By Charles Guilbert

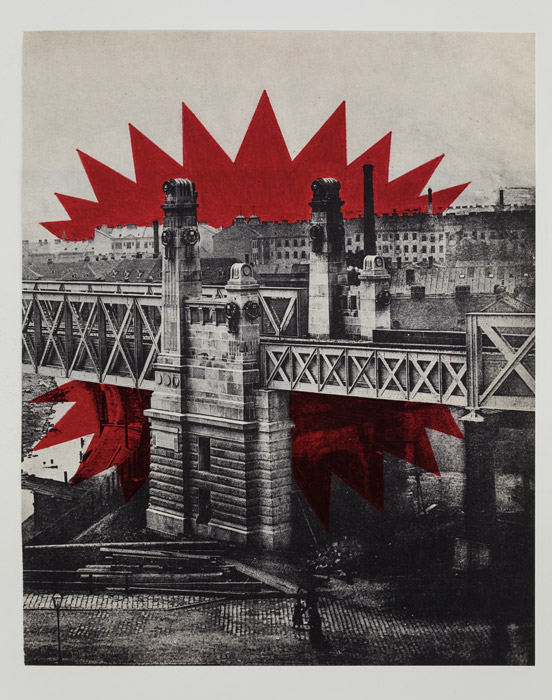

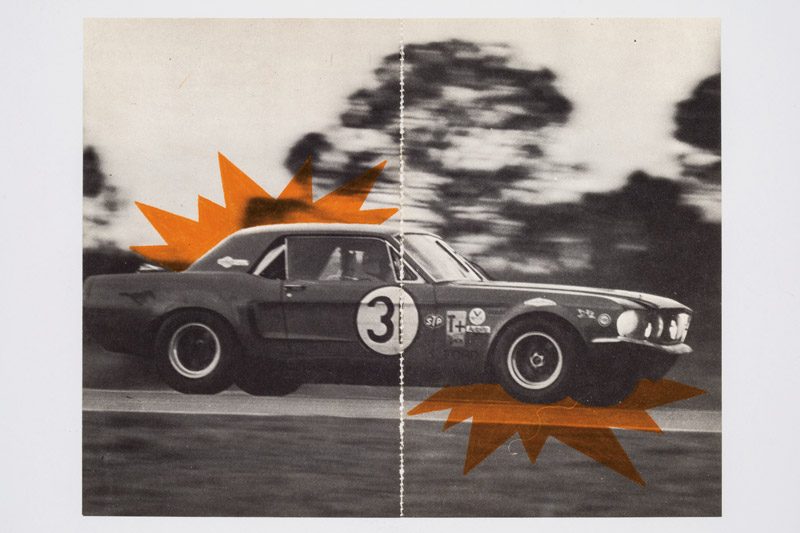

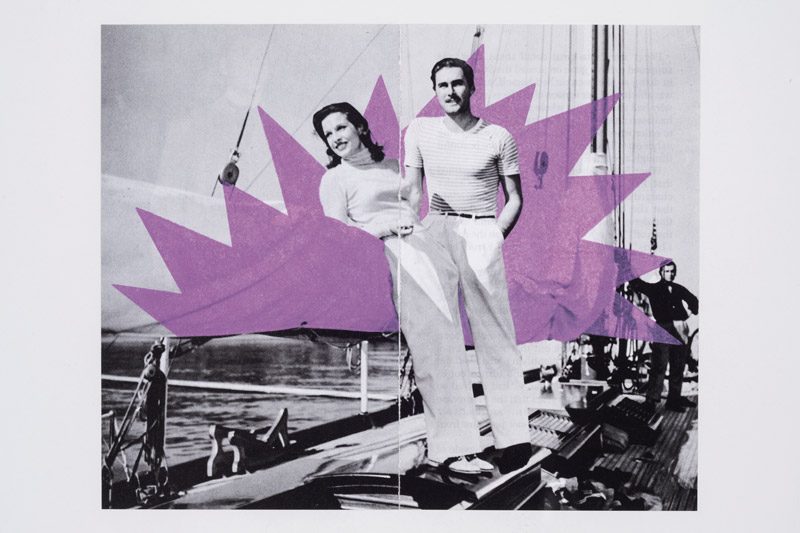

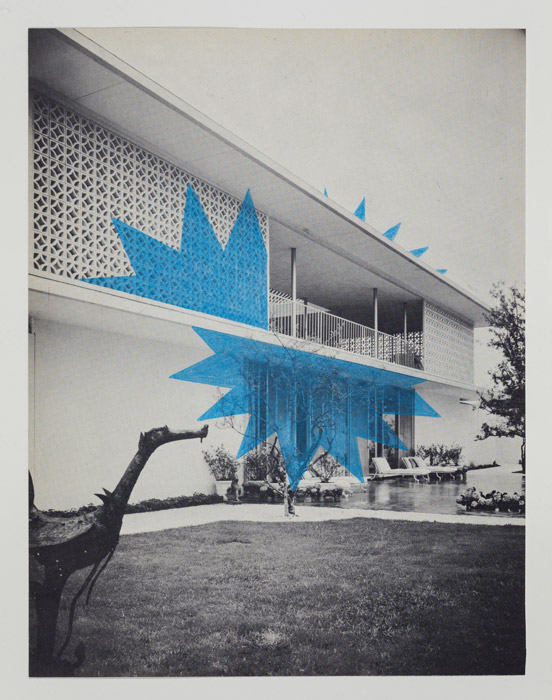

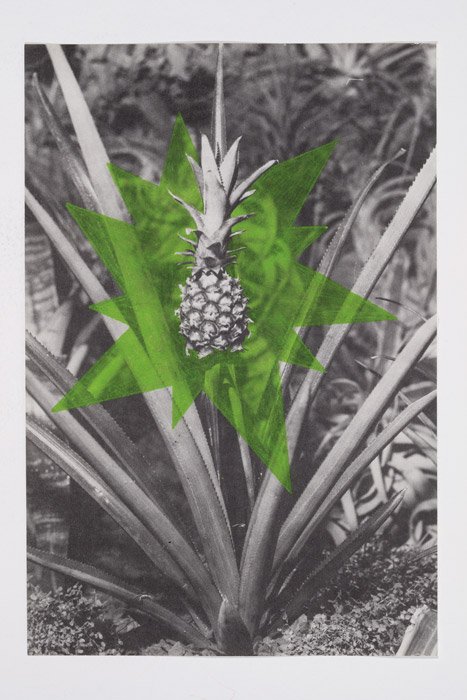

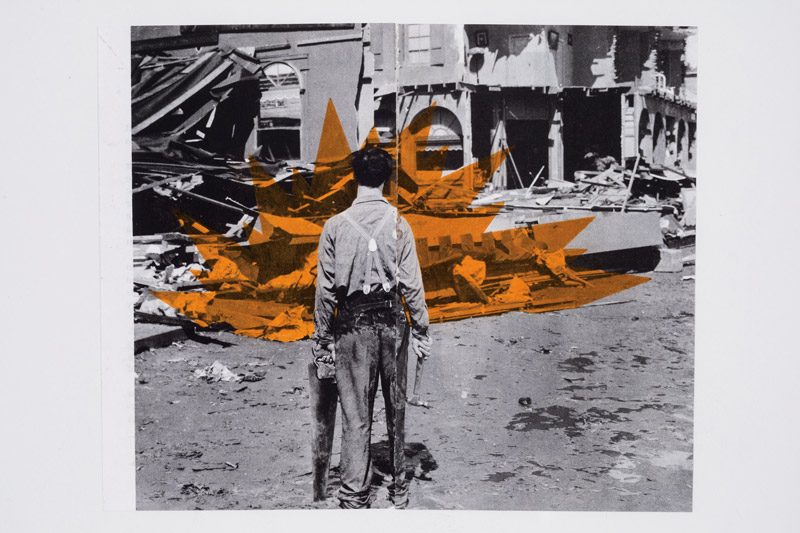

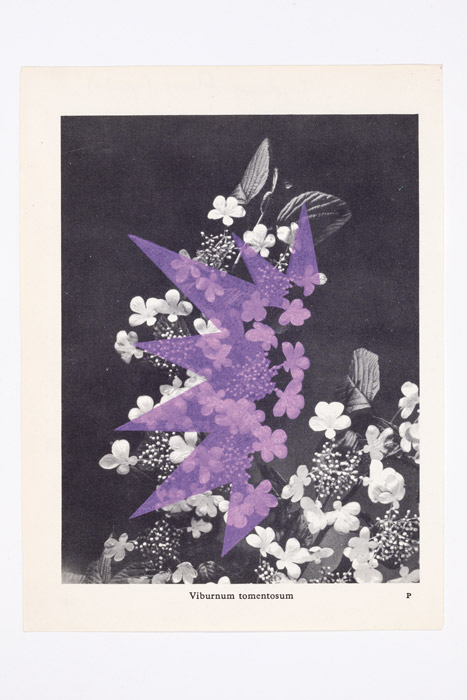

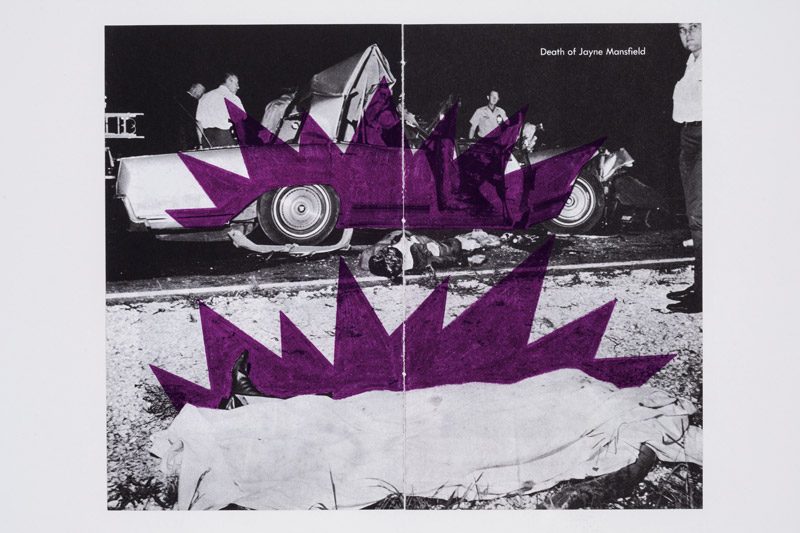

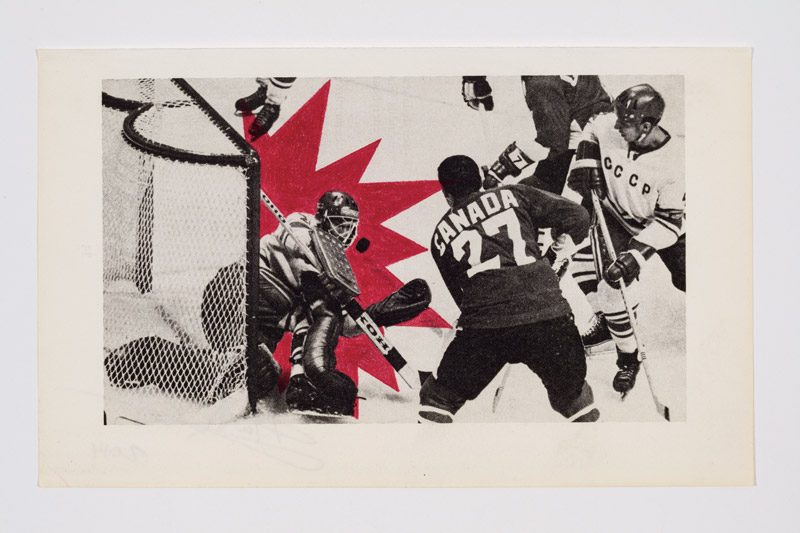

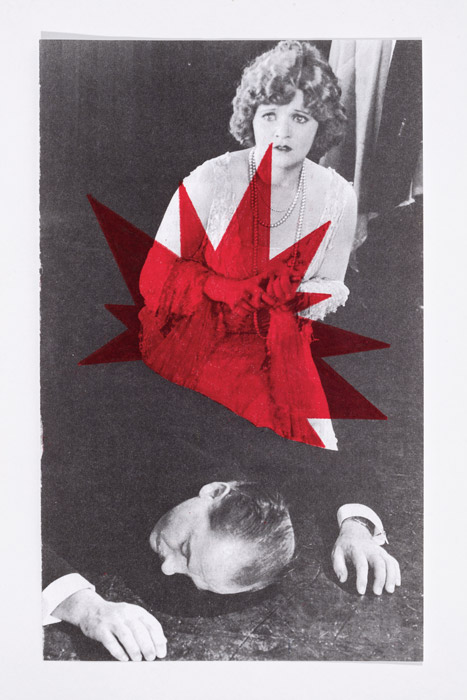

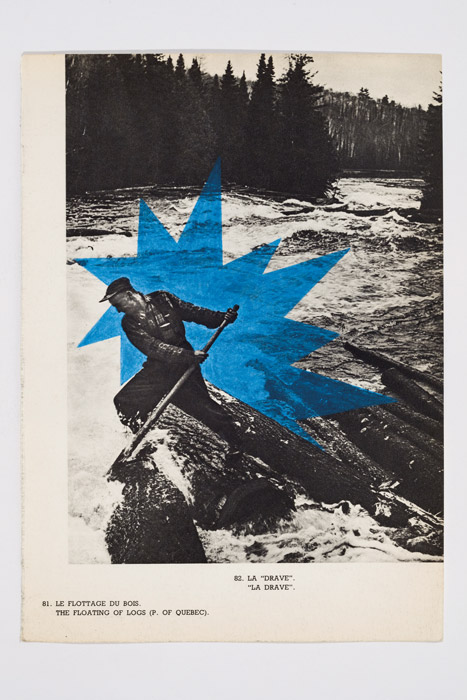

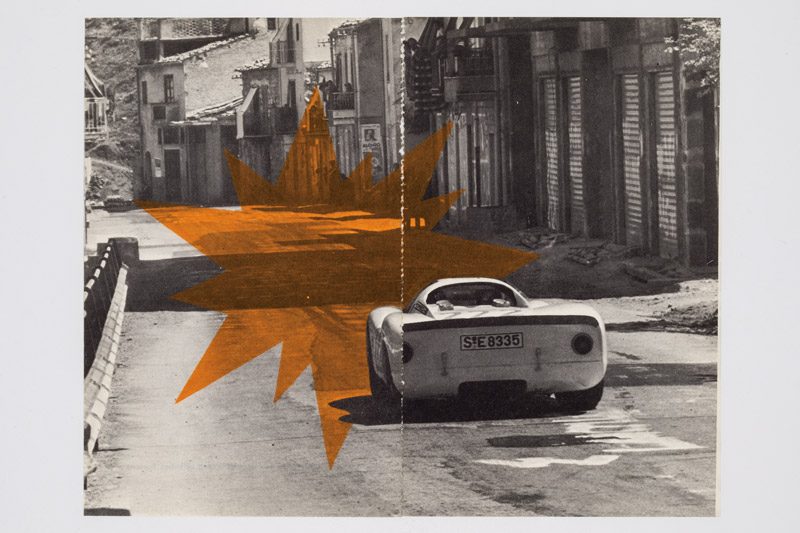

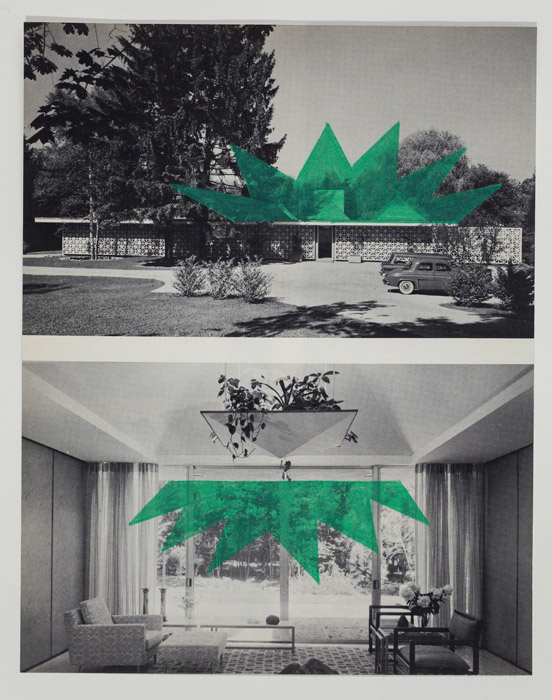

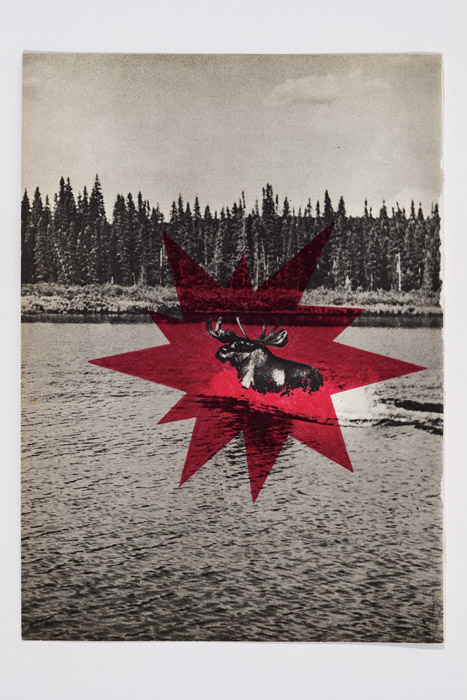

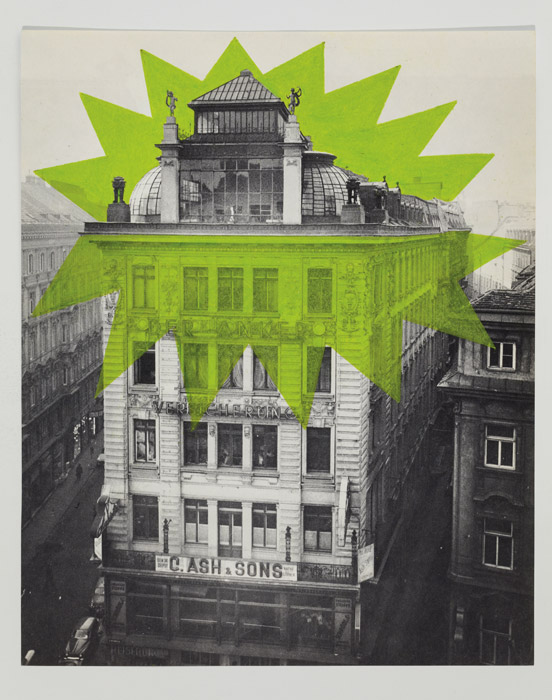

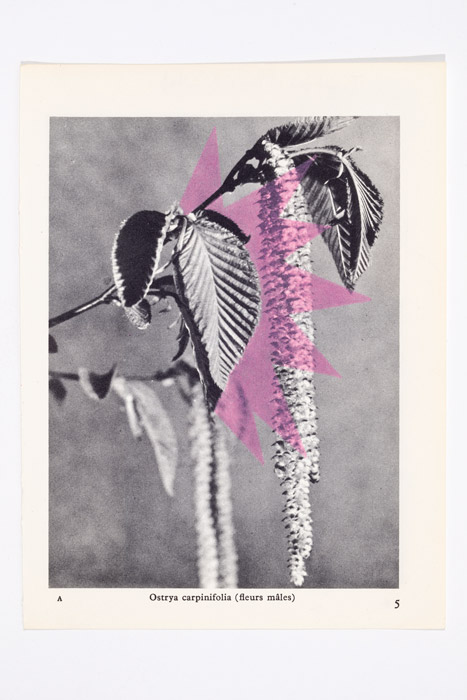

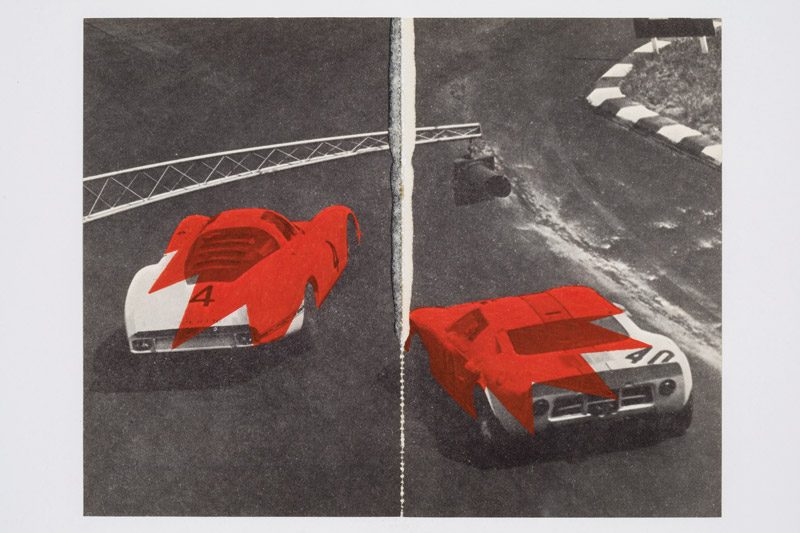

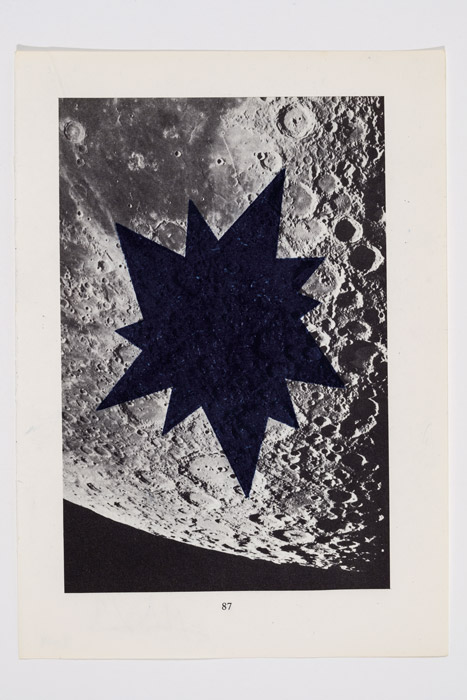

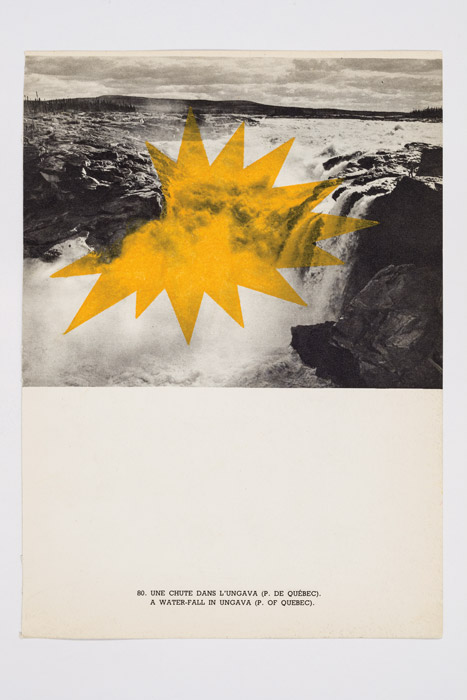

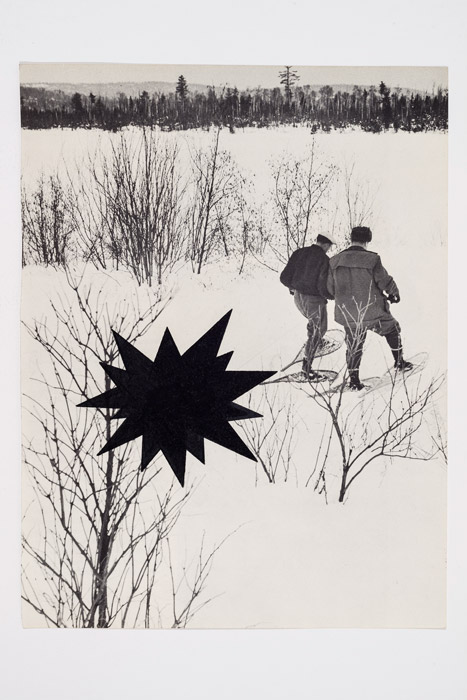

Since 2012, Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf has been working on a series of artworks titled Études préparatoires (dessins d’explosions), which he has presented in various venues and contexts.1 As he has often done in the past, Phaneuf revives found objects by inscribing them in a system of his own making. In this case, it is, quite simply, pages of books presenting photographs on which he has drawn a star-like shape.

Since the beginning of his career, Phaneuf has taken a sarcastic, critical, and sometimes even cynical position with regard to art and the art system, and so we might hesitate for a moment before undertaking a serious critical interpretation of his work. How can we avoid crushing with words the off-handedness of his art? And why should we wear ourselves out seeking in these images a meaning that, we know, will unfailingly end up sinking into absurdity? Perhaps, precisely, to experience this stepping into the breach.

When we closely examine the artist’s progress (progress that, in its systematic and repetitive aspect, may remind us of Sisyphus’s), we see that he problematizes art more carefully than might be obvious at first glance, by making his refusal to resolve the question of meaning a source of creativity. The title “Études préparatoires” (Preparatory Studies), in fact, must be understood on several levels: it is as much an admission of humility (so much remains uncompleted) as a megalomaniacal promise (so much preparation could lead only to a grandiose artwork!). Although ironic, the title nevertheless underlines two important dimensions of Phaneuf’s work: a questioning of what the artist does and a reflection on time.

With an education in art history (and not art), Phaneuf constantly plays on the edge between engagement and distance, art and non-art, painting and document, artwork and prank. Transforming the method that belongs to his field of study (inventories, lists, categorizations) into a creative strategy, he performs an aesthetic analysis of the real world to show its obsessive motifs. His approach, essentially documentary, challenges the traditional idea of the artist’s subjective investment. For Champ de lys, for example, he brought together in a store window a group of objects featuring the Quebec flag (flags, cups, plates, keychains, ties, bottle openers, and so on), limiting his creative role to that of collector and organizer.

With Études préparatoires, a shift occurs. The recurrent motif, though inspired by the drawings of explosions found in superhero comic books, does not already exist in the found object. It is the artist who produces and reproduces it from one photograph to the next. It becomes a sort of signature that allows him to gather into one vast series heterogeneous images – although they have in common being black and white and drawn from books are dated, if not out of print. This time, the system is induced and not deduced. The artist improvises, becomes involved, makes his mark.

The colourful explosion may also be seen as a comment on the artist’s own work. First, he evokes the ideas of rupture and surprise, which, since the advent of modernity, have become an imperative. The injunction to bring out the unexpected is no longer avoidable, even if it means a burst of laughter. Here, Phaneuf uses it tautologically: in his work, the surprise is the very image of a surprise.

The star shape also refers to creation as desire for expansion, an aspect exploited by Phaneuf in most of his works. Explosion, sprawl, profusion, and sparkling are among his favourite subjects and forms. In his books (Phaneuf is also a writer) and installations, accumulation is his method. Hundreds of snapshots succeed each other in his book of poetry Fashionably Tales, whereas Téléthons de la Grande Surface is composed essentially of lists (“Le diagnostic: Le cancer, la fibrose kystique, le sida, des campagnes de sensibilisation, General Idea, Group Material, une dystrophie, les Cheerios en plaques, des Weetabix, le rhume, la grippe, la toux, la coqueluche de l’école . . .”2).

The explosion motif refers to art as the proliferating activity that it now is. Filling physical spaces, filling pages, and, ultimately filling the heads of readers and spectators – that is the function of today’s artist (whose interest has shifted from interiority to radical exteriority). The extravagant number of projects that Phaneuf has produced over the last five years (thirty!), the multiple roles that he plays (artist, author, curator, actor, critic), and his interest in projects beyond walls are all indications of his exuberance. He applies the “all-over” technique well beyond paintings – mimicking, among other things, the invasion induced by capitalism (industrialization, reproduction, the star system, media hyper-coverage, bombardment of new technologies).

In Études préparatoires, the coloured stars often appear in images presenting heroic male figures, such as a politician (Pierre Elliott Trudeau), hockey players, car racers, and conquerors of space. By enhaloing these stereotyped figures, the artist admits to a certain curiosity about these men whose goal in deploying their energy is to fire up the imagination of their contemporaries. If we were to force the issue, we might even see an extension of this interest in virile strength in the photographs of monumental architectural structures that the artist has chosen to highlight.

If Phaneuf had held to these categories of images, he would have limited the meaning and scope of his work and would not have reached the end point of his logic of excess. By integrating the explosion motif into images of foliage, Florida beaches, and Quebec winter landscapes, he explodes the system that he himself instituted. The spectator is thus led to experience the absurd. “The work of art,” wrote Camus, “is born of the intelligence’s refusal to reason the concrete. It marks the triumph of the carnal. It is lucid thought that provokes it, but in that very act that thought repudiates. It will not yield to the temptation of adding to what is described a deeper meaning that it knows to be illegitimate. The work of art embodies a drama of the intelligence.”3 Incapable of establishing logical connections, spectators must make a choice: either they turn away from this absurd artwork to find another, more comfortable one, or they follow the artist into this excess that requires them to become fully aware of the “confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.”4

The fact that Phaneuf, generally critical of the authenticity so sought after in art, physically invests himself in the drawing (we sense the presence of his hand) may be seen as an invitation to follow him. As we look closely at each image, we see the distinctive choices that he has made: revealing contours, magnifying a movement, underlining a junction, masking an element, creating a transparency.

In this abandonment to the pleasure of composition, Phaneuf sketches a poetics of space that cannot be dissociated from a poetics of time. For an explosion is also a strong temporal mark. In inducing suddenness in pages that are about the past, the artist creates sorts of anti-vanities in which a radical rejection of oblivion and death is expressed. His way of reuniting in a single series major events (conquest of space), notable events (plane crashes), minor events (hockey fights), and non-events (a forest) creates a dilation of time beyond the hierarchies habitual in history. This exploding time has nothing to do with eternity and expectation. It is, rather, one of a ferocious love of the real and a rejection of loss, even of what seems to have absolutely no value. In this alliance with time and with agitations of the world, in this taking account of the human measure, in this embrace of space, in this tireless and studious preparation, Phaneuf evidences a remarkable sensitivity to the absurdity of our lives, whether we are artists or not.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf, Téléthons de la Grande Surface (Montreal: Le Quartanier, 2008), 30.

3 Albert Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” in The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, trans. Justin O’Brien (New York: Vintage International, 1991), 97.

4 Ibid., 28.

Charles Guilbert writes prose, poetry, a journal, and critiques. He draws, sings, and makes videos. His works have been presented in France, Luxembourg, Mexico, Japan, and other countries. His work has been included, among other events, at the Biennale de Montréal (1998) and the Manif d’art (2005). In the fall of 2014, he presented ink drawings and a short video at Galerie B312 in Montreal.

Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf is an artist and author. Since 2006, his work has been presented in a number of artist-run centres, galleries, and museums in Quebec, including the Centre Clark, VU PHOTO, articule, the Musée régional de Rimouski, the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery, galerie antoine ertaskiran, and Optica. He has published three books of poetry with Éditions Le Quartanier, including Cavalcade en cyclorama (2013), written during an eight-day writing performance. In 2015, he presented the first version of Fins périples dans les vaisseaux du manège global, a literary show combining photography and poetry. He lives and works in Montreal.

Translated by Käthe Roth