace American society and how people can protect themselves. Their discourses usually touch on the threat to individual freedoms protected by the second amendment posed by large “conspirationist” corporations and the Obama government, and they advocate, among other things, the use of firearms as a response to these “threats.” Because YouTube encourages its users to denounce verbal abuse and inappropriate statements, these survivalists’ videos are quickly flagged and withdrawn from the service. By discovering this found footage before it disappears and copying it, Gagnon saves it from oblivion – and rightly relabels it “saved footage.”

Because the creators of these videos ceded their rights to YouTube, which threw the videos in the trash, who do the saved copies belong to, the artist wonders. Exploiting legal loopholes and imprecision as well as the celebrity-seeking desire of people who post their performances to the service, Gagnon tests the legal and moral limits of the YouTube apparatus. The saving and presentation of these videos in new contexts not only extends their authors’ desire to be heard but transforms their discourses into ready-mades through the appropriation and displacement gestures typical of postmodern art.

In his Web trilogy, Gagnon draws our attention to the recent transition from production of advertising images by the capitalist machine to self-production of images by subjects, who deliberately put themselves on display.

The immediate exhibition of the self made possible by the webcam and YouTube produces – as Hal Foster describes it in his discussion about the postmodern subject – a subject “suspended between obscene proximity and spectacular separation.”2 The proximity effect of the self-exhibition video on YouTube creates the illusion of a face-to-face relationship with its creator – a viewer before his screen challenged by an individual before his camera. The speech seems to be almost direct, except that Gagnon is inserted between the sender and the receiver to change the trajectory of the message, addressing it to other audiences.

What these survivalists, catastrophists, and preppers expose in turning the webcam on themselves is related to the “abjection” – the projection outside of the self (here through transgressive discourse) – of the threat. These people are made anxious by the fear of seeing their private space and autonomy threatened. The world that they describe as apocalyptic and full of dangers is perhaps not so much external but internal, if we take Julia Kristeva’s definition of abjection.3 All of the warnings, prophecies, and insults gathered in Gagnon’s trilogy try to name the Other, the enemy. They’ve figured that the first 24 hours they gonna have to shoot a lot of us. Prepare for the dollar being worth absolutely nothing, prepare to be hungry, prepare to be scared!4 Soy will raise the level of estrogen in a time where we need men to be men and women to be women. Apathetic sissies!5

Transported by his frantic desire to display himself, Joe, in Big Kiss Goodnight (2013, ongoing), takes to flights of poetry, raises his voice, declaims, becomes theatrical: They’re poisoning the water! I don’t need to have a PH freacking D and an MBA, an AEAA and a TESA, a master’s of this or a master’s of that! Just common sense, people!

This fright and sense of loss of power, felt to various degrees in these times of banking scandals, environmental disasters, and globalization, is excessively, distortedly transposed here into the making of conspirationist myths and a call to take back power with weapons and survival strategies. Look out your door and see that the world is fucked!6 Even a viewer who subscribes to certain aspects of the protagonists’ discourses, such as their criticisms of the power of stock markets and financial interests whose injurious effects are acknowledged by everyone, becomes uncomfortable when these words take an incoherent, racist, and obscurantist turn: If somebody calls you a racist it’s just a word.7 We are made into voyeurs, watching the fascinating spectacle of a disturbed human mind and the twists and turns that it takes with conviction. By collecting, selecting, and bringing together these discourses, Gagnon invites viewers to enter a problematic ethical relationship with this vociferous, expressive, anxious Other.

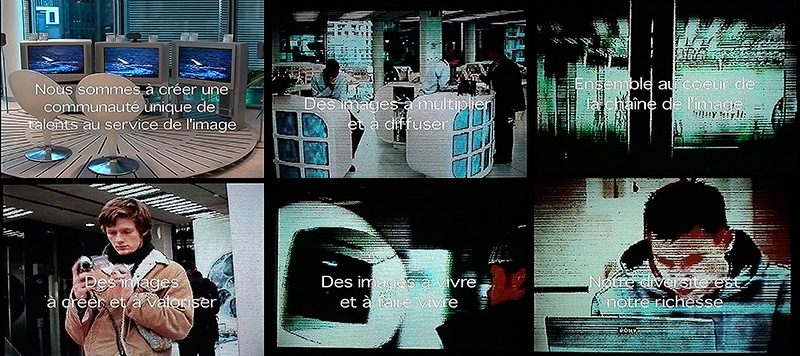

It is important to consider this Web trilogy within Gagnon’s overall approach, which consistently reveals the upsetting nature of this embodiment of the Debordian vision of the society of the spectacle. In The Matrix (2003), he diverted cameras in a Sony showroom in Berlin to film documentary videos of the customers and the store, which he rebroadcast on the monitors on sale in the store and refilmed a number of times until they were completely degraded. His most recent film, Society space (2013),8 diverts and reuses Debord’s film La Société du spectacle; he retains only the sound track, slightly abridged, and adds new, current images – computergenerated, from video games, reality TV, Second Life, and so on – that demonstrate and support all of the acuity and relevance of Debordian theses, which seem to have materialized even more strongly today. “Everything once directly experienced has distanced itself into the performance,” as Debord said.9

The protagonists in this Web trilogy, by turning their webcams on themselves, participate in the very system of panoptic control that they denounce and expose their performance to the view and judgment of everyone. In doing this, they offer themselves up as flesh and material of the spectacular machine and make themselves the heroes of the demagogic stories that they formulate, of which Gagnon becomes the active witness.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Guy Debord, Internationale situationniste, no. 3 (1959), reprinted in Internationale situationniste (Paris: Fayard, 1997), p. 78 (our translation).

2 Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), p. 222.

3 “There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable.” Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), p. 1.

4 Excerpt from RIP in Pieces America.

5 Excerpt from Pieces and Love All to Hell.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Sixty-minute remake of Debord’s film, which was eighty-eight minutes long.

9 Quoted from Debord’s film La Société du spectacle (1973) (our translation).

Élène Tremblay has been an assistant professor in the Department of Art History and Cinema Studies at the Université de Montréal since 2011. She obtained an MFA at Concordia University (1996) and a doctorate from the Université du Québec à Montréal in art studies and practices (2010). In 2013, she publishe L’insistance du regard sur le corps éprouvé, pathos et contre-pathos (Udine, Italy: Éditions Forum).