[Fall 2017]

By Érika Nimis

Three solo exhibitions1 (Katia Kameli, Délio Jasse, and Vasco Araújo) organized in London late in 2016 featured episodes from African and European history, particularly during the colonial period, in which the artists used “traces,”2 mainly photographic corpuses dating from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, updated via different media and devices. A number of contemporary artists in Africa and Europe have felt a similar need to look at history directly by drawing on archival images related to the most troubled periods (thanks, notably, to digital tools that make it easier to “dust off” these archives). In Africa, artists’ views of countries embroiled in a long and painful decolonization process, in some cases completed at the price of a war of independence followed by a civil war – as occurred in Algeria, Mozambique, and Angola – are particularly steeped in the “roman national”3 (“national novel”) that is omnipresent in museums, schools, media, and arts such as photography,4 as well as literature, music, and film.

The artists whose exhibitions I discuss here are from the “new generations” – those that did not directly experience colonization and the wars of decolonization and that are determined to leave the prison of colonial trauma (to use the term coined by historians Mohammed Harbi and Benjamin Stora5). They approach history through intimate experience. Individuals, and their faces and words, are essential, as the artists rely on private (family pictures, oral or written testimonials) and unpublished or marginal sources to give flesh and words to this period, which is still taboo in the official narratives of their respective countries. They want to probe what has been handed down to them, so that they can visually transcribe their own experience of the memory and history inherited from the colonial period. Their common desire is to calm memorial tensions on both the African side (where the official memory has become fissured) and the European side (where different communities of memory attempt to coexist6). The narrative dimension important to their works is formally conveyed by different devices, which I describe below.

In Le roman algérien7 (2015), a sixteen-minute video presented during the exhibition What Language Do You Speak Stranger? at The Mosaic Rooms,8 Katia Kameli asks Algerians about their complex relationship with history, taking as her point of departure the booth that the Azzoug family sets up daily, on a busy street in downtown Algiers, to sell items (stamps, coins, and postcards) to collectors. For thirty years, father and son have collected and sold, at modest prices, reproductions of postcards covering almost two centuries of history, mixing, in no particular order, in the manner of an “Algerian Atlas Mnémosyne”9 (expression borrowed from the artist), genre scenes and colonial buildings, advertising, and portraits of important political figures.

This mosaic of postcards and reproductions of archival photographs refers fragmentarily to the period of French colonization, then to that of Algeria’s independence, achieved during the cold war. In the off-screen testimonials that form the soundtrack of the video (which benefits, I should note, from understated, effective editing), father and son, some customers, and intellectuals analyze the complex, ambiguous relationships (in some cases going as far as schizophrenic) that Algerians have with their own history, and with the images linked to them. According to one speaker, “The [post]card is the art teacher that tells a story . . . in a country in which everything that is art and history belongs to the state.” And, historian Daho Djerbal adds, “Figures have been excluded from the textbooks.” Thus, the booth allows for “an encounter with a representation of figurative history.” Indeed, just after the war of independence fought against France, the watchword was to wipe the slate clean: to begin the “national novel” with the “revolution” that had led the “people” to the country’s liberation and to erase as many traces of colonial domination as possible, in sites of both power and knowledge. Whence the necessity for private initiatives, such as this booth in the heart of Algiers, to fill certain “holes in history.” Not all of them, though, as a speaker in the film reminds us: the “black decade,” the Algerian civil war of the 1990s and 2000s, is not portrayed anywhere in Algeria, not even in the Atlas Mnémosyne whose chronological timeline extends back to the 1980s. The unique space of the Azzougs’ booth, open to everyone who visits (as is the Web), nevertheless responds to a vital quest, that of defining the contemporary Algerian identity that is the product of a complex history on both shores of the Mediterranean.

Délio Jasse also belongs to two shores – these ones separated by the Atlantic Ocean – whose memories he tries to reconcile. Born in Luanda in 1980, he left Angola, at the time being ravaged by a long civil war, in 1998. When he arrived in Portugal, he experienced the solitude of the undocumented immigrant. Limited in his movements for several years, he took refuge in a family photo album, in which he sought his past, and in the darkroom, where he learned about old monochrome printing processes such as cyanotype10 and platinotype.11 He also began to haunt Lisbon flea markets for bargains, collecting “abandoned” photographs and papers (of which he called himself an archivist). Beyond his quest for identity, memory was to take a central place in his artistic approach. His studio became his refuge; his images and documents, gleaned from flea markets and yard sales, his creative materials. In 2010, he returned to Angola for the first time, after twelve years of exile. His current work took shape from there.

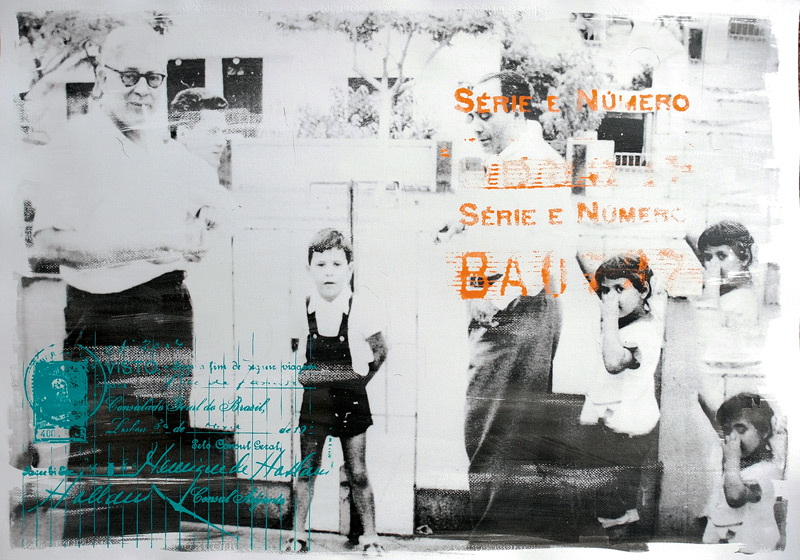

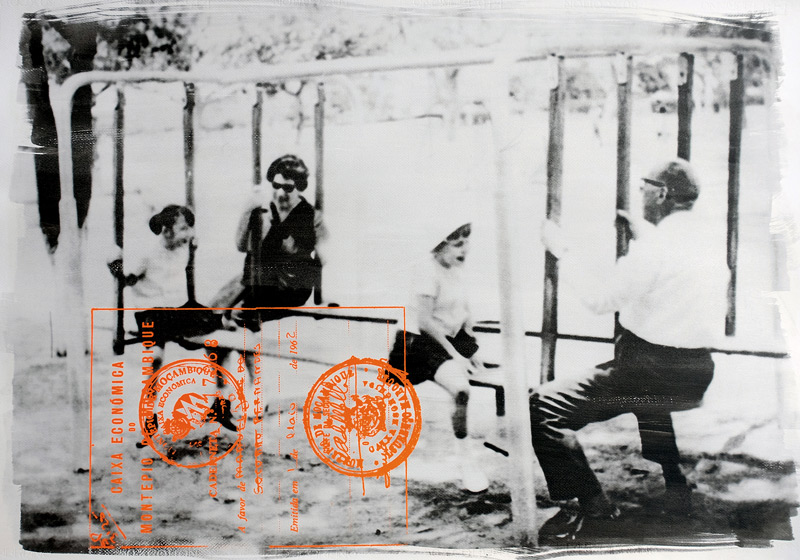

His latest series, displayed in late 2016 at Tiwani Contemporary,12 has a single legend: The Lost Chapter: Nampula, 1963. The images in this series are taken from his own collection of found images: hundreds of photographs kept in boxes, many of which are from a Portuguese family (whose identity is secret) that moved to Nampula, Mozambique, in the 1960s. After working for months on these archives brought back from the void, Jasse appropriated fragments from the past of this family of retornados13 (repatriated people), combining them, through an overprinting process, with administrative documents (passport pages) and personal documents (handwritten letters), in order to shed light, layer by layer, on the unique and yet universal story of this family. By intermingling these anonymous portraits, places, and documents, vestiges of long-gone lives, via the figure of the palimpsest, Jasse seeks to re-create all perceptible dimensions of a story, his own, through that of this family, in a spirit of total tranquillity.14

In another register, but still with the desire to address unspoken history, the Portuguese artist Vasco Araújo, whose work was exhibited at the Musée de Joliette in 2011, had a provocative show called Decolonial Desire in an London venue, Autograph ABP, that for more than twenty-five years has been militating for recognition of black communities.15 This exhibition space has presented shows such as Black Chronicles: Photographic Portraits 1862–1948, also displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, featuring portraits of people of African and Asian descent, bearing witness to the long-time presence of these communities in the United Kingdom, a country with an imperial history as fraught as Portugal’s. The research program underway at Autograph ABP, Missing Chapter,16 emphasizes the diversity of contributions by these communities to British society. Decolonial Desire included a number of Araújo’s works that fearlessly peel away the notion of exoticism in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Portuguese colonial imagination. Among the installations and videos presented, I will spend time on a grouping of four composite sculptures from the Botânica series (2012–14): tables made of rare wood serving as display bases for a selection, at first glance incongruous, of framed photographs straight out of the “colonial library” (to use philosopher V.-Y. Mudimbe’s term). To “stage” this colonial world, to place it in front of visitors’ gaze, fully vertical, Araújo literally erected these tables, confronting viewers with the sad spectacle of human exhibitions produced in Europe at or ignorance regarding its colonial past (and its repercussions in the present day) and invites us to critically rethink that past. Each in its own way, the three works discussed here bring to light a corpus of photographs that have been forgotten or made invisible in “national narratives” of countries whose colonial past remains taboo – a missing or lost chapter. Appropriated through various media (video, photography, or sculpture), these photographs thus help to overcome the silences of official history, even to repair the traumas of memory, by offering contemporary viewers “traces” of places, events, and – especially – faces that decompartmentalize and liberate history.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The term used by one of the artists reviewed in this article, Délio Jasse.

3 Historian Mohammed Harbi often alludes to the “roman national” in his writings about the official history distilled by the Front de Libération Nationale in Algeria.

4 Such as the work of Algerian photographer Mohamed Kouaci, evoked in a video installation by Zineb Sedira, Gardiennes d’images (2010). Kouaci died an unknown in 1996, even though his work was found throughout Algeria – on stamps, on murals, and among the reproductions presented in the photo kiosk in Katia Kameli’s work Le roman algérien.

5 Mohammed Harbi and Benjamin Stora, ed., La guerre d’Algérie, 1954-2004. La fin de l’amnésie (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2004) p. 13.

6 See Djemaa Maazouzi, Le Partage des mémoires. La guerre d’Algérie en littérature, au cinéma et sur le web (Paris: Classiques Garnier, “Littérature, histoire, politique” imprint, 2015).

7 This video, the first chapter of Roman algérien, was produced for the exhibition Made in Algeria, about the history of Algeria through cartography, at MuCEM in Marseille.

8 This London cultural and exhibition space is devoted to promoting “contemporary culture from the Arab world.”

9 After the art historian Aby Warburg, who had compiled an important corpus of images in the 1920s that he called Atlas Mnémosyne (after his library). See Teresa Castro, “Atlas: pour une histoire des images ‘au travail’,” Perspective : actualité en histoire de l’art 1 (2013), put online December 30, 2014, accessed June 1, 2017, http://perspective.revues.org/1964.

10 Cyanotype is an old negative monochrome process that produces a cyan-blue photographic print.

11 Platinotype is a monochrome process based on the photosensitivity of iron and platinum salts.

12 Opened in London in 2011, Tiwani Contemporary (tiwani means “it belongs to us” or “it is ours” in the Yoruba language) is a gallery that highlights the work of emerging and established artists of Africa and the African diaspora.

13 The retornados are to Portugal what the pieds-noirs are to France: in 1974–75, following the fall of the Salazarist dictatorship in Portugal, which led to a dismantlement of its colonial empire, these settler families who had been living in Africa, some of them for several generations, were “repatriated” en masse to their homeland.

14 See Lloyd Pollak, “The Endless Absence of Delio Jasse”, Artthrob, November 2014, accessed June 1, 2017, http://www.artthrob.co.za/Reviews/Lloyd_Pollak_reviews_The_Endless_Absence_of_Delio_Jasse_by_Delio_Jasse_at_SMAC_ART_GALLERY_CAPE_TOWN.aspx.

15 Opened in London in 1991, Autograph ABP (previously the Association of Black Photographers) is an international non-profit art agency. Mark Sealy, its director, was a guest curator at Ryerson Image Centre in 2013, presenting the results of his research on the archives of the Black Star agency in New York.

16 See the program’s page, accessed June 1, 2017, http://autograph-abp.co.uk/archive/the-missing-chapter.

Érika Nimis is a photographer (former student at the photography school in Arles, France), Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.