[Fall 2017]

By Pierre Dessureault

The NFB’s Still Photography Division was created in 1941, as a Canadian government information agency under the direction of John Grierson. By 1985, when the small unit’s production, now a collection of photographs, became the core of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Division had produced some 250,000 images. Part of this rich heritage is examined in the exhibition The Official Picture – The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941–1971,1 curated by Carol Payne and Sandra Dyck for the Carleton University Art Gallery.2

In making their selection from this huge archive, the curators wanted to explore “how this agency imagined Canada and Canadian identity, what role photographs played in that imagining, and how the NFB’s photographic archive was – and continues to be – used.”3 They distanced the exhibition from an aestheticizing approach, positioning the images in a narrative in which they are social facts that provide examples of cultural practices during an era that was pivotal for the development of Canadian photography.

Grierson had a lasting influence on the output of the Division, the mission of which in the early years was to mobilize public opinion in the war effort by quenching Canadians’ thirst for information and keeping spirits up. Once peace was re-established, the Division was tasked with promoting an industrious nation, both domestically and internationally, and reflecting a sense of common values. In Grierson’s vocabulary, this was the role of propaganda, which was best conveyed by photo features.4

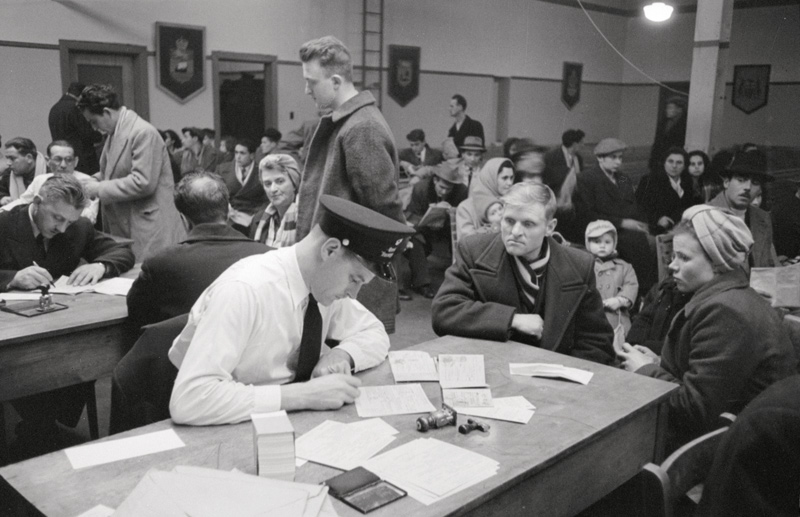

The images produced by the Division’s photographers were the raw material for these composite pieces. The subjects were numerous and typical, and the situations were representative of all regions of the country. The people in the pictures naturally play their proper roles with an agreed-upon theatricality in which each embodies either a particular social type or an exemplary model of citizenship. Even when we know their identity – for example, women working in a weapons plant whose activities we follow step by step – we know almost nothing about them. Props are carefully positioned to increase the veracity of the scene and reduce the portrayal to its simplest expression. The familiarity of the people and the situations make the event accessible to everyone.

For their didactic aim to be fulfilled, these unaffectedly realistic images had to be perfectly clear and immediately legible: the photographers worked with large-format cameras and almost always used bland, uniform backlighting to strengthen the natural look of indoor scenes. The composition highlights the main subject and sweeps all superfluous details out of frame. The photographer usually adopted a frontal point of view; this accentuates the scene’s neutrality and distances it so that the principal subject is pushed into the foreground.

Photo features were a collective undertaking in which the photographers were only the first actors in a chain of interventions. In their wake, writers built a scenario and wrote legends and accompanying texts, weaving a narrative that linked all parts of the piece in an organic, vivid relationship. The graphic designer imbued the narrative with a visual rhythm through the layout, reframing the photographs to fit harmoniously on the page and establishing a hierarchy among them: an emblematic image summarizing the topic was prominently placed to capture the reader’s attention and was surrounded with complementary images. The intentionality of these constructions of words, images, and graphic design did not belong to the photographers, who often remained anonymous; although they spoke with a single voice through their exceptionally high-quality photographic work, their vision was subordinate to the propagation of an institutional point of view that blended personal approaches together.

Whereas the 1940s and 1950s were the era of propaganda for the Division, the 1960s saw a shift in focus. The mandate – to be the official photography agency of the Canadian government – remained the same, but the interpretation changed, as did modes of distribution, contexts for presenting photographs produced, and, especially, the discourse that framed its production. The Centennial of Canadian Confederation, celebrated in 1967, brilliantly marked the Division’s new orientations with the publication of three commemorative books. Stones of History5 was a perfect match for the Division’s mandate. This study of the architecture of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa featured black-and-white and colour photographs of the interior by Chris Lund – the only in-house photographer still on the job – and exteriors by Malak.

The real break with the past was marked by the other two books, Canada: A Year of the Land6 and Call Them Canadians: A Photographic Point of View7. Canada: A Year of the Land featured colour photographs and an aesthetic interpretation of the landscape, represented in the exhibition by a series of images produced by the Division for the Tourism Bureau in which the tourist destinations, chosen for their emblematic value and the people they pictured, promoted the desired message. The shimmering colours enhance the descriptions – a perfect illustration of the how colour was commonly viewed at the time, as an advertising tool. The book offers a completely different approach to both landscape and colour. Here, the theme of landscape dominates and is envisaged as the basis of an identity. Formal, timeless beauty leaps off the page, and the qualities of the colours that structure the pictorial space are the images’ essential component. Making an impression wins out over depicting reality.

Call Them Canadians, as its title implies, portrays Canadian citizens. “The book deliberately refrains from identifying people by their geographic locale or ethnic origin for this is not a socioeconomic study or a statistical review. There is not even a record of where the photograph was taken. It does not matter. The photographic moment alone is supreme.”8 In other words, the image takes undisputed centre stage. The book, “conceived as a Canadian Family of Man,”9 fits photographs of Canadians from all over the country into a mosaic that, like its model, flattens out distinction and proposes a unified vision of the country.

Although Lorraine Monk, the orchestrator of these ambitious projects, deliberately distanced herself from the propagandist discourse of the photo feature, she remained true to the Division’s mandate in her presentation of a portrait of Canadians. It was the means used that changed. The photographs chosen were the work no longer of in-house photographers inured to the conventions of the institutional vision, but of a new generation of freelancers in step with the practices of the day. Although photographers such as Michael Semak, Michel Lambeth, Pierre Gaudard, John de Visser, John Max, and their colleagues highlighted their familiarity with their subjects, there was an air of spontaneity about their black-and-white snapshots; they embraced “the photographic moment” with a personal approach that put aesthetics and content on an equal footing. The linearity of the book strengthens the singularity of their images, reproduced on full pages and presented one after another in a play of reflections and references to a path along which readers can construct their own itinerary.

What changed just as radically in these publications was the nature of the accompanying texts and their degree of importance. They were poetic in nature. Their goal was no longer to overdetermine the images through dogmatic discourse, but to enwrap them in lyricism to open their way to the poetry that transfigures life. The images were thus ennobled by the words that described them. Legends that would inscribe the photographs’ content in a tangible reality and affirm the specificity of their origin were wiped away in favour of a vision of their universal draw as autonomous entities in the world of beauty. This creative recontextualization made the photographers and their sovereign vision the sole landmark for situating their pictures.

The recognition of photography, initiated in these publications, would continue with the the creation in 1966 of the Creative Photography Collection, which turned an image bank into a bona fide collection and the opening in 1967 of The Photo Gallery, the first gallery in Canada devoted entirely to photography. In the wake of these two significant advances in Canadian history of photography came the series of monographs titled Image, published between 1967 and 1971, each of which dealt with a different practice of the time: avant-garde art (7, 8, 9), auteur documentary (4, 10), collectives representative of regional practices (2, 6), and auteur monographs (1).10 Some of the essays introducing these books act as the inception of a discourse on photography in itself. One example is the introduction by Ronald Solomon, photography editor, presenting his choices for Image 6: “In his [the photographer’s] role as commentator he is becoming more and more conscious of the relation between his vision, the quality of his images and its effect upon his audience. There are in the analysis strong indications of a continuous struggle to make the message in the photograph clear and its meaning plain to the large and ever increasing audience for visual media.”11 This transition from institutional discourse conveyed through images to discourse on photography as a medium on its own set the course for the Division’s later activities.

As a conclusion, the exhibition offers a reflection, from a selected corpus, on how images have a life that is perpetuated in successive rereadings of them. Two projects, Project Naming and Views from the North, are repatriating into their communities of origin thousands of images produced by the Division in the North in the 1950s and 1960s, so that the people in them can be identified and the stories they evoke can be told. Through the use of oral history, these ethnographically important documents, which provide some detailed information on a world that was largely unknown at the time they were produced, are coming back to life and existing no longer through new eyes representative of the government in the South, but through the living memory of the community, which adds complexity to the narrative that they portray by returning depth to the image. The people in the pictures, previously frozen in a portrayal of a type of human being in a mute social theatre, come to life and become flesh-and-blood actors in a personal history and stakeholders in the communal destiny. The archives are thus revived by being put back into circulation in new contexts created by advances in research, and in the wake of advances in analysis methods, as much as by social uses that are made of them and the retrospective looks at them.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The exhibition was also presented at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa from January 23 to May 1, 2016, and at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston from August 27 to December 4, 2016.

3 Exhibition introductory wall panel.

4 John Grierson, “The Challenge of Peace” [1945], in Grierson on Documentary, ed. Forsyth Hardy (London: Faber and Faber, 1966), 328.

5 Chris Lund and Malak, Stones of History: Canada’s Houses of Parliament, essay by Stanley Cameron (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1967).

6 Lorraine Monk, Canada: A Year of the Land, essay by Jean Sarrazin (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1967).

7 Lorraine Monk, Call Them Canadians: A Photographic Point of View, poems by Miriam Waddington (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1968). See Payne, Official Picture, 155–62, for a detailed analysis of the major differences between Call Them Canadians and its French-language co-publication Ces visages qui sont un pays recueillis par les photographes du Canada, legends by Rina Lasnier (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1968).

8 Monk, Call Them Canadians.

9 Memorandum from Lorraine Monk to Grant McLean, August 19, 1963, quoted in Payne, Official Picture, 146.

10 For a detailed analysis of these productions, see Martha Langford, Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board (Edmonton: Hurtig, 1984), and “The Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography,” History of Photography 20, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 174–80.

11 Ronald Solomon, Introduction, Image 6 – A Review of Contemporary Photography in Canada, Ottawa, 1970, n.p.

Pierre Dessureault is an expert in Canadian and Quebec photography. As a curator, he has organized some fifty exhibitions, published catalogues, contributed to books, and written a number of articles on photography. Since his retirement, he has devoted himself to studying international photography in a historical perspective and, reviving his early interest in philosophy and aesthetics, to exploring in greater depth the theoretical approaches that have marked the history of the medium.